Leadership and the Culture of Simulation (1)

How Leaders become oblivious to their own simulation.

The Problem of Leadership

Modern conceptions of leadership in organizations are THE vehicle for the culture of Simulation in our time. There is no more exaggerated and misunderstood topic. When I began to study the world of leadership in the mid-1980s, little did I know that it was preparing me to see this culture of Simulation that I wrote about earlier.

The problem isn’t simply that our conception of leadership is the triumph of the marketing of heroic and superlative figures. It is also the entry point for how organizations end up living in a dream world of unreality. The following account of a project shows how simulation is a way to hide from reality.

Too Little Too Late

In 2000, I was asked to join a group of consultants as a process facilitator to address a problem that a hosiery mill was having. This mill had been in operation since the early 1940s. It was family-owned and operated. The founder, still alive, came to the office every day. His son was the current president, his nephew was the operations manager, and his son-in-law, the sales and marketing manager.

The company had been losing money since the early 1990s. What explains a company losing money that doesn’t address this fact.

Are they oblivious?

Are they overly confident that things will magically turn around?

Is it simply that fact that no one knew what to do so they kept doing what they had always done.

My assessment is that each reason operated simultaneously which brought this company to the point of closure.

The operations manager finally put his foot down and forced management, the family, to address the elephant in the room. He had the most direct experience of watching the system fail. He forced the family to stop paying the founder a full-time salary. Then, he forced them to address the manufacturing process.

Our Process

Our team was brought in to conduct a review and provide recommendations for change. On the team were a data specialist, a consultant specializing in change processes, another consultant trained in a continuous improvement process for manufacturers created by Eliyahu Goldratt called Theory of Constraints, and me who was the facilitator of the communication between the team and the company.

The mill’s manufacturing process for making socks consisted of 17 steps or stations. At the time of our project, it took six weeks to make and ship a pair of men’s socks. You heard that right. Six weeks! The system had not changed in sixty years. They hired and trained for each station. That person would spend eight hours each day creating product inventory for that particular station. In other words, each station had a backlog of inventory. If you work in manufacturing, you already see the problems in this system.

Applying the Theory of Constraints Model

It was clear that change needed to happen. In order to know what to do you have to ask the right questions. Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints is a change process that focuses on inventory control.

“The rate of turnover or usage of inventory is an excellent measure of the performance and rate of change of manufacturing companies.”*

Seeing this situation, I wondered how long it had been since their inventory turned over. Imagine not turning your inventory over for a decade instead of once a month. As a result, using the Goldratt system, we addressed the highest leveraged constraint of the company’s operation. Following Goldratt, we asked the following questions.*

What to change? (Where is the constraint?)

What to change to? (What should we do with the constraint?)

How to cause the change? (How do we implement change?)

The first change we made was the reconfiguring of the manufacturing process. Instead of a string of 17 disconnected steps, the consultants drafted a single integrated system with the same 17 steps.

The second change was to get rid of all the unused inventory taking up space reminding everyone about how the former system worked.

The third change was to cross-train everyone on the manufacturing floor to be able to function in every station.

And, the fourth change was to only make socks for actual orders.

It all seemed so simple. As outsiders, the simplicity of the new system made sense. Once these changes were made the process of making socks went from six weeks down to six days.

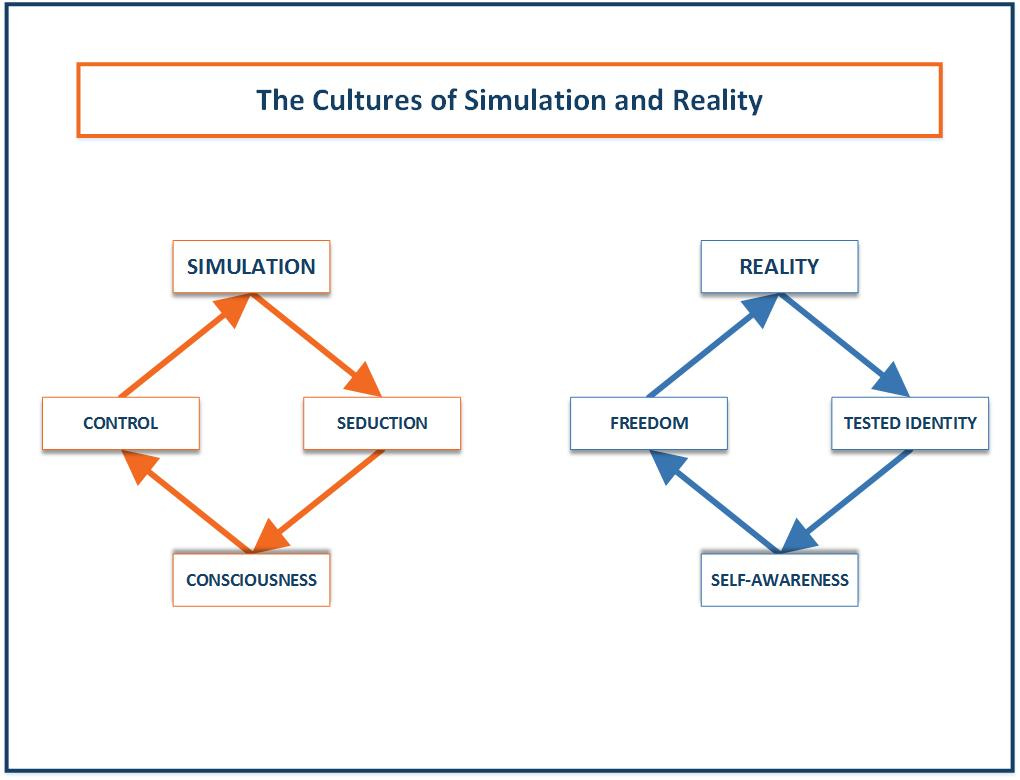

Simulation as Unconscious Cultural Practices

Yet when you have created a simulation-like environment that is immune to reality, this is what happens. You refuse to believe what everyone else can easily see. It is sort of like the old folk tale of the Emperor’s New Clothes. It is about the power of cognitive dissonance and confirmation bias to avoid facing reality. The current obsession of politicians and social media companies to root out disinformation is exactly this pattern of behavior. They are not interested in clarifying reality. No. They want to continue to live in their simulated reality, no matter how close it brings society to collapse. This is the mindset that had grown in this company.

During the 1990s, the place of values in business had a renaissance. Much of it was the product of Jim Collins and Jerry Porras’s book, Built To Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies.*** The one thing that stuck with me all these years is the importance of having a core ideology.

Core Ideology = Core Values + Purpose

Core Values = The organization’s essential and enduring tenets – a small set of general guiding principles; not to be confused with specific cultural or operating practices; not to be compromised for financial or short-term expediency.

Purpose = The organization’s fundamental reasons for existence beyond just making money – a perpetual guiding star on the horizon; not to be confused with specific goals or business strategies.

The problem that Collins and Porras identify is the one that the hosiery mill had, and many of my clients have had. Cultural practices are the result of the activities associated with “the persistent, residual culture of values.” This becomes the culture of the organization. It can be healthy or illusory. When values lose their value, cultural practices become hardened and entrenched as “the way we have always done things.” This is the mindset of the Simulation. It is a denial of reality.

Collins and Porras recommend that companies Preserve the Core and Stimulate Progress. I like to think that the values and purpose of an organization are the foundation for everything else. Let values lose their vitality, and the foundation fails. This is what was happening at the hosiery mill. Whatever values the founder had at the company’s inception had long ago been replaced with operating practices that were leading the company down the road to closure.

Prior to our intervention, I interviewed the management team. I had thirty minutes with each one of them. I wanted to understand how they perceived the situation and their role in the process. Twenty-five minutes into my time with the sales and marketing director we were still talking about him trying to sell a piece of farmland that he owned. The rest of the team apart from the nephew who ran the manufacturing process were equally detached from reality.

At that time, the thought crossed my mind, how can this kind of thinking be happening? Are they so programmed by habit and not thinking to be unable to change at all? It is one of those patterns of behavior that I will address in another essay in this series.

Each Constraint, A Link in a Chain

It is important to understand that every organization operates as a system. The larger the company the easier it is to lose touch with reality and begin to think that everything is fine. The effect of our change proposal was to shorten the manufacturing timeframe from six weeks to six days. Now, if we were there to transform the whole operation, we would have moved to the next constraint. But we didn’t.

Once the manufacturing process was fixed, the problems at the company left the building and went into the marketplace. The company was dependent upon an outdated sales and order approach that basically required constant sales conversion.

The goal of our project was to fix the manufacturing process. Our failure was to not address the larger issue of what is the goal of their company. We were already using the Goldratt Theory of Constraints system. We should have moved to the largest constraint that they had.

William Dettmer in his book, Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints: A Systems Approach To Continuous Improvement, describes Goldratt’s perspective of seeing systems as chains.

“Goldratt likens systems to chains or networks of chains. … (the) goal is to transmit force from one end to the other. If you accept the idea that all systems are constrained in some way, how many constraints does this chain have?” **

The next constraint was their perception of the business. They saw themselves solely as a sock manufacturer. Their goal was to make socks. Their core ideology was the next weak link in the chain. The problem is that their perception had fashioned a simulation mindset to ignore the changes that were happening in business and specifically with manufacturers.

What they did not realize was that the information age had radically altered their business purpose. They needed a change of perception about who they were as a business. When you live in a Simulation, you can only see yourself as the Simulation defines you. If they lived in the Real-world, they would have understood that their clients, principally a large West Coast department store chain, not only needed socks to sell but also they needed management of the sock inventory at each store. They should have seen that they needed to reinvent themselves in order to save the company.

Unfortunately, the changes that were made with this project were too little too late. Eighteen months after the completion of the changes to the manufacturing process, the company closed.

Impact is Reality

This project coming at an early stage in my consulting career helped me to see patterns of behavior that are the real problems that leaders don’t want to face. In a general sense, there are people who run their businesses but do not know how to lead their businesses. Thinking that leadership of the business is more a creating a perception of leadership than leading. The problem is not understanding leading.

The inability to see that you are trapped in a simulated reality provides the wrong feedback. It keeps confirming that you keep doing the things you’ve always done. You keep reading the right books, hiring the right consultants, believing in the right ideas, and supporting the right people, and yet, things are not improving. They are actually getting worse.

This is why I came to focus on creating impact. Impact is a change that makes a difference that matters. As a speaker, my goal is not to give a great speech. My goal is to move someone in the room to change their life. I want to see someone “take personal initiative to create an impact that makes a difference that matters.” As a writer, I’m not primarily interested in how many people open the email. I am interested if what I wrote changed someone’s perception. As a consultant, I wanted to solve problems, but I found leaders didn’t want to solve the highest leveraged problem. They wanted to do something that made everyone feel good. Therefore, sustain the illusion of the Simulation.

For the hosiery mill, how should they have identified what impact looks like? It is a tough question. It is a tough one because most companies are not externally focused. They are internally focused on the measures that are the easiest to produce.

What is the impact that you want from your life? From your work? For your family?

It is dependent upon what your values are and how those values define your purpose. See how focusing on the impact of values and the impact of your purpose, the impact of your relationships, and the impact of your workforce, you force out of the dull-headedness of the Simulation in order to discover a genuine brightness and energy for what you are going to do every day.

This is the beginning of a new series on Leadership and The Culture of Simulation. If you have not read the previous series, Reality and the Culture of Simulation here are links to the five essays, and to the original one that I wrote in 2013, The Spectacle of the Real.