The Science of Networks of Relationships

How understanding diffusion theory, the strength of weak ties, and social capital can energize our life, work, communities, and sense of purpose for impact.

This post is a continuation of my post, How Global Networks become Local Networks of Relationships.

The Ideas behind Networks of Relationships

I want people to understand how networks function in a practical sense. We all deal with digital networks. Wifi, Bluetooth, Personal Hotspot, and cellular phone networks. We live with them even if we don’t understand them.

There are also human or social networks. Your family is a network. This is especially true if three or four generations of your family live in close proximity to one another. Over the past few weeks, I’ve been traveling to visit aunts and cousins. Next week it will be my kids and their spouses. Our neighbors form another network. Our business coworkers another. We are surrounded by networks. And yet we are mostly unaware of how they work.

There are three ideas that I want to share with you in this post related to the function of networks of relationships. The first is an idea called Social Capital. The second two go together as The Strength of Weak Ties and Diffusion of Innovations theory. It is important to understand these concepts to fully appreciate the importance and value of creating a network of relationships.

Social Capital

This idea, social capital, came to public awareness twenty-two years ago through a book by Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Putnam writes.

“The central premise of social capital is that social networks have value. Social capital refers to the collective value of all “social networks” [who people know] and the inclinations that arise from these networks to do things for each other [“norms of reciprocity”].”

The value of our relationships is like an economic asset. Think of social capital as the purpose of your smartphone. You are connected to all sorts of people and groups. As a result, you have access to information that if you did not have a smartphone or computer would not be available.

Social capital is not a neutral asset. It has value and at times misplaced value. Access to information and knowledge is valued based on its purpose. You link to persons you know to gain perspective and information. You call your neighbor to confirm that the picnic is at 4 pm and to see if you need to bring any extra food. At that moment, the connection is like a bridge between two points of land. Not only the offer to help, but the help itself is the social capital that networks generate

You have heard the saying, it is not what you know, but who you know that matters. This social capital perspective is only partly right. It is not simply who you know that matters, who they know that matters. Social capital is not just one degree removed from you, but as many as necessary. Looking for a job. You contact one person, who sends you to a second, who sends you to a third. This is the network effect of social capital.

Social Capital in Real Time

I have frequently told the story about when our family moved to a new community. My plan was to start my consulting business. I came with three contacts other than an aunt and some cousins. I approached the three contacts who had been referred to me and told them about my interest in developing leaders for local communities. I would say to them, “Knowing what you now know about my purpose, who do you know that you believe I should know, and would you introduce me?” From those three contacts, came over 30 new contacts and their phone numbers. I repeated the process with those referrals and eventually, my first consulting contract was secured.

Through this process, a retired business executive became my mentor. One day, he invited me to lunch to introduce me to a man who would later advance my work as much as any person during my career. He was the president and publisher of the local newspaper and a community leader in support of education. He asked me to be his co-chair for an education task force formed through a community visioning process. A year later, I joined the paper as a volunteer community columnist. It was my first writing gig. Then three years later I was hired to write a twice-monthly business leadership column. He had me twice speak to his top 50 managers, and later as he transitioned to the company’s headquarters, we worked together on a couple of projects to support young professional journalists. Through the network that I created as I entered a new community, the social capital that emerged from it set the stage for the work that I am doing today.

Network Brokerage and Closure

Ronald Burt is an expert on the specific aspects of network science related to social capital. His work, captured in three books, Structural Holes, Brokerage & Closure, and, Neighbor Networks, forms the perspective that brings you here.

Social capital is the contextual complement to human capital in explaining advantage. Social capital explains how people do better because they are somehow better connected with other people. Certain people are connected to certain others, trusting certain others, obligated to support certain others, dependent on exchange with certain others. One’s position in the structure of these exchanges can be an asset in its own right. That asset is social capital, in essence, a concept of location effects in differentiated markets. **

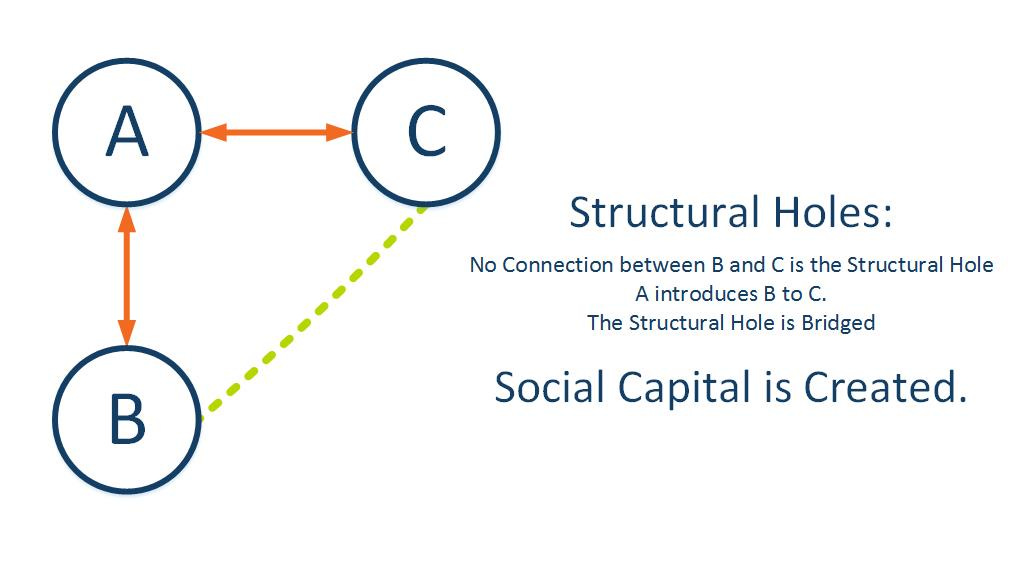

To understand Burt’s perspective, let us explore a simple example.

You (A) know two people (B & C) who don’t know each other. You are the connecting point for them. Your friend B has a job opening for a very specific skill-set and experience. Your friend C has lived in the community all his life. He knows everyone. You make the introduction. Friends B and C meet. Friend C activates his network to find the right person for Friend B’s job.

There is a structural hole that not only exists between A’s two friends but also between all those people that Friend C knows that Friend B doesn’t. Friend A has a competitive advantage over B and C as he contributes to the creation of the social asset. The asset value of these relationships exceeds the value of finding a person to fill the job. There is now experience and with it trust, and other opportunities waiting to expand the asset value of their network of relationships.

This is precisely how I envision networks of relationships functioning to define the future of local communities. It starts with one person or two connecting with another or four or five to establish relationships of trust and mutual service in the context of their life, work, and community.

Structural Hole Theory

Structural Hole theory informs social capital, but it is really a theory about competition. Burt describes.

The structural hole argument has four signature qualities. First, competition is a matter of relations, not player attributes. Second, competition is a relation emergent, not observed. Third, competition is a process, not just a result. Fourth, imperfect competition is a matter of freedom, not just power. ***

Ron Burt is describing competition in different terms than we normally find it.

Competition is not about being a player with certain physical attributes; it is about securing productive relationships. … Competitive is an intense, intimate, transitory, invisible relationship created between players by their visible relations with others. … The social structure of competition is not about the structure of competitive relations. It is about the social structure of the relations for which players compete. The structural hole argument is not a theory of competitive relations. It is a theory about competition for the benefits of relationships. ***

See what Burt is doing? He is reversing the traditional view of competition to gain power to competition to gain the value of relationships. The stronger the competition the greater social capital is developed.

The Hidden Strength of Networks of Relationships

Most of us would probably say that the strength of our networks are with those people who are the closest to us, our friends, co-workers, and family. The closer they are the stronger we are. In one sense this is true in terms of a social unit, like a family or an office staff.

But a network is different. Mark Granovetter has studied this phenomenon.

“Most intuitive notions of the “strength” of an interpersonal tie should be satisfied by the following definition: the strength of a tie is a … combination of time, emotional intensity, the intimacy … and the reciprocal services which characterize the tie.” ****

In looking at a network, we are interested in communication, and connections diffuse information quickly and broadly. If everyone in a network knows one another, everyone assumes that everyone already knows what you know. However, in a more diffused network of weak ties, information travels through the network more quickly because there is an assumption that the people further away from the center of the network or the origin of the information do not know it. Granovetter explains.

“Intuitively speaking … whatever is to be diffused can reach a larger number of people, and traverse a greater social distance … when passed through weak ties rather than strong. If one tells a rumor to all his close friends, and they do likewise, many will hear the rumor a second or third time, since those linked by strong ties tend to share friends. If the motivation to spread the rumor is dampened a bit on each wave of retelling, then the rumor moving through strong ties is much more likely to be limited to a few cliques than that going via weak ones; bridges will not be crossed.” ****

If you start a business, thinking that all your friends and family will be your patrons, then your business will have a hard time succeeding. Because every enterprise is dependent upon finding new customers. Diffusion is the spreading of information as far out as possible from the center where your business exists.

To understand diffusion, we need to turn to Everett Rogers whose book Diffusion of Innovations pointed the way to how new ideas become rooted in a new context. Rogers describes it.

Diffusion is the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among members of a social system. It is a special type of communication, in that the messages are concerned with new ideas. Communication is a process in which participants create and share information with one another in order to reach a mutual understanding. … diffusion … (is) … the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system.” *****

A network of relationships as I conceived it is a social system where people gather for a particular purpose to communicate to their wider networks information that they feel is worth them knowing. The strength of weak ties in a diffusion process is that the information is moving outward away from the center of the network.

Albert-László Barabási’s description of Granovetter’s idea is helpful.

In The Strength of Weak Ties Granovetter proposed something that sounds preposterous at first: When it comes to finding a job, getting news, launching a restaurant, or spreading the latest fad, our weak social ties are more important than our cherished strong friendships. As he put it, the structure of the social network around an ordinary person, whom he calls Ego, is rather generic. “Ego will have a collection of close friends, most of whom are in touch with one another – a densely known clump of social structure. Moreover, Ego will have a collection of acquaintances, few of which know each other. Each of these acquaintances, however, is likely to have close friends in his own right and therefore to be enmeshed in a closely knit clump of social structure, but one different from Ego’s.” ******

If I look at my LinkedIn network, there are currently about 2000 Connections and 5000 Contacts. Granovetter’s perspective of strong ties describes less than ten people from the LinkedIn lists. However, if I did the same review of my Facebook network, the number of close friends and family is much greater. These social media platforms, therefore, serve different purposes.

LinkedIn is a network of weak ties. Facebook is a network of strong ties.

We can speak of this in terms of physical location. More of my Facebook friends live near me and we have interaction with me at local coffee shops, churches, and family gatherings. Most of my LinkedIn connections are global, spread across this great, wide planet. In both networks, there are those who are close to me and those who are remote from me. Their location can be geographic, institutional, or relational. They can be divided between those we know because we encounter them in space and time and then those we encounter in the digital world of virtual time. They all matter, but in different ways. Those who are closer, relate to us in the wholeness of our relationship. Those who are more remote relate to us in a more narrow context. The reality for me as I suspect for many of you is that I value all of you because whether our ties are strong or weak, the sharing of our stories and our purpose is how we diffuse the information that we believe is important to the world. The better we are at it, the great the asset value of our social capital.

Two Global Forces of Weak Ties

Having been influenced by Putnam, Rogers, Granovetter, Barabási, and Burt over the past three and a half decades, their insights influenced my formation of the Two Global Forces framework. For those who are unfamiliar with this idea, there is the global force of centralized institutions of governance and finance and the global forces of decentralized networks of relationships. A fuller description can be found here, here, and here.

We are all local people whose relationships where we live matter. These are the people we are close to, our family, friends, and coworkers. Here in our local surroundings, we see the most immediate impact from the leadership initiatives that we make. This is where we invest the bulk of our lives to make a difference that matters. For us, in this sense, all crises are local, even the most global ones. These represent our strong ties.

Yet, at the same time, we are privileged to live in a global world. Many of us have had opportunities to travel throughout the world. We develop friendships with people who are as close or closer than those at home. In many ways, those relationships are the bridge between the strong ties and the weak ties. They are the source of social capital that brings peace and understanding to places where people are divided.

A way to understand the social capital landscape of the Two Global Forces is to see that our global network is filled with structural holes awaiting to be bridged. Our local network is tight and densely packed with fewer structural holes. As a result, it is more difficult to develop the social capital that is needed.

Ron Burt describes this distinction as the difference between direct access to structural holes and indirect access. It is the difference between a direct relationship with someone and an indirect or virtual one. The key is to recognize the value of both and work to connect them together.

Why This Matters To Your Network of Relationships

If your network is just strong ties, you have a club. If your relationships are mostly weak ties, you are a peripheral figure who only connects through likes on a social media page.

The purpose of a network of relationships is to bring people together to create impact in a specific way. There must be a purpose. If you only gather to chat, then you will become bored. If however you articulate a reason why your network has a purpose, and each member begins to share that message to their network of both weak and strong ties, people will begin to notice.

When I published my first book, Circle of Impact: Taking Personal Initiative to Ignite Change, our marketing plan failed because it was too focused on MY strong ties. Because of that failure, I learned about reaching out beyond my own network to find new people to know. This is why I am writing on Substack. I am seeing progress in growing my audience. Thank you for contributing.

My Next Step

Now, the next phase of my diffusion of ideas about leadership is being readied as I prepare to start a podcast. This podcast, The Eddy Network: a global conversation for local leadership is going to be built by utilizing my weak ties and the weak ties of others. This is a grand experiment that I invite you to join in. I am looking to interview people that you think I should interview. I have an extensive list to begin and will begin recording later this month.

How You Can Help

In the comments, tell me “Who do you know that you think I should know, and why should I know them.” Give me one strong indicator that they have something to say that can make a difference that matters.

* Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community

** Ronald Burt, Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital.

*** Ronald Burt, Structural Hole: The Social Structure of Competition.

Ronald Burt, Neighbor Networks: Competitive Advantage Local and Personal.

**** Mark Granovetter, The Strength of Weak Ties.

***** Everett Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations.

Ed Brenegar, Circle of Impact: Taking Personal Initiative To Ignite Change.