Introduction to the Annotated Spectacle of the Real

This post first published in May 2013 may be the most important piece of writing that I have ever done. There are more popular and appreciated writings, but none were as important as The Spectacle of the Real for identifying the cultural context of the first decades of the 2000s. I know many people turned away from a piece that had some difficult terminology to understand. However, as almost a decade has passed by since it first appeared, the marks of simulation and spectacle are more evident than ever before.

In the next set of posts within the Background Series: The Spectacle of the Real, I going to annotate the post to create a more complete way to understand these concepts. As I venture into this project, I am planning to divide up the annotation into several posts.

All the posts in this series are prepared for paid subscribers. At $7 per month, you’ll gain perspective and knowledge that is worth far greater. Thank you.

The Reality of Honor and Service

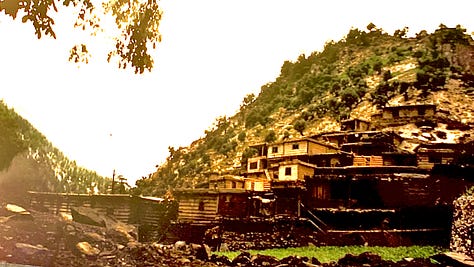

Afghan Mujahideen camp

Afghan / Soviet War

Chitral, NWFP, Pakistan

July 1981

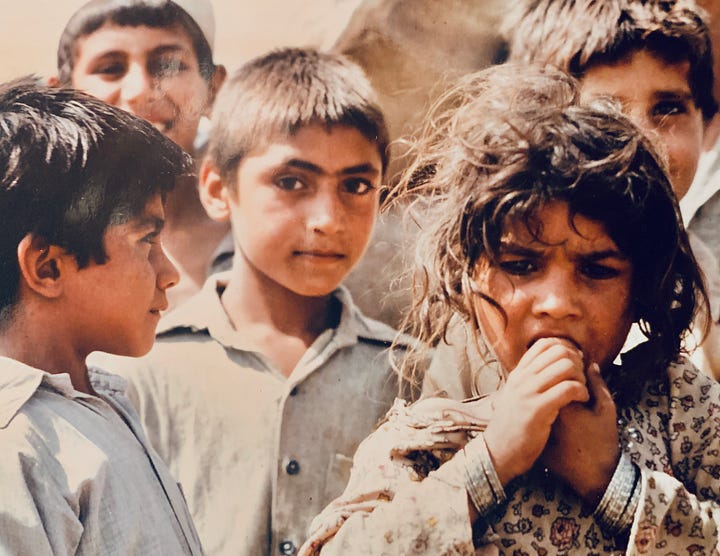

We live in a time of images. They form our understanding of history and engage us in the present. These faces of Afghan freedom fighters from four decades ago sustain a memory of an encounter that I had with them as a young refugee worker. This image helps me understand the continuity of history in the region.

This was a time soon after the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. Refugees were pouring over the mountain passes like this one near Chitral in the NorthWest Frontier Province seeking safety and security.

The Khyber Pass is the old Silk Road from East to West across the Euro-Asian continent. The border village of Torkham marks the border for transportation between Afghanistan and Pakistan. The day we were there, trucks and people were crossing with little difficulty. This includes a shepherd boy who took his small herd of goats across the Pakistan/Afghanistan border over the dry riverbed that marks that border.

But without that direct engagement, these images may seem more surreal than real. For there is no life context in which to interpret what was taking place when this picture was taken.

Just a few days after the above photographs were taken, this man, an Afghan refugee, honored me with an expression of thanks after our team of refugee workers brought food, clothing, and shelter to his refugee village on the desert plain outside of Peshawar, Pakistan.

This refugee encampment was in very poor condition. We spent some time with the elders of the group determining the size of their camp. We then drove back to Peshawar to load food, clothing, and shelter. In these pictures, you can see the condition of the people, especially the children, and the resources we brought back to them.

My experience in Pakistan in 1981 reminded me of the images that I saw of the Vietnam War on the evening news 15 years before. It was a complex war treated simplistically from an anti-American perspective. It pointed to the power of the visual image to create an alternative reality of the war. This is the power of simulation to affect perception.

In the next section of The Annotated Spectacle of the Real, I look at the coverage of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings and how they were representative of this growing simulation culture.