Intuition

If you spend as much time on the road as I do, (I have driven an average 20-25k miles a year for over thirty years.) you will have an experience where you realize that you have been driving for miles without being conscious of driving. You don’t know how many miles you’ve gone or how much time has passed. Maybe there was your favorite song playing that you are singing. You were talking on the phone. Or you are lost in thought listening to a podcast. Whatever it is, your conscious mind is occupied with one thing and your unconscious mind is focused on driving.

This thought came to me as I listened to Iain McGilchrist talk about intuition. In the podcast, he speaks about the annual Isle of Man TT motorcycle race. See in this short video of the race what the racers experience driving at 200 mph on the roads of the island.

Now, listen to his podcast on intuition and how it applies to the racers. That racing discussion begins at the 35-minute mark.

The intuition that McGilchrist describes is a part of the Synthetic perspective that I am describing here.

There are things that we can know and know why we know them. There are other things that we know that we don’t know how we know them. And then there are the things we know because of their connection to other things. This is how synthetic knowledge is a form of whole knowledge. Our minds synthesize an awareness or understanding that is whole and constantly expanding.

Try this experiment. Walk into a local coffee shop. Get your cup and sit down as you enjoy your coffee look at the people. Most will look non-descript. Their dress is unremarkable. Their facial expressions as well. Some will look anxious. A few will sparkle with happiness. You don’t have to go ask them. You are not judging these people. Instead, you are sizing them up to see who to begin a conversation. This is intuition. It is also a form of tacit knowledge.

Tacit Knowledge

Michael Polanyi, a chemist, and philosopher describes Tacit knowledge this way.

“Tacit knowledge is a central part of knowledge … we can both (1) know what to look for, and (2) have some idea about what else we may want to know. … tacit knowledge achieves comprehension by indwelling, and that all knowledge consists of or is rooted in such acts of comprehension”

In this sense, tacit knowledge embodies a focus on what we want to know. The engine of tacit knowledge we could describe as curiosity or the desire to know, to discover, to explore, to answer questions that seem to have no fixed or certain answer. This knowledge is experienced as intuition. The faces on the people tell us something about their current state of mind.

We all have questions.

Tacit knowledge emerges from the intersection of the analytical and experiential and becomes intuitive knowledge.

We see what we did not consciously realize we were seeking. The surprise, the A-Ha moment, the insight that changes our perception of the world and of ourselves is a product of this synthesizing process that is always active within us.

Several months back I wrote a piece called, We Learn Iteratively and Emergently. This was my first attempt at describing the idea of Synthetic Knowledge. There I wrote,

We learn by repetition, not only by the act of practicing over and over again but by relearning in new contexts.

Iterative learning takes place in the context of networks of relationships.

We make mistakes. We fall down. We get up. We try again.

Real, deep learning emerges step-by-step, iteratively.

We learn from each other.

We change.

We ask for help. We offer help.

We are transformed, over and over again, day-by-day, week-by-week, year-by-year, all through our lives,

This is how iterative learning emerges in our lives.

Iterative, emergent learning is transformational.

Transformational is life lived at the edge of fulfillment and growth.

In our networks of relationships, this is how we can learn to change.

In my post, the Synthetic Network, I explain what I mean by Synthetic.

“… synthetic knowledge … is open and is a synthetization of a wide range of categories of knowledge. It is open and available online. It comes from many different sources so it requires all the various strands of knowledge to be woven together into a coherent, synthetic form. …

You cannot know what you do not know at the beginning of this process. You must open yourself up to people, perspectives, and intellectual resources that will be made relevant through the process of synthesis.

Do not accept anything as the default understanding of your situation. There is no such thing. At some point, you will begin to put pieces together, like a large puzzle. A picture of understanding will emerge. … Borrow, clip, glue, staple, cut-and-paste, and over time, you’ll have a bandwidth of knowledge that will be synthesized for application throughout every part of your life.

… I want you to see that synthesizing is how we make sense of what we learn. We are always asking, “Does this makes sense? How will this work?”

Think of every perspective, model, or design as simply tools for synthesis.

Is this model appropriate for this situation?

Does her perspective fit with what we are seeing? These are the kind of questions we should ask.

Habits

Another way of describing how we synthesize information to create knowledge is by creating habits. Check out these two writers on habits.

James Clear, Atomic Habits: Tiny Changes, Remarkable Results

Charles Duhigg, The Power of Habits: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business

All of us who practice skills of expertise and awareness owe a great debt of gratitude to the Greek philosopher Aristotle for giving us a deep philosophical rationale for learning through habit formation. Here I want to paraphrase him by replacing his term, Virtue, with the word, Learning.

“There is two kinds of learning, intellectual and practical. Intellectual learning owes its purpose and growth chiefly to instruction, and for this reason needs time and experience. Practical learning is the result of habit. This means that neither intellectual or practical knowledge comes to by being naturally born in us. … We learn everything by first practicing them. Anything we have to learn we learn by actual doing it: people become builders by building and become musicians by playing their instrument. In the same way, we become trustworthy by doing things in a trustworthy manner; we become patient by learning to be patient when we are tempted to impatient. We learn to be brave by doing brave deeds.” (Paraphase of Aristotle’s Nichomachen Ethics, Book II.)

This is how we learn to create Synthetic knowledge.

The Asymmetric Brain Synthesizes Sensory Experience

I want to return to Iain McGilchrist because his work describes the science behind what I am calling Synthetic learning. In his fascinating book, The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World , McGilchrist writes about asymmetries in nature.

“In the physics that makes the world possible, chaos and rigidity must be very finely balanced. We need forces for stasis and conservation, and forces for flow and change: but they must work together. We can see this being played out in the task of balancing inherently contradictory or paradoxical elements as being both united and distinct in spatial terms as well as both stable and changeable in temporal terms. However, as elsewhere, there is an asymmetry between the force for division and the forces for union: ultimately they have to be united, not divided.”

McGilchrist’s central point in his book concerns the asymmetrical nature of the two hemispheres of the human brain.

“In terms of the hemispheres it is once more not a symmetrical, but an asymmetrical arrangement: not just between two dispositions (that of the left hemisphere and that of the right) towards the world, but between a disposition (that of the left) that sees the two dispositions as an antagonism that must ultimately lead to the triumph of the one and the annihilation of the other, and a disposition (that of the right) that sees they need to be preserved together, neither being allowed to extinguish the other – even though they are not of equal value.”

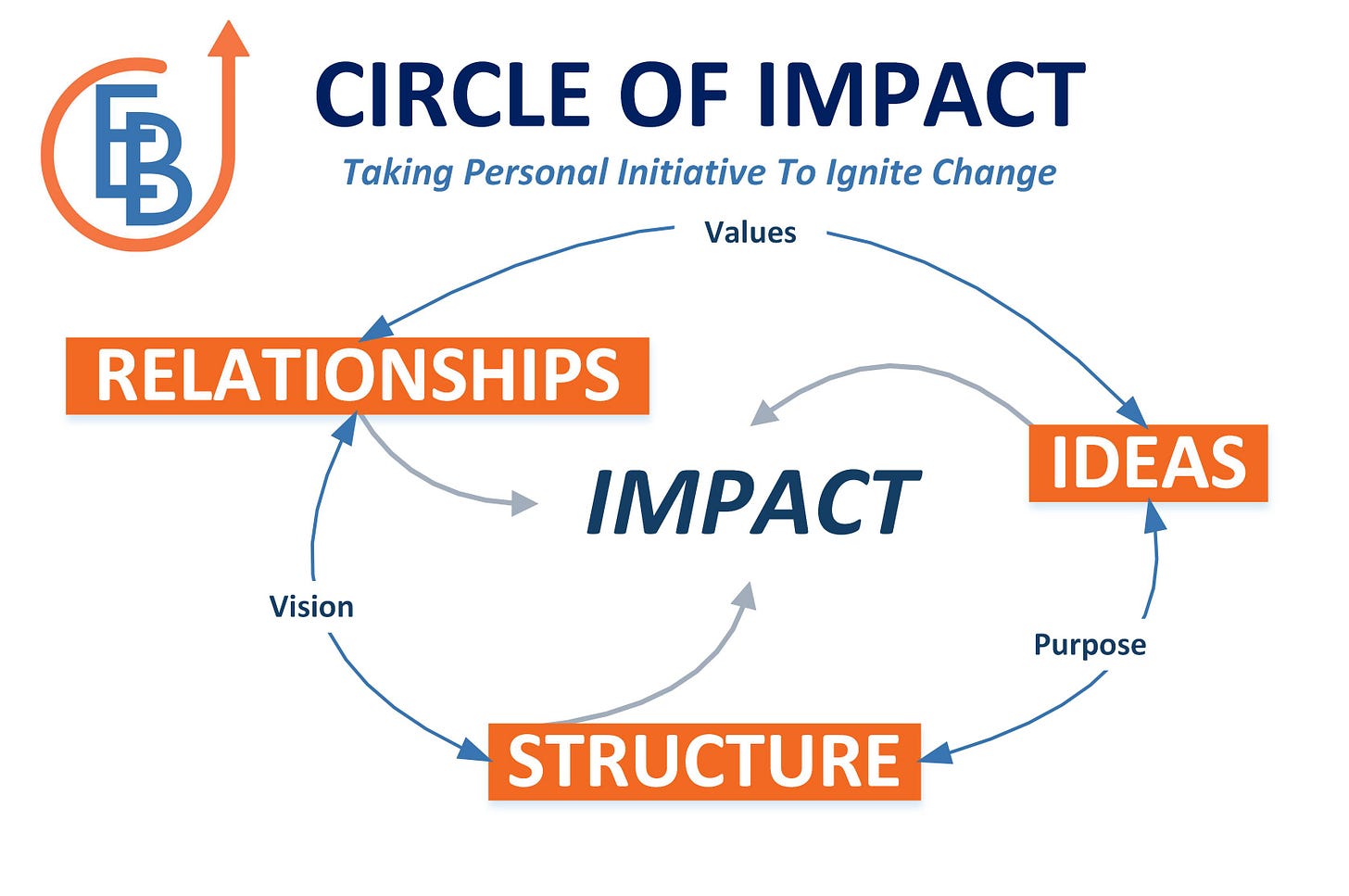

I learned to think in these terms in the mid-1990s. Through my consulting work, I saw patterns of behavior that were similar across a wide spectrum of organizational types. These patterns were not susceptible to identification by traditional analytical methods. In fact, because the patterns were the same, some may conclude that this is the way organizations are to function. However, the organizations were different in purpose and program. From this perspective of breadth, a synthetic understanding of the state of organizations emerged. I concluded that the structure of organizations is broken. They have fragmented along the boundaries that separate the three dimensions of my Circle of Impact model of leadership.

As I processed what I observed, I realized that there was a governing set of assumptions about organizations. In short, they were all alike. They were alike by following the same rules and strategies, creating the same structures, and as a result, falling prey to the same problems. The mindset represented a mechanical perception and application. There were rules and they were meant to be followed even if someone's intuition suggested something else.

I came to see that when we look at an organization from a mechanical point of view, we automatically negate the intuition and tacit knowledge aspects of our brain. They are creative functions, based on McGilchrist’s writings, found in the right hemisphere of the brain. The left hemisphere’s narrow analytical approach negates the embodied character of synthetic knowledge.

To function with only the left hemisphere, we could never learn to drive a car, ride a bike, ski down a mountain, or use standard typing methods on our computers. Each of these skill sets is learned by mastering skill sets through practice. We don’t learn how to fly fish by only reading a book. We go out in the yard and practice casting a fly. It isn’t easy. It takes practice. Once we have learned, we can then incorporate other aspects of fishing, like learning to spot the fish and know what the best fly to use is. This is how synthetic learning works.

The hard stuff that is really meaningful cannot be learned by the book. It is learning that is acquired through practice.

The Context of Synthetic Learning

Synthetic learning connects a wide range of information from diverse fields of knowledge in such a way that it makes sense in the moment of awareness. This is a very right-brain creative activity. If you only look at knowledge from a left-brain analytical perspective you end up with warring camps each declaring their perspective is the truth and their opponent’s perspective is misinformation. The world is too complex for this analytical approach to work. Unfortunately, the politicization of science and industry has eroded the institutional ground for synthetic learning to thrive. Anyone who has a more synthetic approach, like my Circle of Impact model of leadership, is met not with resistance but a lack of curiosity. I have been told it is too complicated or not linear enough. Of course, it isn’t, because it is whole knowledge embodied in every individual. Here’s an example of the difference between synthetic and analytical knowledge.

In the mid-1970s, I came to the conclusion that the organizing principle of nature is relationships. I know scientists want to see Darwin’s theory as that organizing principle. But evolution doesn’t happen unless there is a connectional relationship between all facets of life. This is what McGilchrist is showing us. Life has meaning because of its relationship to something else. We find meaning because of a relationship to people, certain places, and ideas that inspire values and purpose.

The context of all knowledge is the systemic relationship that happens all through nature.

This is true not just in human relationships, but institutional relationships, community relationships, planetary relationships, and transcendent spiritual relationships. We understand life, and our lives, by understanding our relationship to the world.

We learn to discern the trustworthiness of a person through the context of a person lying to us. When we see the detrimental side of lost trust, we can then see just how important trust is. We see trust played out in our first jobs, then when we marry, in our relationships to our children, and then later to their spouses and grandchildren. If we apply a traumatic loss of trust when we are young, we may never overcome its negative effect upon us. However, if we take that hardship, and work to learn how to recover from that loss of trust, we lose our cynicism about people as we have the chance to build a relationship with someone in the future.

This is why Aristotle’s approach to learning is an iterative, emergent, synthesizing process that affects the whole of our lives.

We don’t learn something once and for all time.

We learn by repeating the lessons over and over again. We learn by creating habits that are sustained in good times and hard. This is iterative learning.

This pattern of learning behavior tests us to see who we are. We gain self-awareness and freedom as a result. This is how our agency as human beings develops.

We learn not just about the world as a whole, but of ourselves and our place within that world. Out of this knowledge, we learn how to make a difference in the world. We decide what that difference is, and we pursue its impact as our purpose in life.

As our intuition and tacit knowledge grow, synthetic knowledge emerges as a whole picture of ourselves and the world. Through its acquisition, we become whole persons.

Important stuff here. Thanks for highlighting Iain McGilchrist's work. The more people who grok this the better.

This concept of intuitive mind reminds me of a Taoist quote: “Superior virtue is not aware of itself as virtue, hence it is virtue”.

Are people aware of this kind of intuitive knowledge (or learning) you are referring to? Is awareness a relevant property?