Resources for Recovering Our Humanity through Writing and Conversation

Conversation Across Your Networks, Part 5. A series focused on conversation within The Networks of Relationships Series.

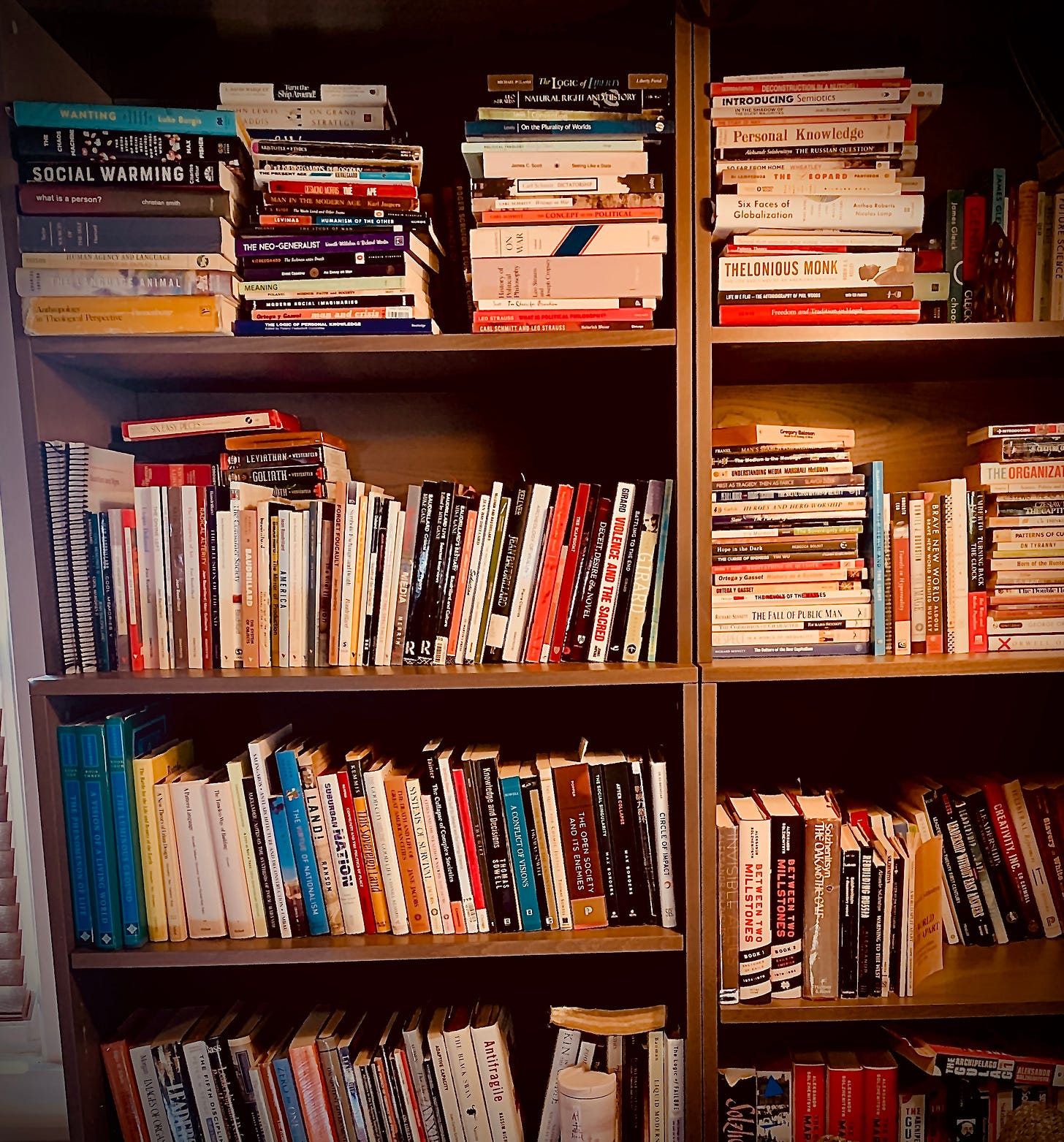

What am I Reading?

I am not a particularly original thinker. When I have come up with a unique idea (see Circle of Impact), it has come after years of study. For this reason, I figure I am more like you than we collectively are like those who are the elite intellectuals, like Einstein. I think it is therefore helpful to see how I arrive at what I write about. As you will see, I am inviting you to imitate what I am doing.

Imitate, not only by writing but also by reading through works that no matter what level of education you have had, with persistence, you can discover something there.

Think of this as the first collection of selections of people that I have been reading to have a clearer sense of the questions related to us as human persons. This is not exhaustive, or particularly systematic. It is just what I have been working through lately.

How should you read any of this? Assume that the text is more precisely written than you are used to. That’s okay. Take away what you can lay aside what isn’t helpful Also assume that there may be a hidden thread that ties them all together. The first person to identify that thread I’ll send a free copy of my Circle of Impact book. Let me know here with Subject: Thread.

Desmond Morris, The Naked Ape

There are one hundred and ninety-three living species of monkeys and apes. One hundred and ninety two of them are covered with hair. The exception is a naked ape self-named Homo sapiens. This unusual and highly successful species spends a great deal of time examining his higher motives and an equal amount of time studiously ignoring his fundamental ones.

Max Fisher, The Chaos Machine,

“When Facebook was getting going, I had these people who would come up to me and they would say, ‘I’m not on social media,’” Sean Parker, who had become Facebook’s first president at age twenty-four, recalled years later. “And I would say, ‘Okay, you know, you will be.’ And they would say, ‘No, no, no. I value my real-life interactions. I value the moment. I value presence. I value intimacy.’ And I would say, “We’ll get you eventually.’” …

Facebook’s strategy, as he described it, was not so different from Napster’s. But rather than exploiting weaknesses in the music industry, it would do so for the human mind. “The thought process that went into building these applications, “ Parker told the media conference, “was all about, ‘How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible?’” To do that, he said, “We need to sort of give you a little dopamine hit every once in a while, because someone liked or commented on a photo or a post or whatever. And that’s going to get you to contribute more content, and that’s going to get you more likes and comments.“ He termed this the “social-validation feedback loop, “ calling it “exactly the kind of thing that a hacker like myself would come up with, because you’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.” He and Zuckerberg “understood this” from the beginning, he said, and “we did it anyway.”

… Nir Eyal, a prominent Valley product consultant … “Our actions have been engineered … habitually alter our everyday behavior, just as their designers intended.”

One of Eyal’s favorite models is the slot machine. It is designed to answer your every action with a visual, auditory, and tactile feedback.

The reason is a neurological chemical called dopamine … Your brain releases small amount of it when you fulfill some basic need, whether biological (hunger, sex) or social (affection, validation). Dopamine creates a positive association with whatever behaviors prompted its release, training you to repeat them. But when that dopamine reward system gets hijacked, it can compel you to repeat self-destructive behaviors. To place one more bet, binge on alcohol – or spend hours on apps even when they make you unhappy.

Dopamine is a social media’s accomplice inside your brain. It’s why your smartphone looks and feels like a slot machine, pulsing with colorful notification badges, whose sounds, and gentle vibrations. Those stimuli are neurologically meaningless on their own. But your phone pairs them with activities, like texting a friend or looking at photos, that are naturally rewarding.

Social apps hijack a compulsion – a need to connect – that can be even more powerful than hunger or greed. Eyal describes a hypothetical woman, Barbra, who logs on to Facebook to see a photo uploaded by a family member. As she clicks through more photos or comments in response, her brain conflates feeling connected to people she loves with the bleeps and flashes of Facebook’s interface. “Over time,” Eyal writes, “Barbar begins to associate Facebook with her need for social connection.“ She learns to serve that need with a behavior – using Facebook – that in face will rarely fulfill it.

Soon after Facebook’s news-feed breakthrough, the major social media platforms converged on what Eyal called the casino’s most powerful secrets: intermittent variable reinforcement. The concept, while sounding esoteric, is devilishly simple. The psychologist B. F. Skinner found that if he assigned a human subject a repeatable task – solving a simple puzzle, say – and rewarded her every time she completed it, she would usually comply, but would stop right after he stopped rewarding her. But if he doled out the reward only sometimes, and randomized its size, then she would complete the task far more consistently, even doggedly. And she would keep completing the task long after the rewards had stopped altogether = as if chasing even the possibility of a reward compulsively.

Slot machines leverage this psychological weakness to incredible effect. The unpredictability of the payout makes it harder to stop. Social media does the same. Posting on Twitter might yield a big social payoff, in the form of likes, retweets, and replies. Or it might yield no reward at all. Never knowing the outcome makes it harder to stop pulling the lever. Intermittent variable reinforcement is a defining feature of not only gambling and addition but also, tellingly, abuse relationships. Abusers veer predictably between kindness and cruelty, punishing partners for behavior that they had previously reward with affection. This can lead to something called traumatic bonding. The victimized partner finds herself compulsively seeking a positive response, like a gambler feeding a slot machine, or a Facebook addict unable to log off from the platform – even if, for many, it only makes them lonelier.

Further, while posting to social media can feel like a genuine interaction between you and an audience, there is one crucial, invisible difference. Online, the platform acts as unseen intermediary. It decides which of your comments to distribute to whom and in what context. Your post might get shown to people who will love it and applaud, or to people who will hate it and heckle, or to neither. You’ll never know because its decisions are invisible. All you know is that you hear cheers, boos, or crickets.

Luke Burgis, Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life

Mimetic desire, because it is social, spreads from person to person and through a culture. It results in two different movements – two cycles – of desire. The first cycle leads to tension, conflict, and volatility, breaking down relationships and causing instability and confusion as competing desires interact in volatile ways. This is the default cycle that has been most prevalent in human history. It is accelerating today.

It is possible to transcend that default cycle, though. It’s possible to initiate a different cycle that channels energy into creative and productive pursuits that serve the common good. … They’re fundamental to human behavior. Because they are so close to us – because they operate within us – we tend to look past them. Yet these cycles are at work constantly.

Nobody likes to think of themselves as imitative. We value originality and innovation. We are attracted to renegades. But everybody has hidden models … two kinds of model affect us in different ways: those who are outside our immediate world and those who are inside of it. Mimesis has different consequences in each case. …

We’re more threatened by people who want the same things as us than by those who don’t. Ask yourself, honestly, whom are you more jealous of? Jeff Bezos, the richest man in the world? Or someone in your field, maybe even in your office, who is as competent as you are and works the same amount of hours you do but who has a better title and makes an extra $10,000 per year? It’s probably the second person.

That is how rivaly is a function of proximity. When people are separated from us by enough time, space, money, or status, there is no way to compete seriously with them for the same opportunities. We don’t view models in Celebristan as threatening because they probably don’t care enough about to adopt our desires as their own.

Thre is another world, though, where most of us live the majority of our lives. We’ll call in Freshmanistan. People are in close contact and unspoken rivalry is common. Tiny differences are amplified. Models who live in Freshmanistan occupy the same social space as their imitators. …

René Girard calls models in Celebristan external mediators of desire. …

Hierarchies in companies can create barriers to competition, making it practically impossible for some people to compete with others for the same roles and accolades. …

Freshmanistan is the world of models who mediate dsire from inside our world, which is why Girard calls them internal mediators of desire. There are no barriers preventing people from competing directly with one another for the same thing.

Between social media, globalization, and the toppling of old institutions, most of us are living nearly our entire lives in Freshmanistan. …

Celebristan (World of External Mediation)

· Models are distant in time, space, or social status

· Models are Different

· Models are easy to identify

· Models provide Open Imitation

· Models are acknowledged

· Relatively stable, fixed Models

· No possibility of conflict between models and imitators

· Positive mimesis is possible

Freshmanistan (World of Internal Mediation)

· Models are close in time, space, or social status

· Models are Same

· Models are hard to identify

· Secret imitation

· Models unrecognized

· Unstable, constantly changing models

· Conflict between models and imitators is normal

· Negative mimesis is the norm

Christian Smith, What is a Person?

It is impossible to understand properly the world or ourselves as human beings without understanding the idea and reality of emergence. Emergence refers to the process of constituting a new entity with its own particular characteristics through the interactive combination of other, different entities that are necessary to create the new entity. Emergence involves the following: First, two or more entities that exist at a “lower” level interact or combine. Second, that interaction or combination serves as the basis of some new, real entity that has existence at a “higher” level. Third, the existence of the new higher-level entity is fully dependent upon the two or more lower-level entities interacting or combining, as they could not exist without doing so. Fourth, the new, higher-level entity nevertheless possesses characteristic qualities (e.g., structures, qualities, capacities, textures, mechanisms) that cannot be reduced to those of the lower-level entities that gave rise to the new entity possessing them. When these four things happen, emergence has happened. The whole is more than the sum of its parts. …

As Michael Polanyi observed, “You cannot derive a vocabulary from phonetics; you cannot derive a grammar of language from its vocabulary; a correct use of grammar does not account for good style; and a good style does not provide the content of a piece of prose. … It is impossible to represent the organizing principles of a higher level by the laws governing its isolated particulars.(from The Tacit Dimension, 36). …

Reality is thus significantly constituted through relationality, not merely composition. …

Human Capacities

… to show that a series of real, distinct, interrelated causal capacities are emergent from the human body, particularly from the human brain, as it operates in its material and social environment. By causal capacities I mean that these powers endow humans with the ability to bring about changes in material or mental phenomena, to produce or influence objects and events in the world. Humans share many similarities of basic genetics and body structure with other primates, to whom we are most closely related biologically. But many of these causal capacities are distinctively human in extent, intensity, and quality, and so set humans uniquely apart from these and other animals. The causal capacities I describe do not themselves constitute human personhood. Personhood is emergent from them. But they do form some of the key elements from which, as they interact, human personhood is emergent. These causal capacities thus mediate between the real human body and real human personhood. …

The first is the capacity for consciousness, which human also share with many living creatures. Much that exists in reality is not conscious. My mailbox, for instance, is not conscious. But the operation of the physical matter that composes brains and bodies of humans and most other animals somehow gives rise to subjective awareness of existence. As conscious creatures, human are able to take in, be attentive of, and respond to external data. Consciousness at a basic level means that human can exist in a state of being that is sentient, wakeful, alert, aware, attentive. Humans also possess what we might think of as involuntary capacities. One is to live in a part of a state of unconscious being. Not all of the desires, feelings, beliefs, dispositions, and goals that govern people’s affect and actions are immediately assessable to their conscious inspection. Part of the normal human being’s personality and motivational structure exists “below the surface” of awareness and recognition – even if they are shaped by ongoing conscious processes. This we call the unconscious, the depths of which in its influence on complex behavior appear to be extensive among humans.

Among their basic mental abilities, humans possess the natural capacity to understand the real properties of quantity, quality, time, and space. This ability provides humans with the basic ordering and representational categories for understanding the crucial features of the real environment about which human perception provides information. As conscious animals, humans are also capable of mental representation, of forming cognitive depictions of reality.

Alasdair MacIntyre, Dependent Rational Animals

What then are the salient and relevant characteristics of human language, exemplified in the more than four and a half thousand natural languages of human cultures? First, every natural language has a vocabulary, a stock of words, and a stock of expressions, many of them consisting of a string of words … rather than a single word. The speakers of each particular language have a stock of shared phonemes that enable them to pronounce those expressions recognizably and sometimes have a stock of written signs that serve the purpose of written utterance. Secondly, a language has a set of rules for combining expressions, so as to form sentences. These rules constitute the syntax of the language. Simple sentences, decomposable into expressions, but not into further sentences, can be combined in various ways to form further sentences of indefinite length and complexity. Thirdly the types of expression that make up sentences include names, definite descriptions, predicates, quantifiers, demonstratives, pronouns, and such other indexicals as ‘here’ and ‘now’, and those logical connectives that make possible negation, disjunction, conjunction, and relations of logical implication, entailment and equivalence. The relationship between a name and its bearer, between a description and that to which it applies, between a demonstrative or a pronoun and that which is referred to by its use and between such indexicals as ‘here’ and ‘now’ and the times and places to which they refer have to be understood, if those types of expression are to be understood and to provide a language with semantic dimension.

Harry Frankfurt, Freedom of the Will and The Concept of the Person

It is my view that one essential difference between persons and other creatures is to be found in the structure of a person’s will. Human beings are not alone in having desires and motives, or in making choices. They share these things with the members of certain other species, some of whom appear to engage in deliberation and to make decisions based upon prior thought. It seems to be peculiarly characteristic of humans, however, that they are able to form what I shall call “second-order desires” or “desires of the second order.

Besides wanting and choosing and being moved to do this or that, men may also want to have ( or not to have) certain desires and motives. They are capable of wanting to be different, in their preferences and purposes, from what they are. May animals appear to have the capacity for what I shall call “first order desires” or “desires of the first order, “ which are simply desires to do or not to do one thing or another. No animal other than man, however, appears to have the capacity for reflective self-evaluation that is manifested in the formation of second-order desires.

Just what kind of freedom is the freedom of the will? This question calls for an identification of the special area of human experience to which the concept of freedom of the will, as distinct from the concepts of other sorts of freedom, is particularly germane. … According to one familiar philosophic tradition, being free is fundamentally a matter of doing what he wants to do. Now the notion of an agent who does what he wants to do is by no means an altogether clear one: both the doing and the wanting, and the appropriate relation between them as well, require elucidation. But although its focus needs to be sharpened and its formulation refined, I believe that this notion does capture at least part of what is implicit in the idea of an agent who acts freely. It misses entirely, however, the peculiar content of the quite different idea of an agent whose will is free.

We do not suppose that animals enjoy freedom of the will, although we recognize that an animal may be free to run in whatever direction it wants. Thus, having the freedom to do what one wants to do is not a sufficient condition of having a free will. It is not a necessary condition either. For to deprive someone of his freedom of action is not necessarily to undermine the freedom of his will. When an agent is aware that there are certain things he is not free to do, this doubtless affects his desires and limits the range of choices he can make. But suppose that someone, without being aware of it, has in fact lost or been deprived of his freedom of action. Even though he is no longer free to do what he wants to do, his will may remain as free as it was before. Despite the fact that he is not free to translate his desires into actions or to act according to the determinations of his will, he may still form those desires and make those determinations as free as if his freedom of action had not been impaired.

When we ask whether a person’s will is free we are not asking whether he is in a position to translate his first-order desires into actions. That is the question of whether he is free to do as he pleases. The question of the freedom of his will does not concern the relation between what he does and what he wants to do. Rather, it concerns his desires themselves. But what question about them is it?

It seems to me both natural and useful to construe the question of whether a person’s will is free in close analogy to the question of whether an agent enjoys freedom of action. Now freedom of action is (roughly, at least) the freedom to do what one wants to do. Analogously, then, the statement that a person enjoys freedom of the will means (also, roughly) that he is free to want what he wants to want. More precisely, it means that he is free to will what he wants to will, or have the will he wants. Just as the question about the freedom of an agent’s action has to do with whether it is the action he wants to perform, so the question about the freedom his will has to do with whether it is the will he wants to have.

It is in securing the conformity of his will to his second-order volitions, then, that a person exercises freedom of the will. And it is in the discrepancy between his will and his second-order volitions, or in his awareness that their coincidence is not his own doing but only a happy chance, that a person who does not have this freedom feels its lack. The unwilling addict’s will is not free. …

My theory concerning the freedom of the will accounts easily for our disinclination to allow that this freedom is enjoyed by the members of any species inferior to our own. It also satisfies another condition that must be met by any such theory, by making it apparent why the freedom of the will should be regarded as desirable. The enjoyment of a free will means the satisfaction of certain desires – desires of the second or of higher orders – whereas its absence means their frustration. The satisfactions at stake are those which accrue to a person of whom it may be said that his will is his own. The corresponding frustrations are those suffered by a person of whom it may be said that he is estranged from himself, or that he finds himself a helpless or a passive bystander to the forces that move him.

A person who is free to do what he wants to do may yet not be in a position to have the will he wants. Suppose, however, that he enjoys both freedom of action and freedom of the will. Then he is not only free to do what he wants to do; he is also free to want what he wants to want. It seems to me that he has, in that case, all the freedom it is possible to desire or to conceive. There are other good things in life, and he may not possess some of them. But there is nothing in the way of freedom that he lacks.

Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self

“… an ideal of self-responsibility, with the new definitions of freedom and reason which accompany it, and the connected sense of dignity. To come to live by this definition – as we cannot fail to do, since it penetrates and rationalizes so many of the ways and practices of modern life – is to be transformed: to the point where we see this way of being as normal, as anchored in perennial human nature in the way our physical organs are. So we come to think that we “have” selves as we have heads. But the very idea that we have or are “a self”, that human agency is essentially defined as “the self”, is a linguistic reflection of our modern understanding and radical reflexivity it involves. Being deeply embedded in this understanding, we cannot but reach for this language; but it was not always so.” … I look as my guiding thread the successive understandings of the moral ideal of self-mastery. This was the basis of the contrast between Plato and Descartes. But the line of development through Augustine has also generated models of self-exploration which have crucially shaped modern culture.

Augustine’s inward turn was tremendously influential in the West; at first in inaugurating a family of forms of Christian spirituality, which continued throughout the Middle Ages, and flourished again in the Renaissance. But then later this turn takes on secularized forms. We go inward, but not necessarily to find God; we go to discover or impart some order, or some meaning or some justification, to our lives. In retrospect, we can see Augustine’s Confessions as the first great work in the genre which includes Rousseau’s work of the same title, Goethe’s Dichtung und Wahrheit, Wordsworth’s Prelude – except the Bishop of Hippo antedates his followers by more than a millennium.

To the extent that this form of self-exploration becomes central to our culture, another stance of radical reflexivity becomes of crucial importance to us alongside that of disengagement. It is different and in some ways antithetical to disengagement. Rather than objectifying our own nature and hence classing it as irrelevant to our identity, it consists in exploring what we are in order to establish this identity, because the assumption behind modern self-exploration is that we don’t already know who we are.

There is a turning point here whose representative figure is perhaps Montaigne. There is some evidence that when he embarked on his reflections, he shared the traditional view that these should serve to recover contact with the permanent, stable, unchanging core of being in each of us. This is the virtually unanimous direction of ancient thought: beneath the changing and shifting desires in the unwise soul, and over against the fluctuating fortunes of the external world, our true nature, reason, provides a foundation, unwavering and constant.

For someone who holds this, the modern problem of identity remains unintelligible. Our only search can be to discover within us the one universal human nature. But things didn’t work out this way for Montaigne. There is some evidence that when he sat down to write and turned to himself, he experienced a terrifying inner instability. … And from this emerged a quite different stand towards impermanence and uncertainty of human life, an acceptance of limits …

There is a question about ourselves – which we roughly gesture at with the term “identity” – which cannot be sufficiently answered with any general doctrine of human nature. The search for identity can be seen as the search for what I essentially am. But this can no longer be sufficiently defined in terms of some universal description of human agency as such, as soul, reason, or will. There still remains a question about me, and that is why I think of myself as a self. This word not circumscribes an area of questioning. It designates the kind of being of which at this question of identity can be asked.

Charles Taylor, Human Agency and Language: Philosophical Papers 1

The key notion is the distinction between first- and second-order desires which Frankfurt makes … I can be said to have a second-order desire when I have a desire whose object is my having a certain (first-order) desire. The intuition underlying Frankfurt’s … notion is that it is essential to the characterization of a human agent or person that is to the demarcation of human agents from other kinds of agent. … Put in other terms, we think of (at least higher) animals as having desires, even as having to choose between desires in some cases, or at least as inhibiting some desires for the sake of others. But what is distinctively human is the power to evaluate our desires, to regard some as desirable and others as undesirable. This is why “no animal other than man … appears to have the capacity for reflective self-evaluation that is manifested in the formation of second-order desires. …

But what is missing … is a qualitative evaluation of my desires; the kind of thing we have, for instance, when we refrain from acting on a given motive – say, spite, or envy – because I consider it base or unworthy. In this kind of case our desires are classified in such categories as higher and lower, virtuous and vicious, more and less fulfilling, more and less refined, profound, and superficial, noble and base. They are judged as belonging to qualitatively different modes of life: fragmented or integrated, alienated or free, saintly, or merely human, courageous or pusillanimous and so on.

Intuitively, the difference might be put in this way. In the first case, which we may call weak evaluation, we are concerned with outcomes; in the second, strong evaluation, with the quality of our motivation. But just put this way, it is a little too quick. For what is important is that strong evaluation is concerned with the qualitative worth of different desires.

Charles Taylor, Modern Social Imaginaries

As long as society is seen as by its very nature cohering only as subject to the kind or as ruled by its ancient law, because in each case this is what links our society to its grounding in higher time, it is hard to imagining it in any other terms or from any other angle. To see it just as a system, as set of connected processes, operating impartial independence from its political or legal or ecclesial ordering, requires this shift into pure secular time. It requires a perspective on society as a whole independent from the normative ordering that defines its coherence as a political entity. …

So the new horizontal world in secular time allows for two opposite ways of imagining society. On one side, we become capable of imagining new free, horizonal modes of collective agency, and hence of entering into and creating such agencies because they are now in our repertoire. On the other, we become capable of objectifying society as a system norm-independent processes, in some ways analogous to those in nature. On the one hand, society is a field of common agency, on the other a terrain to be mapped, synoptically represented, analyzed, perhaps preparatory to being acting on from the outside by enlightened administrators. …

… these two standpoints cannot be dissociated. They are coeval; they belong together to the same range of imaginings that derive from the modern moral order.

Central to this is the idea that the political is limited by the extrapolitical, by different domains of life that have their own integrity and purpose. These include but aren’t exhausted by the economic.

Ernst Cassier, An Essay on Man

“No longer in a merely physical universe, man lives in a symbolic universe. Language, myth, art, and religion are parts of this universe. They are the varied threads which weave the symbolic net, the tangled web of human experience. All human progress in thought and experience refines upon and strengthens this net. No longer can man confront reality immediately; he cannot see it, as it were face to face. Physical reality seems to recede in proportion as man’s symbolic activity advances. Instead of dealing with the things themselves man is in a sense constantly conversing with himself. He has so enveloped himself in linguistic forms, in artistic images, in mythical symbols or religious rites that he cannot see or know anything except by the interposition of this artificial medium. Even here man does not live in a world of hard facts, or according to his immediate needs and desires. He lives rather in the midst of imaginary emotions, in hopes and fears, in illusions and disillusions, in his fantasies and dreams. “What disturbs and alarms man,” said Epictetus, “are not the things, but his opinions and fancies about the things.”

Søren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death: A Christian Psychological Exposition for Upbuilding and Awakening

“A human being is spirit. But what is spirit? Spirit is the self. But what is the self? The self is a relation that relates itself to itself or is the relation's relating itself to itself in the relation; the self is not the relation but is the relation's relating itself to itself. A human being is a synthesis of the infinite and the finite, of the temporal and the eternal, of freedom and necessity, in short, a synthesis. A synthesis is a relation between two. Considered in this way a human being is still not a self.... In the relation between two, the relation is the third as a negative unity, and the two relate to the relation and in the relation to the relation; thus under the qualification of the psychical the relation between the psychical and the physical is a relation. If, however, the relation relates itself to itself, this relation is the positive third, and this is the self.”

Alexandr Solzhenitsyn

“Live Not By Lies”, Publically Released February, 12, 1974

We are approaching the brink; a universal spiritual demise is upon us; a physical one is about to flare up and engulf us and our children, while we continue to smile sheepishly and babble:

“But what can we do to stop it? We haven’t the strength.”

We have so hopelessly ceded our humanity that for the modest handouts of today we are ready to surrender up all principles, our soul, all the labors of our ancesters, all the prospects of our descendents – anything to avoid distrupting our meager existence. We have lost our strength, our pride, our passion. We do not even fear a common nuclear death, do not fear a third world war (perhaps we’ll hide away in some crevice), but fear only to take a civic stance. We hope only not to stray from the herd, not to set ou on our own, and risk suddently having to make do without the white bread, the hot water heater, and a Moscow residency permit.

We have internalized well the lessons drummed into us by the state; we are forever content and comfortable with its premise: we cannot escape the environment, the social conditions; they shape us, “being determines consciousness.” What have we do with this? We can do nothing.

But we can do – everything! – even if we comfort and lie to ourselves that this is not so. It is not “they” who are guilty of everything, but we ourselves, only we!”

The Gulag Archipelago

“And how we burned in the camps later, thinking: What would things have been like if every Security operative, when he went out at night to make an arrest, had been uncertain whether he would return alive and had to say good-bye to his family? Or if, during periods of mass arrests, as for example in Leningrad, when they arrested a quarter of the entire city, people had not simply sat there in their lairs, paling with terror at every bang of the downstairs door and at every step on the staircase, but had understood they had nothing left to lose and had boldly set up in the downstairs hall an ambush of half a dozen people with axes, hammers, pokers, or whatever else was at hand?... The Organs would very quickly have suffered a shortage of officers and transport and, notwithstanding all of Stalin's thirst, the cursed machine would have ground to a halt! If...if...We didn't love freedom enough. And even more – we had no awareness of the real situation.... We purely and simply deserved everything that happened afterward.”

“You only have power over people as long as you don’t take everything away from them. But when you’ve robbed a man of everything, he’s no longer in your power–he’s free again.”

“Own only what you can always carry with you: know languages, know countries, know people. Let your memory be your travel bag.”

“… What about the main thing in life, all its riddles? If you want, I'll spell it out for you right now. Do not pursue what is illusionary -property and position: all that is gained at the expense of your nerves decade after decade, and is confiscated in one fell night. Live with a steady superiority over life -don't be afraid of misfortune, and do not yearn for happiness; it is, after all, all the same: the bitter doesn't last forever, and the sweet never fills the cup to overflowing. It is enough if you don't freeze in the cold and if thirst and hunger don't claw at your insides. If your back isn't broken, if your feet can walk, if both arms can bend, if both eyes can see, if both ears hear, then whom should you envy? And why? Our envy of others devours us most of all. Rub your eyes and purify your heart -and prize above all else in the world those who love you and who wish you well. Do not hurt them or scold them, and never part from any of them in anger; after all, you simply do not know: it may be your last act before your arrest, and that will be how you are imprinted on their memory.”

“Unlimited power in the hands of limited people always leads to cruelty.”

“Look around you--there are people around you. Maybe you will remember one of them all your life and later eat your heart out because you didn't make use of the opportunity to ask him questions. And the less you talk, the more you'll hear. Thin strands of human lives stretch from island to island of the Archipelago. They intertwine, touch one another for one night only in just such a clickety-clacking half-dark car as this and then separate once and for all. Put your ear to their quiet humming and the steady clickety-clack beneath the car. After all, it is the spinning wheel of life that is clicking and clacking away there.”

“A World Split Apart”, Harvard Commencement Address, 1978.

"A decline in courage may be the most striking feature that an outside observer notices in the West today. The Western world has lost its civic courage, both as a whole and separately, in each country, in each government, in each political party, and of course, in the United Nations. Such a decline in courage is particularly noticeable among the ruling and intellectual elites, causing an impression of a loss of courage by the entire society. There remain many courageous individuals, but they have no determining influence on public life."

"I have spent all my life under a Communist regime and I will tell you that a society without any objective legal scale is a terrible one indeed. But a society with no other scale but the legal one is also less than worthy of man. A society based on the letter of the law and never reaching anything higher fails to take advantage of the full range of human possibilities."

"And yet in early democracies, as in American democracy at the time of its birth, all individual human rights were granted on the ground that man is God’s creature. That is, freedom was given to the individual conditionally, in the assumption of his constant religious responsibility. Such was the heritage of the preceding one thousand years. Two hundred or even fifty years ago, it would have seemed quite impossible, in America, that an individual be granted boundless freedom with no purpose, simply for the satisfaction of his whims. Subsequently, however all such limitations were eroded everywhere in the West; a total emancipation occurred from the moral heritage of Christian centuries with their great reserves of mercy and sacrifice. State systems were becoming ever more materialistic. The West has finally achieved the rights of man, and even to excess, but man’s sense of responsibility to God and society has grown dimmer and dimmer."

“Men have forgotten God“ Templeton Lecture, 1983.

"More than half a century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of older people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: “Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened."

Since then I have spent well-nigh fifty years working on the history of our Revolution; in the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous Revolution that swallowed up some sixty million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: “Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.”