This post was first published in 2013.

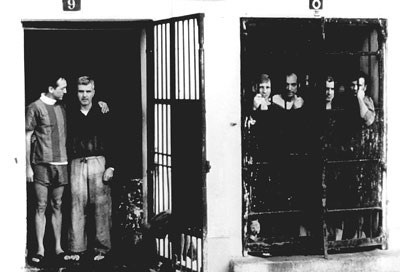

Admiral James Stockdale with fellow prisoners of war in the North Vietnamese prison known as the Hanoi Hilton

Over twenty-five years ago, I first encountered the writings of Admiral James Stockdale (second from left in the above picture). They were writings about philosophy and life as a prisoner of war.

Stockdale was the highest-ranking US officer imprisoned by the North Vietnamese. His story is one of strength and resilience in the face of torture. His attitude and behavior, during the eight years that he was in the Hanoi Hilton prison, provided the leadership that made it possible for other POWs to survive the ordeal.

Jim Collins did the world a favor by bringing Admiral Stockdale's story to a wider audience. In his book, Good To Great, Collins presents the leadership principle, The Stockdale Paradox.

The Stockdale Paradox is two practices, that when joined together, provide a strength of character that is hard to match. Collins describes it as the capacity to,

"Retain unwavering faith that you can and will prevail in the end, regardless of the difficulties, AND AT THE SAME TIME have the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be."

This is a way that people can maintain a clear connection to reality, even in the midst of the most difficult of circumstances.

Loss of Hope

Hope and optimism have always been part of the public face of leadership. Yet, I know many people in positions of leadership who are filled with doubt, disillusionment and are lacking in hope for the future.

One of the reasons is the effect that living in a world of images and hyperreality, in The Spectacle of the Real, has upon us. In this culture, our sense of self, self-perception, and awareness is established by our outward appearance. This is more than whether we are young, handsome, or pretty. It is seen in the products we buy, the causes we join, the celebrity figures we follow, and the way we spend our off-time.

A friend recently recommended to me a book by a popular business consultant. He did so because he felt that the author and I were addressing leadership issues in the contemporary world in very similar ways. I will not name her or her book out of respect for her past work which I find innovative and useful. This book, however, is a personal cri de coeur. It crosses a boundary of expression that is not simply an author demonstrating her change of mind, but rather raises questions about the perspective that she has presented to her readers for the past two decades. She reveals her own loss of faith in the ability of people to change the world. Is this a way of grabbing her audience's attention, or is she really a person who has lost hope?

My reading of the book left me with the uneasy feeling that her loss of hope has led her, not to self-reflection, but to blame the public for not recognizing the genius of her ideas.

Here's how she frames her loss of hope.

Many of us – certainly I’d describe myself in these terms – were anxiously engaged in “the ceremony of innocence.” We didn’t think we were innocents, but we were. We thought we could change the world. We even believed that, with sufficient will and passion, we could “create a world,” one that embodied our aspirations for justice, equality, opportunity, peace ... This vision, this hope, this possibility motivated me for most of my life. It still occasionally seduces me into contemplating what might be the next project, the next collaboration, the next big idea that could turn this world around. But I’m learning to resist the temptation.

This is not a book that contemplates what we might do next, what we’ve learned from all our efforts, where we might put our energy and experience in order to create positive change. I no longer believe that we can save the world. Powerful, life-destroying dynamics have been set in motion that cannot be stopped. We’re on a disastrous course with each other and with the planet. We’ve lost track of our best human qualities and forgotten the real source of satisfaction, meaning and joy. ...

But now, for many reasons, hope is hard to find and the good people who have created successful projects and built effective non-government organizations (NGOs) are exhausted and demoralized. They keep doing their work, but it’s now a constant struggle. They struggle for funds, they struggle with inept, corrupt bureaucracy, they struggle with the loss of community and the rise of self-interest, they struggle with the indifference of the newly affluent. The dream of a new nation of possibility, equality, and justice has fallen victim to the self-serving behaviors of those with power.

Yet I have not set out to write a book that increases our despair. Quite the contrary. My intention is that we do our work with greater resolve and energy, with more delight and confidence, even as we understand that it won’t turn the world around. Our work is essential; we just have to hold it differently. ...

How do we find this deep confidence that, independent of results, our work is the right work for us to be doing? How do we give up needing hope to be our primary motivator? How do we replace hope of creating change with confidence that we’re doing the right work?

Hope is such a dangerous source of motivation. It’s an ambush, because what lies in wait is hope’s ever-present companion, fear: the fear of failing, the despair of disappointment, the bitterness and exhaustion that can overtake us when our best, most promising efforts are rebuked, undone, ignored, destroyed. As someone commented, “Expectation is pre-meditated disappointment.”

The author, with respect to her, is a victim of The Spectacle of the Real. She considers herself one of the experts who have the answers for solving the world's problems. She is so confident about the work she and her colleagues have been engaged in, that she cannot imagine, how on earth the world has not embraced the relevancy of their message. Her loss of hope is essentially a loss of faith in herself. She is a victim of her own celebrity and the followers who tell leaders just how important they are. There is more that I could say in my critique of her book, but that is not, ultimately, my intention here. She is a reference point for what follows.

The Stockdale Paradox

To stay connected to reality, and remain hopeful about the future, requires resilience and circumspection. Hope must be held within the context of the way the world actually is. Not the way we'd wish it would be. In other words, if we can embrace reality and maintain hope, then we can find a way to achieve our life and work goals, rather than abandon them.

In his book Good To Great, Jim Collins describes his first encounter with Admiral Stockdale as they walked across the campus of Stanford University.

"I never lost faith in the end of the story ... I never doubted not only that I would get out, but also that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience into the defining event of my life, which in retrospect, I would not trade."

Collins, after few minutes of reflection asked,

"Who didn't make it out?"

"Oh, that's easy," he said. "The optimists."

"The optimists? I don't understand," I said, now completely confused, given what he's said a hundred meters earlier.

"The optimists. Oh, they were the ones who said, 'We're going to be out by Christmas.' And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they'd say, 'We're going to be out by Easter.' And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart."

Another long pause, and more walking. Then he turned to me and said,

"This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end - which you can never afford to lose - with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be."

To this day, I carry a mental image of Stockdale admonishing the optimists, "We're not getting out by Christmas, deal with it."

Reading Stockdale's account of his imprisonment, In Love and War: The story of a family's ordeal and sacrifice during the Vietnam years (co-written with his wife, Sybil, a national leader of POW wives, who brought public attention to the plight of POWs and their families), provides the backstory that illustrates the principles he described to Jim Collins.

I want to use the Stockdale story as a mirror to reveal that the unnamed author of lost hope is one of Stockdale's optimists. She lives with the resignation that "I no longer believe that we can save the world." Her statement is not a judgment about the world, but, in truth, about herself. She believed, naively, in my estimation, that the power of her ideas, and her approach to leading are self-evidently the way the world must go. All we must do is follow her lead. Her disillusionment came in seeing that "Powerful, life-destroying dynamics have been set in motion that cannot be stopped."

Sadly, and most importantly, she does not believe that she and her colleagues will prevail in the end. Instead, "that we do our work with greater resolve and energy, with more delight and confidence, even as we understand that it won’t turn the world around. Our work is essential; we just have to hold it differently."

This is an odd denial of reality and loss of vision for how we can adapt to the realities of the world as it exists. On the one hand, she believes that the world cannot be saved. Yet on the other, she still believes that her work is essential. What is missing is reflection, circumspection, and positive self-criticism. She needs the capacity to look at her own reality, at the brutal facts of her situation, assess and recognize her own failings or limitations, and then to understand how to work with greater resolve and energy, with more delight and confidence, to prevail in the end. Her problem is not her ideas for change, but a lack of grounding in reality.

The line between idealism and defeatism is thin. What this unnamed author of lost hope needs is the inner strength of resilience to face the obstacles that stand in the way of changing the world. Embedded within her philosophy is a deterministic perspective that sees the world as a system of emergent forces that are outside of our control. If she is correct, then her loss of hope makes sense, and we should join her. If, on the other hand, there is the freedom to affect these impersonal forces, to foster change in the world that makes a difference, then her loss of hope is not grounded in reality, but in her own fear or loss of faith in herself.

To embrace reality in this way requires a capacity for self-learning that is more than philosophical, but at the practical level of character development.

Hope in the Midst of Torture

North Vietnamese Rope Torture

In a speech that Stockdale gave following his return, he speaks about the US military's Code of Conduct which was the ground upon which POWs lived under torture.

"I am not aware that any POW was able, in the face of severe punishment and torture to adhere strictly to name, rank, and serial number, as the heroes always did in the old-fashioned war movies, but I saw a lot of Americans do better. I saw men scoff at the threats and return to torture ten and fifteen times. I saw men perform in ways no one would have ever thought to put in a movie, and because they did perform that way, we were able to establish communication, organization, a chain of command and an effective combat unit. ...

Unless you have been there, it is difficult to imagine the grievous insult to the spirit that comes from breaking under torture and saying something the torturer wants you to say. ... But I and many others were tortured in ropes ... The reason it was important to take torture ... was to establish the credibility of our defiance - for personal credibility ...

In short, what I am saying is that we communicated. Most of the time most of us knew what was happening to those Americans around us. POWs risked military interrogation, pain, and public humiliation to stay in touch with each other, to maintain group integrity, to retain combat effectiveness.

We built a successful military organization and in doing so created a counterculture. It was a society of intense loyalty - loyalty of men one to another ..."

To live in this kind of life situation requires circumspection paired with an indomitable commitment to prevail over the brutal facts. This is not egotism plus stubbornness. Rather, it is self-awareness and resilience.

In his memoir, following a torture session where he surprised his torturers with an outburst of anger, Stockdale writes,

"Anyway, I'd committed myself to another course now. Live and learn, live and learn. The rules of this ball game would change as we went along. But for now, I was spinning the web, and I like it better on this side of the fence. Time would tell."

This is the attitude of prevailing.

Hope in Hard Times

Many people I know have experienced hard times. They have lost their businesses to economic collapse. They have lost children to suicide or drug and alcohol abuse. They have seen their marriages end, or lose their spouses to cancer or other diseases. These people have every reason to have lost hope in the future. It is out of these relationships that I developed my Impact Day program. It is designed for people, groups, organizations, and communities who are in transition.

What I've learned from these friends and colleagues, as well as from my own experience of change, is that hope is not blind. Hoping against hope is not hope. It is the loss of hope.

Hope is visionary. It is something we can see, something we can imagine that is worth holding to, worth sacrificing for to gain a greater good in the future. In the case of Admiral Stockdale, he could see making it through, and going home. What does the unnamed author of lost hope see? Hard work and commitment without hope of success.

Hope that is Real

Hope - to believe in a better future - in the midst of an embrace of reality - confronting the brutal facts - requires us to live in the real world. Real as in the opposite of fake.

Umberto Eco wrote in his Travels in Hyperreality,

"... the American imagination demands the real thing and, to attain it, must fabricate the absolute fake. ... the frantic desire for the Almost Real arises only as a neurotic reaction to the vacuum of memories; the Absolute Fake is offspring of the unhappy awareness of a present without depth."

The present moment without depth is a future without hope.

It is the loss of the past as a living reality, the loss of reality as a context for understanding, and, the loss of an embodied presence that gives a clear sense of who we are.

The hyperreal present is one without a past, a future, or hope.

Admiral Stockdale's POW war experience is analogous to our present culture of simulation and hyperreality. His captors created a fake world of isolation built around the false charge of criminality. The entire context of the prison was intended to break down the body in order to reach the mind and spirit. Reach the mind with doubt. Reach the heart with lost hope.

It was a game of propaganda. The intended audience for the fruits of torture was the American public, who would view this artificial hyperreality through the screens of televised news and their morning newspapers. The aim of the North Vietnamese was to create a hyperreality where the POWs looked like they were healthy and well-cared for, and had come to see the rightness of the North Vietnamese Communist cause. In effect, the war on the minds of the POWs was also a war on the minds and hearts of Americans in their homes across the country.

The Spectacle of the Real is a similar form of propaganda. Its methods are not physical torture. Its aim is the same. Isolate the individual into a present that has no past, nor future. This is a culture of alienation and lost hope. The Spectacle of the Real is an emotional vacuum that creates a longing for the real that can only be met through the emotional attachment to consumer products, celebrity entertainers, politicians, and, the 24/7 broadcast of opinions and advice by authorized experts. This is not an artificial reality, but a fake one, an unreal one that seeks to end individual thought and initiative.

One could describe this system of the spectacular in the words of the unnamed author of lost hope,

"Powerful, life-destroying dynamics have been set in motion that cannot be stopped. We’re on a disastrous course with each other and with the planet. We’ve lost track of our best human qualities and forgotten the real source of satisfaction, meaning, and joy."

Admiral Stockdale challenged a similar system in the Hanoi Hilton prison by creating a communication system that connected the POWs together. It was essential to their survival and their ability to resist the propaganda efforts of the North Vietnamese.

At one point during the POWs' resistance to being used for propaganda, Stockdale issued a general order not to volunteer for a bomb-debris cleanup in Hanoi. He writes in his memoir,

"... it was a trap - that for every prisoner, every shovel, there would be two cameramen snapping propaganda shots continually, and there we would be in the world press: 'American prisoners of war go to the aid of North Vietnamese patriots as Yank bombs rain on the city of Hanoi.' ... we made up another general order ... 'No repent; no repay; do not work in town.'"

The result of this defiance was that Stockdale was handcuffed in manacles, both feet and arms, and placed outside in an open courtyard exposed to the South East Asian sun. After three days, they came to take him to interrogation. He writes,

"I sensed I was going over toward Heartbreak (an isolated section of the prison), and my anxiety was high enough, with the cuffs still at full ratchet, that I called out my name: 'Stockdale, heading for Heartbreak!' In the midst of the noon-hour quiet, I knew some prisoner would pick it up. Position reports become an obsession when you realize how close you are to permanent isolation or even death."

Hope that is real amounts to a belief in one's capacity for adaptation and resilience. In our culture of hyperreality, the loss of hope is the loss of belief that one can prevail. This loss at the inner core of life requires us to create change in ourselves that builds character for a face-to-face confrontation with reality.

Ultimately, what I've learned, and Admiral Stockdale's story confirms it, is that prevailing in the face of the brutal facts cannot be done alone. We need others in our lives who believe in us so that we may believe in ourselves.

The reason I did not name the unnamed author of lost hope is to not isolate her any more emotionally than she already is. For to lose hope is to accept emotional isolation.

Finally, how do we have hope that is real? Three suggestions.

Follow The Stockdale Paradox.

Be absolutely convinced that you will prevail in the end, and at the same time, face up to and deal with the brutal facts of reality. The more you practice them, the greater confidence you have to stand on your own and be less subject to the hyperreality of modern-day consumer and political propaganda.

Establish relationships where Admiral Stockdale's two principles live.

We need people in our lives who believe in us. We need to believe in ourselves, but also in others as well. Where those relationships are strong, we can face the brutal facts of our world, with resilience and hope. These relationships require honesty, transparency, integrity, and mutual caring.

Learn to see how hyperreality is a fake reality.

A central point of this series – Reclaiming the Real -is to recover a belief that we can make a difference that matters. It is so people like the unnamed author of lost hope, the men who shared prison life with Admiral Stockdale, and the people you and I live and work with every day, may not lose hope, and find ways to live lives of meaning and impact.

May it be so for us all.

Okay. I see where you are going with this. Sorry if I misunderstood.

Stockdale’s story is unique partly for his conduct as the highest ranking officer imprisoned by the North Vietnamese. He had the responsibility of rank to lead his men. More so his story is noteworthy because his intentional application of philosophical principles. Here is an audio recreation of a speech that was also published as a pamphlet where he talks about these principles. https://youtu.be/pmA_Rn-R2y0

In the context of our discussion, I think there is a distinction to be made between duty and responsibility. Duty has the sense of something that I must do. Responsibility is something that I do because I am accountable for my actions and the outcome of my actions. Who am I accountable to? The people to whom I am responsible for and who are responsible to me.

Stockdale clearly felt responsible for each man under his authority as highest ranking officer in the prison. Here’s the Medal of Honor video where he describes his actions while in prison. https://youtu.be/Pc_6GDWl0s4

As a leadership guy, I see Stockdale not only as an example of what organizational leaders should be like, but stands in contrast to what leadership has become in our time. Your use of the idea of duty and the detachment of reward from the fulfillment of duty has some merit in our current context where corruption is a real problem of global proportions. However, detachment on a personal level has dire consequences on a social level. To fulfill duty as to some, let’s say, minimal fulfillment of the letter of the law would ultimately isolate every individual from one another to preserve one’s detachment. In a political prison, this not only affects the other inmates, but the nation as a whole. This is why I see Eastern philosophical detachment as idealistic and ultimately self-serving. Stockdale was prepared to die to preserve the lives of the men under his command. This ancient philosophical principle is found both in Stoic philosophy and biblical faith. And today is only found in people who do not carry the title of leader in organizations or public life. And with people who value the study of philosophy or have a biblical faith, this not about what believe, but what we do with our beliefs.

There is a parallelism between Stockdale and Alexandr Solzhenitsyn. Both were political prisoners, both suffered unjustly, both wrote about their experiences in service to those who suffered with them. I encountered the writings of both these men early in my career, forty years ago. As I turned from traditional ministry to leadership work, their influence remain central in my thinking about leaders. When Jim Collins came out with his construction called The Stockdale Paradox, an application for Stockdale’s example became available to many others. Here is Jim Collins speaking about his encounter with Admiral Stockdale. https://youtu.be/GvWWO7F9kQY

There is more to say, for another time.

reading this I thought of the Bhagavad Gita, hard to explain in a comments section, but to me it captures Stockdale's stoic approach. Accept the current reality, do what you can to change your reality and continue to do so, but still accept the facts of your current reality, almost an iterative process.

The last line of the Gita, nor be attached to inaction, is very important in this context.

Would love to hear your thoughts on this.

You have a right to perform your prescribed duties, but you are not entitled to the fruits of your actions. Never consider yourself to be the cause of the results of your activities, nor be attached to inaction.

Do your duty, but do not concern yourself with the results. We have the right to do our duty, but the results are not dependent only upon our efforts. A number of factors come into play in determining the results