Is Embodiment Our Common Thread?

How two conferences on embodiment point to a growing conversation between religion and science.

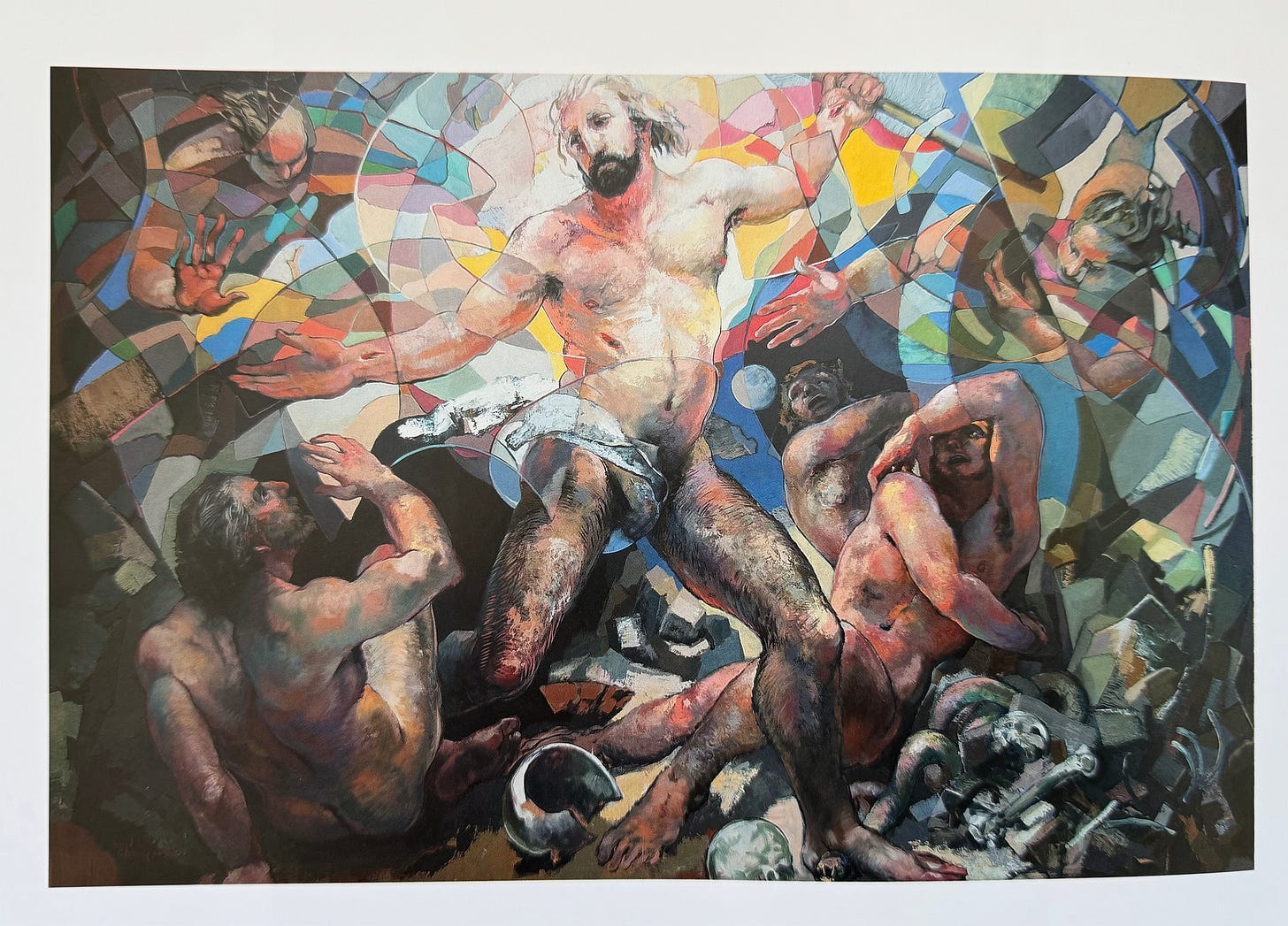

Angel at the Crucifixion - 1986

Edward Knippers

The Embodiment Question

This fall I attended two conferences where the idea of "embodiment” was central to the presentations. My experience at these events showed me that whatever you perceive as relevant or truthful is incomplete or partial. In other words, there are people thinking similar things that have no idea that there are others who are thinking similar things in a totally different context.

Embodied Faith

The first conference was entitled “Embodied Faith and the Art of Edward Knippers” held at the Charlotte campus of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.

At his website, Knippers presents his perspective on embodiment.

THE RESURRECTION OF THE BODY

The human body is at the center of my artistic imagination because the body is an essential element in the Christian doctrines of Creation, Incarnation, and Resurrection.

Disembodiment is not an option for the Christian. Christ places His Body and His Blood at the heart of our faith in Him. Our faith comes to naught if the Incarnation was not accomplished in actual time and space – if God did not send His Son to us in a real body with real blood.

Heresy results when we try to minimize the presence or preeminence of the body and the blood. Yet even believers have become comfortable with our age as it tries to disembody reality. Physicality is messy; it is demanding and always a challenge to control. In the name of progress, our communication is increasingly becoming a disembodied voice on the line or we listen to a virtual image on a screen. We move human interaction, even consciousness, from the real into a virtual realm. When we must deal with the physicality of the real world, it is increasingly uncomfortable.

The response to this discomfort for the physical world can be at least two fold. When it come to our bodies, we can resort to worshipping the physical creation as seen in contemporary sexual idolatry, including pornography and other sexual exploitation. When it comes to nature we can also feel a need to worship as is seen in the resurgence of pagan creation-centered religions. A second response is a resort to a kind of gnosticism, prudishly rejecting the physical creation’s importance and disdaining as evil what God Himself called “good.” Neither worship of the created order nor Gnosticism is a Christian response, especially when it comes to our bodies.

The body (both Christ’s and ours) is a mystery. Our physical being is not to be worshipped or disregarded. His is to be both worshipped and glorified. As orthodox Christians we insist on the bodily resurrection for both Christ (“…if Christ be not risen…your faith is also vain.” Corinthians 15:14) and, just as scandalously, for ourselves (“…he which raised up the Lord Jesus shall raise up us also by Jesus…” II Corinthians 4:14).We Christians believe that God paid the ultimate price for our redemption. That would not be true if He had given us only His mind (and thus been merely a great teacher), or only His healing (a great physician), or even only His love (a compassionate friend). Without His body broken for us, His sacrifice would be incomplete and we would be lost. For without the broken body there can be no redemptive resurrection.

The body for Edward Knippers is not a social or intellectual construct. It is our connection to reality. Whether or not you accept his biblical/theological perspective, the question of embodiment is emerging as a bridge between the secular and sacred.

The Future of Humanity is Embodied

The second conference was The Future of Humanity hosted by Iain McGilchrist held at The Royal Institution in London.

McGilchrist in The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World writes,

The nature of everyday perception, although we would not normally call it creative, shares something with the work of the imagination we recognize in the poet or other artist. This may sound odd, but it has to do with the manner in which this experimental world is brought into being for each one of us. That coming into being inevitably depends, even if only in a routine fashion, on what we know, what we already have in memory, and can bring to the process. …

The whole experiential world is constantly being created afresh. When we ‘perceive’ the world, we are neither passively receiving ‘data’ from the ‘environment’, as a camera or computer would; nor, on the other hand, simply projecting the contents of our mind on a screen.

Our current perceptions are governed by past perceptions and preconceptions; yet these two are always influenced reciprocally, if more weakly, by the new perception, the new experience. Much of what goes on seems to us pretty humdrum, largely the confirmation of our current perception (and conception) of the world. But even that is unbelievably complex and rich, and is born of embodied interaction. Clearly what we see depends on the whole context - where we are, with whom and why we are there, the mood we are in, and so on - and also on what our motivations are … There is no such thing as perception without such ramifications, because we are not just creating a Cartesian representation of the world, but are involved in the process of the experiential world coming into being. “

This embodied interaction takes place within a vast environment of life that cannot be contained within the structures of institutions or ideologies. It can be understood.

The Common Thread

The common thread is knowledge gained through sensory experience. When I was in seminary, almost 50 years ago, the measure of Christianity’s truth claims were captured in a philosophical idea called inerrancy. It is the claim that everything in the Bible is literally true, and therefore is the basis for believing that Christianity is true. The spectacle that surrounded this debate came to be called The Battle for the Bible centered around claims that the Bible represents absolute truth therefore could be trusted to be without error. The alternative perspective by other segments of the church viewed the Bible as an infallible source of truth for a life of faith The Bible is true in all that it affirms about Jesus, his ministry, death and resurrection, and the faith given to the church. It is true within the context of the story of the Christian faith.

The difference between these two claims of biblical truth is the difference between arguments from a theoretical system and ones from observations from experience. My theology classes used a theological philosophic overlay called a systematic theology as the guide for interpreting the text of the Bible. In my biblical studies classes, the text of Bible was examined from the soci-cultural, historical context of each of the books. Granted, this is still a systematic approach seeking to understand what the original recipients of the Bible understood. The challenge was to let the text speak for itself. and then, interpret it for contemporary readers.

A half century ago truth was treated as a thing or a collection of things that could gathered into a belief system, whether religious or scientific. However, times have changed and a very different understanding of truth is emerging. Today, truth is increasingly seen as an environment that we are constantly interacting with. It maybe most easily summed up as saying the Reality is Truth/Truth is Reality. In saying this, I am also saying that Reality is not a thing either. It is not a perception, but rather the context of our experience. The implication is that a lie isn’t just a false statement based on a philosophic governing rule, but rather a denial of reality. From this viewpoint, I came to develop The Spectacle of the Real perspective.

Truth is not a thing but a way of being or living.

The institutional structures of the world are not true in themselves.

They are but vehicles for truth to be discovered as an embodied experience.

It was for this reason that seeing my former seminary hosting a conference on embodiment was such a welcomed surprise. I realized that the phenomenological turn of the Twentieth Century was finding relevance in new arenas of discovery.

Forty years ago, in a bookstore in Atlanta, I discovered Michael Polanyi’s Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. He said things that made sense to me. It was the first time that I encountered a perspective that gave precedence to experience. Polanyi recognized that our bodies serve as a conduit for learning from experience. This knowledge he calls tacit. In his short book, The Tacit Dimension, he writes.

I shall reconsider human knowledge by starting from the fact that we can know more than we can tell. This fact seems obvious enough; but it is not easy to say exactly what it means. Take an example. We know a person’s face, and can recognize it among a thousand, indeed among a million. Yet we usually cannot tell how we recognize a face we know. So most of this knowledge cannot be put into words. …

When you are dealing with the whole of a person’s life, the rational mind is only part of that situation. Polanyi’s perspective made sense because so much of my work as young minister serving in an urban community did not lend itself to analytical reasoning.

Iain McGilchrist has described this reality in his work as a neuroscientist as the the asymmetrical hemispheric structure of the human brain. He writes, in The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking off the World,

One ground for believing that we might agree in our experience is the fact that we share our embodied nature - which even analytic minds, however much they may dream of being brains in vats, cannot escape. As Lakoff & Johnson make clear, metaphor is not an embellishment of thought, but its very ground.

Iain McGilchrist, The MatterWith Things, p578.

The common thread is knowledge gained through sensory experience. It means that both the truth that we gather from the spiritual experience of religion and the phenomenological experience of science speaks to a reality that is whole and complete in itself. Even this truth does not automatically mean contemporary religious and scientific perspectives are compatible or cohere. Instead, it suggest that how we talk with one another goes beyond biblical and philosophical propositions.

As a result, the question before us is how do we live an embodied life of both faith and discovery.

Let me explain.

The Case for Embodied Consciousness

From my experience and study, I believe that the link between religion and science is understanding the nature of consciousness. McGilchrist writes,

When we speak of consciousness, what are we talking about? The word literally means ‘knowing with’ … it is therefore an essence, not a thing, but a betweenness. …

When I use the word ‘consciousness’, I refer very broadly to all that we might call ‘the experiential’. This covers all the activities that go on, for each of us, as we say, unconsciously and preconsciously, as well as consciously; but could not go on without what is conventionally referred to as subjectivity, or inwardness, of some kind.’

Iain McGilchrist, The Matter With Things, p. 1039.

The spiritual experience of religious faith has a similar character to it. Instead of doctrinaire pronouncements of ministers about various moral and ethical topics, the experience of faith is one of awareness of divine presence.

The theology and arts symposium this fall at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary drew upon the theological understanding of human experience embodied in the realness of a world that corresponds to divine intention in creation. These words are different than the scientific terminology of the physical sciences. Are they incommensurate? Or are they two expressions of consciousness arrived at from different starting points?

The conference program described the perspective that artist Edward Knippers approached his work.

“Disembodiment is not an option for the Christian.” This statement by visual artist Edward Knippers is a guiding principle in his work, which features the human body, often in connection with biblical scenes. Disembodiment is not an option for those who believe that human beings are created in God’s image with beautiful bodies, that everything from sin to salvation are embodied experiences, and that God’s redemption comes through the broken and risen body of Jesus. The paintings of Edward Knippers invite us to consider the goodness, brokenness, mystery, and glory of embodiment, urging us to grapple with the temptation to avoid, sexualize, downplay, or disparage bodies along with a fully embodied faith.

The Resurrection - 2007

Edward Knippers

The idea of embodied faith is a reflection of what theologians call the incarnation of God in Jesus of Nazareth. It means that God, the creator of heaven and earth, left the realm of uncreated eternity and entered into created time and space as a child. The Christmas story is the story of divine embodiment through the incarnation of God in human flesh. Not a divine mystical embodiment or symbolic (simulated) embodiment as a public religious figure, but real embodiment as a flesh and blood human being.

If God became a human being, what patterns of behavior would we expect to see? It is an important question because our perceptions about God are similar to perceptions about life and people, institutions and politics. We believe that our perceptions precede truth, or at least validate truth as we see it. In essence, Point-of-View Precedes Perception. To say it so blatantly, many of you might recoil in offense. Yet my observations of human behavior is that we operate as Paul Simon characterized in his famous song The Boxer, “we believe what we want to believe and disregard the rest.”

Does perception precede consciousness? I do not believe so. Rather, I believe that consciousness or awareness is more like a non-verbal language speaking to us through experience. If we open ourselves to experience, we may see things that were not possible if our predetermined perceptions formed our expectations for reality.

If the creator of all life appeared on earth (please accept the premise for the moment) what would that life appear to us looking like? My assumption is that he or she would look and act as we do. What else could we expect? Look at how we project our own sense of right and wrong on to leaders of organizations, nations, and communities. What should they be like? Is there some body of universal truth that should guide us in our judgement about these large scale questions? If God took on human flesh and entered our world, how would we know?

This is a question that often appears during the season of Christmas. The Spectacle of Jesus entering the world as a child, living an itinerant life as a wandering Rabbi, finally arrested, sentenced to death, and crucified as a political insurrectionist is not the story we would expect to find. Our orientation toward public leadership is that it is a function of ego and exploitation of the people. However if you read the Gospels, the stories show a very different pattern.

The Apostle Paul, who as Saul, was a great skeptic and persecutor of the followers of Jesus had an awakening of consciousness that transformed his life. In a letter to the church in Phillipi, he wrote,

If then there is any encouragement in Christ, any consolation from love, any sharing in the Spirit, any compassion and sympathy, make my joy complete: be of the same mind, having the same love, being in full accord and of one mind. Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves. Let each of you look not to your own interests, but to the interests of others. Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus,

who, though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited,

but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.

And being found in human form,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.Therefore God also highly exalted him

and gave him the name

that is above every name,

so that at the name of Jesus

every knee should bend,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

and every tongue should confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father.Phillipians 2:1-11

Is this what we’d expect? We’d be surprised, and maybe a bit curious.

Paul is describing the embodied character of the man, Jesus of Nazareth, born to Mary and Joseph, who lived a life in many ways avoiding identification as The Son of God, until his time had come. His purpose was to show who God was in the flesh without spectacle. The story of his death, resurrection, and reappearance before ascending to heaven defies logic. The stickiness of this story over time suggests that this is not just any old story or myth, but a defining one.

The Question Before Us

As a life-long Presbyterian and a retired minister, I learned that becoming aware of the presence of the embodied Christ does not primarily come from a rational examination of the story. It comes from a growing consciousness of our lives in the context of the world as it is.

The Cartesian dilemma of believing - ‘I think therefore I am’ or ‘Perception is Reality’ - forces us to objectify that which is non-objectifiable. To objectify reality places us in an isolated, detached relationship to all that exists. We are not immersed in reality, but separate and disconnected, standing on the outside looking in.

We can certainly learn from experience. We can quantify it, create models to explain it, and create institutions to scale its experience. But to treat experience as a thing to examine alone places us outside the environment of reality. We will see our lives as a collections of things to be manipulated and discarded. As a result, we can never become truly conscious of ourselves, others, or the world we live in.

A question at the heart of this problem afflicts every one of us. Regardless of whether you are religious or not, atheist or theist, have crafted your own individual spirituality, or have no consciousness of your life in the context reality, the question that remains with us is:

“Who am I as a whole person?”

Labels and titles cannot answer this question. Calendars and address lists cannot. Only the experience of life lived and pondered for its meaning and purpose can answer this question.

When the Edward Knippers’ conference was announced as being about embodied faith, I knew that I had to attend. When the Iain McGilchrist conference was announced as being about The Future of Humanity, I knew that I to attend. Both conferences presented a picture of what embodiment means. At the two conferences, I saw a common ground emerging where people from the Christian tradition and other spiritual traditions can talk with those who represent the deep tradition of research into neuroscience and consciousness.

The knowledge gap between religion and science is closing as the experience of “embodiment” comes to claim a greater significance for our lives. The simple idea that we were not born as thinking machines, but rather as beings who learn through embodied experience points us towards our future.

This knowledge gap is a context of learning through experience. This is the basic notion of what embodiment means. We know this already because most of us reflect upon our experience, trying to make sense of it, so that we can improve our lives.

What then should we do?

Open yourself up to new experiences.

Listen, observe, and reflect upon what you experience.

Enter into conversations where you can explore what you are discovering.

Learn to discern truth in the context of your experience.

Tell your story of awareness of experience.

We are at the beginning of a historical transition. It is uncertain what will emerge as we begin to talk more with one another about our experiences in life.