The Return of “The Strength of Weak Ties”

Understanding the Importance of having Both Open and Closed Networks of Relationships is Essential for Living Through this Time of Transition

All Crises Are Local

At the beginning of the global COVID-19 pandemic, as the world began to shelter in place, I decided to write about what I observed. The first thing I wrote was a short book called All Crises Are Local. It was a critique of what I saw as a failure in the global response to this new coronavirus. I saw it as a systems failure.

A system is an interdependent network of functions within a social or organizational structure. …

COVID-19 is not simply a global health crisis. Public health is one function among many. As a systems crisis, the coronavirus pandemic impacts every person, organization, and community on a global scale. The crisis is impacting the economies of the world, the political cultures of nations, and the social progress that has advanced world-wide over the past century.

The problem is that we tend to see the world in binary (good vs. bad) and linear (one thing follows another) terms.

Problems are not only harder to solve this way, but we can’t see the whole of what a person or situation is. We need to change the way we look at the world.

How the Expansion of My Network Presented a Different Perspective than My Closed Network Did

From my birth until 2014, my world was rather self-contained in what network terminology would call one lacking in structural holes. At that point in time, I began to travel overseas. Over the next seven years, I would travel, mostly alone, to sixteen nations on three continents. My perspective of the world changed. I have written about this perspective as the Two Global Forces.

In mid-January 2020. I heard a story about the release of a pathogenic virus from a lab in China. I did not know if this was true or not. How could I know? I just tucked this little piece of information away in my brain. A few days later I flew to Nairobi, Kenya for a month of leadership training in Kenya, Uganda, and Benin.

After we landed, an announcement was made that five hours earlier, a Chinese national had arrived in Kenya, and was sick with some virus. He was taken into quarantine in the airport’s medical facility. Not knowing what any of this really meant, I tucked away this bit of information in my brain. A few days later, an Uber driver picked me up to drive to a local university where I was to give a lecture to students. On our way back to my hotel, I asked my driver about what he had heard about the virus and about all the Chinese workers working in Kenya. At this point, we were driving on a partially completed cross-town freeway that the Chinese were building. He pointed out that all the construction projects had been closed down and the Chinese workers were nowhere to be found. Another bit of information tucked into my brain.

In mid-February, I flew from Nairobi to Kampala, Uganda. A week later, I flew from Kampala to Cotonou, Benin, through Kigali, Rwanda. At each point of travel, I was asked where I had been, where I was going, if I had been sick, and had my temperature taken. Already, pandemic precautions were being initiated across the African continent. On March 1, I flew from Cotonou to Paris, where my temperature was checked before being allowed to board my flight back to the US. A week later, the global pandemic was declared and public health social orders were instituted.

The Emotional Toll of the COVID-19 Pandemic

As I looked at the pandemic crisis through a systems perspective, my network of relationships that extended around the world provided a broader, more nuanced perspective than what my closest friends and family were receiving here in the US. The social toll of the pandemic restrictions was quickly impacting people, their relationships with loved ones, their friends, their jobs, and the places where they’d congregate in their local communities.

From my vantage point, I saw the emotional toll on people and communities worldwide. It showed many people that they lacked the breadth of relationships known as “weak ties”. These relationships could have provided them with perspective and resources for countering some of the more destructive effects of governmental public health social orders. In other words, our “strong ties” did not provide the access to information and resources because ultimately they were too insular and narrowly focused.

Mark Granovetter describes the “strong ties” of our relationships.

“… the strength of a tie is a … combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (mutual confiding), and the reciprocal services which characterize each tie.”

I observed that the people that I was the closest to were responding differently than I was. With many of them, fear of the virus reigned supreme. It was a traumatic moment for them. First, they were told it would take “two weeks to flatten the curve.” Then it became clear the social orders were going to be with us for a long time. I saw people emotionally pulling deeper within themselves becoming more isolated and distressed.

I observed others who had broken out of their closed networks during the 2016 US Presidential campaign to become supporters of Donald Trump. Their new perspective opened their perspective on the world. I am not making a judgment here, only pointing to the pattern of behavior where someone sees or experiences something that opens their perception to new realities. These friends and family members’ access to information changed as they discovered structural holes that previously did not exist, and that is now being bridged with new relationships and sources of information. Some of these people in spite of pressure from their former closed network of relationships decided to not be vaccinated. Some of them quit their jobs when their employers mandated that they receive the shot.

Those who followed the rules, and did what they were told, felt increasing social isolation from sheltering in place. While Zoom calls quickly became how we worked and related to people, they did not counter the emotional trauma that many people were feeling and are still feeling today.

At this time, I began to hear stories of people catching COVID with debilitating complications. Others told me of family members who were either dying of COVID or died with it. The trauma of loss and profound sadness was taking its toll on people. They retreated further into emotional isolation. Their closed networks were under stress because they grew up in a society that wasn’t under threat by a global coronavirus. Closed systems and networks have a difficult time learning to adapt to change.

I had seen this pattern of behavior before in people, their families, and at their workplace where catastrophic crises disrupted the normalcy of life. The hardship of a loved one becoming sick and within days or even hours dying is quite difficult.

When hope is lost, you stop looking for it. The security and comfort of your place in life become what you cling to. As those physical and relational spaces became restricted, I saw them going emotionally deep within themselves to cope with a change in life that was unexpected, unasked for, and, in many respects, permanently disruptive.

The Networks of Relationships COVID Story

The confinement and insolation of the pandemic have their parallel in network theory. I know people whose circle of relationships is quite small. One person told me years ago that she would be happy with only two or three friends in her life. This is like having a small closed network where everyone knows everyone else, accesses the same sources of information, and never ventures too far beyond the comfortable boundary of their group.

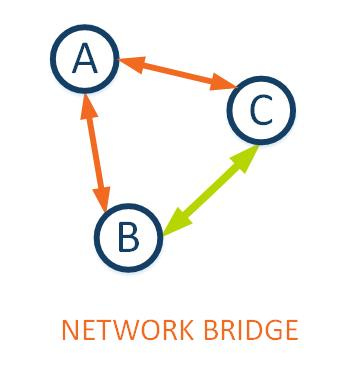

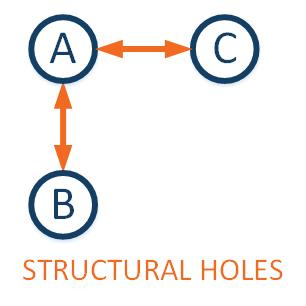

These closed systems have no structural holes. A structural hole is a missing relationship between two people who each know a third. When a structural hole is bridged, social benefits come to all three of those in the network.

When we speak of strong ties, we mean that we are all tied together. We find safety and security there. We not only feel and think the same way, but we may also find ourselves as a group failing to see a larger systems perspective. We live a settled existence of resignation to what happens and mistake biased, insular opinions as trusted expertise.

Many people that I know are rule followers. They do what they are told. They usually don’t question authority. I’m not one of those people. I question everything. It isn’t that I am unwilling to trust people. Trust is very important to me. It is why I am skeptical of all experts. I question them because their expertise is typically narrow and prejudicial towards alternative perspectives. The experts are the ones who complain about misinformation and conspiracy theories. If your network of relationships lacks sufficient structural holes while looking to experts for guidance, then your response to outside perspectives could be similarly narrow and insular.

What you do know matters less than what you don’t know in the midst of a crisis of global proportions.

The social structure of closed networks operates within a set of social, intellectual, and emotional boundaries. Everyone knows everyone else. Everyone reads the same websites, watches the same news shows, reads the same books, goes to the same restaurants, visits the same vacation sites, went to the same schools, and believes the same things about just everything. These closed networks feel safe and secure until the outside world becomes chaotic and there is no answer from within the group for what is happening.

The Return of The Strength of Weak Ties

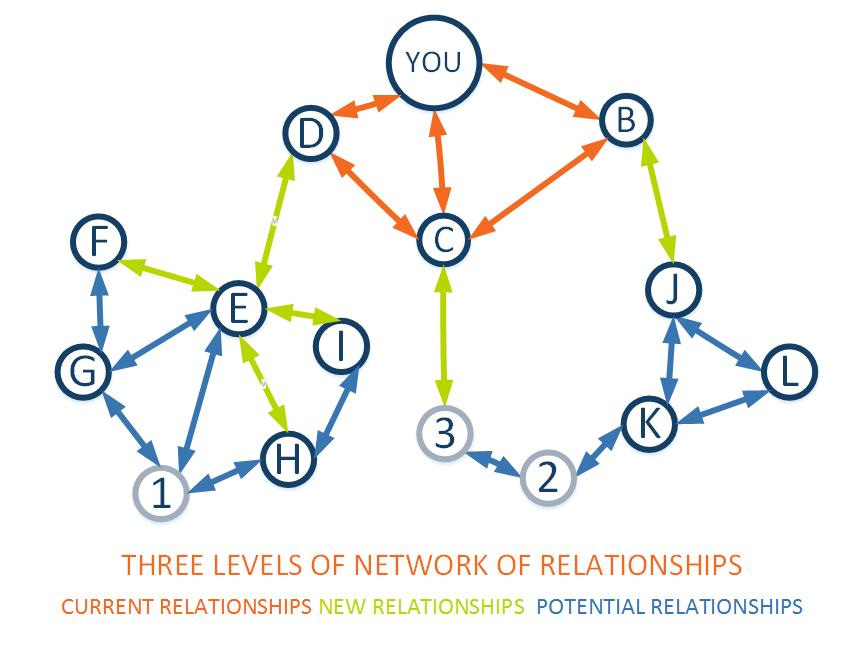

Mark Granovetter’s classic article The Strength of Weak Ties is instructive for us. Let’s look at my diagram of three levels of bridging of the structural holes in an expandable network.

Granovetter sees that the structural hole between B and C and between D and C is never absolute. In a relatively closed network where A knows B, C, and D, there is a real chance that B, C, and D know who each other are, and yet, never formally have been introduced. By this observation, Granovetter believes that there is a bridge that already exists between B, C, and D. They just need a reason to get together. It is only a matter of time before A invites B, C, and D to lunch to initiate a shared endeavor. This is how social capital is created. Granovetter uses terms like triad and dyad to simply identify the relationship between people within a network.

“If we assume that mutual choice indicates a strong tie, this is strong evidence … that in triads consisting of dyads expressing mutual “high attraction,” the configuration of three strong ties became increasingly frequent as people knew one another longer and better … The significance of this triad’s absence can be shown by using the concept of a “bridge”; this is a line in a network which provides the only path between two points … if the stipulated triad is absent, it follows that, except under unlikely conditions, no strong tie is a bridge. … Weak ties suffer no such restriction, though they are certainly not automatically bridges. What is important, rather, is that all bridges are weak ties. “

This technical description points to a simple reality that we all experience.

There are people we know but with whom we do not have a relationship of mutual interaction and benefit.

We go to a school function or a business conference. We meet people. A relationship gap exists between us as a structural hole. Take this thought one step further. Almost everyone in your social media contact list is a structural hole. Until you form a relationship apart from the context of social media, you don’t have a relationship. You only have a connection.

Now, here is how our social media connections create value for us. Every one of those connections constitutes a weak tie with an unbridged structural hole. Every one of them.

Not all of those connections are of equal value. Some of them just replicate who we already are and already know. Others are so far beyond our current network, it is difficult to know how to move from connection to relationship.

As I described above, over the past decade, I have traveled extensively and traveled by myself. Whether it is driving across the US at least once a year or traveling across Europe or Africa, or to China, South Korea, and Thailand, I meet people who broadened my perspective and confirmed much of what I already knew and doubted. Some of those interactions lead to ongoing relationships where we support one another in the work that we do.

Many of those relationships are weak ties that become bridged structural holes with other people that I know. This is what I mean when I say …

Who do you know that you think I should know and would you introduce us?

To personally bridge another person’s structural hole may be the most important benefit to come from expanding your network. It is there that being a person of impact has a global impact.

It is Not a Choice Between Closed and Open Networks, Between Strong and Weak Ties

Throughout this whole series, I have been trying to convince you of one simple truth.

Who you don’t know is increasingly more important than who you already know.

If you focus your relational life only on those who you already do know, then you are restricting yourself to what your circle of relations has already decided is important to know. Your intellectual life will be noted by two patterns of behavior that arise in people during times of chaotic change. Those behaviors are cognitive dissonance and confirmation bias. These forms of behavior both protect us from outside influence and place us at risk for not understanding what is transpiring in our world that places us at risk.

The risk that comes from only having a closed network is the product of a network where all the structural holes have been bridged. This is why Mark Granovetter wrote that “no strong tie is a bridge. … that all bridges are weak ties.” This is problematic in our time because without weak ties to broaden our social and situational awareness, we can find ourselves supporting actions that ultimately bring harm to our lives. Innocence and naiveté can no longer be valid excuses for not knowing the big picture of what is taking place in the world.

Today, everything is revealed. Nothing is hidden. It is only the behaviors of willful blindness that place people in a position where they freely support that which is harmful to them.

Just so that I am absolutely clear.

We need our local community networks of relationships.

We need to focus on how we talk to one another and care for our neighbors. At the same time, we need to develop relationships with people who don’t live where we live, don’t think as we think, and whose perspective broadens not only what we think of as reality, but more importantly the value of our lives in the world today.

We also need a global network of weak ties that offer plenty of structural holes to be bridged by new relationships.

Where do you start?

1. Identify people in your community that you have been introduced to but who you have never had a one to one conversation. Invite them to coffee and just talk about your life experience. Then ask,

2. Who do you know that you think I should know, and would you introduce us?

3. Work through your initial list doing #1 and #2.

4. Do this for the next three months. Keep a list of each person with whom you met, and mark down one thing you heard from them that you did not know or was new information to you.

5. Lastly, ask the Five Questions That Everyone Must Ask. Ask them in the context of what you are learning and how your perception has changed.

Building networks of relationships that are both open and closed will guard us and advance us forward as we go through a time of great change. If you want to know more, ask your question in the comments so that others who share the same question can benefit from the bridging of the structural hole that exists between us all.

Interesting application of these concepts to the covid situation.