Time and Reality Sabbatical

A Year Later in Time and Reality is Beautiful

First Published as Writing about Time and Reality - 2022-2025

Updated with a new title, February 1, 2026

Time breaks over Morning in the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming

In February of 2025, I stopped the progression of time. I abandoned a writing project that I had been working on for several years. I decided to take a sabbatical from writing.

I was thinking about Time and Reality in the context of my series of essays, The Spectacle of the Real.

Spectacle or simulation culture was destroying time.

I realized that if time didn’t matter, and I know people, many people who tell me that the present is all that matters to them, that society could collapse and it would be just another empty “Breaking News!” “This Changes Everything!” media meme.

For many people, the Past is a painful memory of failure, abandonment, or abuse. I can understand wanting to put those memories out of your mind. I can also understand that for many people the Future represents a threat of loss and embarrassment. The Present has none of this. We wake up every morning with a new start.

Does this mean we are always starting and never finishing?

My sabbatical lasted four months. I started by reading T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, and William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. I read the works and then listened to them as I drove West to Wyoming in June. Reading and listening are different. You get a different scope of the story.

I began to explore Time and Reality in January with a series of posts called Starting Point. Increasingly, I saw that Time was not a collection of discrete moments. It isn’t measured by the hands on a clock or even the passage from night to day and back to night. It is more dynamic than that.

The Continuity of Time, as I came to describe it, meant that the Past mattered because it flowed into the Present and out of it to the Future. There is no escaping the Past. And there is no certainty about the Future. It’s all connected.

Late in the sabbatical, as I traveled West to Wyoming, I produced a series of podcast episodes reflecting on what I was seeing.

Early in the process, I realized this topic was the focal point for the rest of my work. Leadership had been for 35 years. That moment was complete, not necessarily done, but complete in the development of my perspective.

The Anniversary of the Sabbatical

Today, February 1, 2026, is the anniversary of the start of my sabbatical. I look at the past year as a generation in time. What transpired during that year has led to what will be the next generation of my thinking, my writing, my podcasting, and my life. Each of those is an open process of discovery … in time through the experience of reality.

Three major themes have emerged. They are not necessarily new themes for me, but they take on a different significance.

Generational Memory

Generational memory represents the continuity of time. Not only are we always in relationship with the past, and its many generations, but as creators of generational memory, we are providing future generations with a context of understanding that spans time.

In my family, I am the oldest born of the blood of my father’s kin. My mother’s sister, my aunt, will turn 99 years of age next month. She is the oldest of my grandparents’ kin. I have cousins from my mother’s three sisters, who are older than me. When we are together, the past is remembered, and the future beheld.

Family as a social institution is a vehicle for generational memory that moves from the Past through the Present into the Future.

The loss of the institution of family in the modern world makes it much more difficult for people to know who they are and how they exist in Time and Reality.

The Cultures of Simulation and the Real

I’ve written quite a bit about this subject recently, especially in my post, Held Hostage in a Luxury Hotel: The Hegemonic Character of The Culture of Simulation.

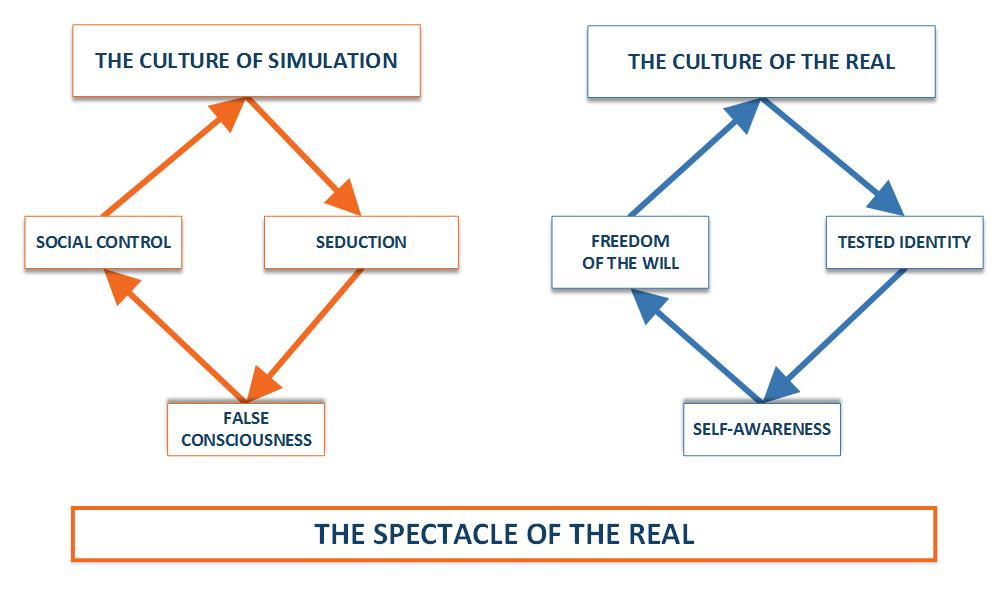

This difference between The Culture of Simulation and The Culture of the Real can be visualized in this diagram.

The simplest way to describe what I see here is that simulations are simulated realities or false realities. In effect, they are a type of lie intended to seduce us into believing that we can live without the consequences of reality.

In effect, The Culture of Simulation is a control mechanism.

We are seduced to believe something that is a lie. Once the lie takes over our belief system, we are controlled by a false consciousness that depends on the creators of the simulation to keep lying to us.

Submit the simulation to scrutiny, and either we recognize its unreality or hyper-reality, or we decide to continue to lie to ourselves and others because we are so mentally and emotionally captured by the seductive power of the simulation.

The alternative is to embrace consequential reality. Recognize that there is a reality that exists beyond our control. See that if we treat reality with respect, it can provide a pathway to fulfillment and genuine freedom.

I recently had a conversation with a new friend about fear, and how we face it. I realized as I described various situations that I have been in during my life that many people would have responded to them in fear. However, while I never used this term before this conversation, I recognize that I am rather fearless in the face of reality. I respect the consequential character of reality. I understand its threats and dangers, and act accordingly. To fearless doesn’t mean that I do not have fear, only that I choose not to let it become an obstacle to my daily existence.

If you are detached from reality, which I suggest is a way of talking about mental illness, you have a difficult time escaping from the control that it has over you. I know physical and emotional trauma can be devastating. I also know that it can be overcome. The key is to respect the consequential character of reality, and find peace with it.

Love as The Blood of Reality

Beginning in the 1970s, as a university student, I began to work with adolescents. Some aspect of my work has always been related to young people from ages 10 to 40. It has been a consistent issue through all these decades and different generations that older generations feel a certain proprietary ownership of what is true and important.

It has also been true that younger generations tend not to appreciate the wisdom that older people have. Just an observation that our generational differences matter.

I hope you see the gap here. In effect, older people believe we know things that are important for younger people to know. What we tend not to communicate is how we came to see the world as we do. In many respects, we lack a self-consciousness of our own learning in life. We know what we know and freely share it with anyone who will listen.

We don’t understand that younger people live off questions more than they do answers. They are living at a time of discovery.

During my sabbatical, I talked with people of all ages. I intentionally sought out young adults in their 20s. I shared with them my perspective that I have shared with you above. When I describe their situation, “answers to questions never asked,” their response was uniformly, “Oh, YES! That’s exactly right.”

As a result, I decided to write a novel with the title, Answers To Questions Never Asked, that would capture this dynamic. It will be published in serialized form later this year.

The story is about a boy, the youngest of six children, and the youngest by six years, whose parents die in a plane crash when he is three years old. He and his siblings are raised by his father’s parents. This grandfather is a decorated military veteran having served during both World Wars and on General Marshall’s staff in the relief of post-War Europe. His other grandfather, his mother’s father, is a U.S. senator. These two men of great influence in his life in effect define what it means to be an adult.

From the grandfather who raised him, he learns how to live on a farm and in the woods. When he is 18, he goes off to college. In his first class in his philosophy course, the professor says the following.

There is no Past. Nor Future. Only the Now.

Everything that was in time has vanished into simulation.

The statement confuses the young man. During a mid-semester return home, he tells his grandparents what his professor said. The following conversation comes from chapter one of Answer To Questions Never Asked.

Answers To Questions Never Asked - Selection - Chapter One

The Defining Question

When Grandfather finally responded to my stories of my professor’s teaching, he wasn’t interested in what he taught. The idea of simulation seemed to make sense to me. Grandfather was more interested in who my professor was.

“What does your professor love?”

“I guess he loves philosophy and teaching university students.”

“No. That isn’t what I mean. That is what he does for a job.

What does he love? What does he give his life to? What is he willing to sacrifice to preserve and protect because he loves it?”

“Ask Plato, Aristotle or Augustine, what they love. They could tell you. Come with me.”

Grandfather led me out of his study. We crossed the field behind the house to where the river cuts through the valley where we live.

He pointed to a mountain in the distance that must have been 10 miles away.

“When I was a child, living here, where our family has been for generations, I’d fix a sandwich, fill a bottle with water, and I’d walk to the top of that mountain. You and I have hiked that mountain many times. But you never did it on your own initiative.

The first time, I did it because I wanted to see if I could do it. I was only 10 years old. I got to the top and sat and ate my sandwich. I climbed the fire tower, from which you could see for at least fifty miles in every direction.

There is something to rising above every situation. We gain perspective. We can see how things relate to one another. Up there, you can see how the river winds around the farm.”

From the edge of the river, in sight of the mountain, Grandfather taught me his philosophy. It was more subtle and less abstract.

‘The first time I climbed the mountain on my own, it lit a fire in me. From then on, I wanted to accept other challenges. I ran away from home and joined the army so I could go fight in France. My grandfather knew what I was doing. He made arrangements for me to serve. After I disappeared, he told my mother and father what I had done. They didn’t like it, but they didn’t keep me from doing it, either.

When I enlisted to go fight in France, I did so because I thought that it was something I was supposed to do. The idea of service had been a family tradition. There was a kind of romance to serving your country. It was that way until the battle began. There were no illusions of romance in the trenches of eastern France. Kill the enemy before they kill you was the philosophy that kept us alive. Death was everywhere you turned. If you were not there, how can you talk about it? The sound of battle still rings in my ears. I will never forget those months.

Here is what I want you to understand, Robert. The romance of war is a simulation of love. It can fill a man with a sense of purpose and mission. At the end of the day, it is about killing or being killed.

War is hell. It challenges all the false notions of heroism and nobility. We should honor those who serve, but not because they love war. The officers back in the command center may believe in the romance of war. The soldier on the field of battle doesn’t. He is thinking about getting home to the family he loves. War either destroys the man or it completely focuses attention on what is essential in life. What is essential is what we love.”

The seriousness in his voice struck me. We were not talking about ideas, but about something deeper.

He then said to me.

“When your parents died, it was a greater shock than all the deaths that I saw in two world wars. It hit your grandmother particularly hard. I still see her looking out the kitchen window across the field. I know she is thinking of them. The sense of loss never leaves us. We must carry on. We have to keep on living. But life changes when you lose someone.

I’d like to know what your professor loves because I want to understand what he sees when he stares out the window in his kitchen. Is he seeing a loved one he has lost? Is he reliving an action that he regrets having done? How does this idea of simulation remove the pain of death and loss?

I want to know what he is willing to sacrifice to preserve and protect. Whatever that is, it is what he loves.”

My mind was racing. Could it be that my professor loves the simulation? Or is it a screen to hide behind? I was more confused than ever.

At that moment, we heard Grandmother calling us across the field to come to lunch.

As we turned to head back to the house, Grandfather said, “When you get back to school next week, go see your professor. Tell him about our conversation. Ask him, “What do you love?”

Reflecting upon our conversation on the ride back to school, I thought, “What do I love? I wondered if I was too young to know.

As the story progresses, Robert, the protagonist, realizes that he is caught between the influence of his grandfathers and his professor. He with draws from school and begins a search to understand the deaths of his parents, and the questions that he should be asking to shape the life that he can live. As the writing carries the story, I only know where it going as I write each day. I am surprised as much as those who are my readers. Soon, I’ll present the book in serialize form for others to read and respond to the story that I realize has a universal character, regardless of time.

Now, on the anniversary of the beginning of my sabbatical, I realize that the question of love, not romance, affection or desire, but love that invests in that which is essential, is beckoning us to invest a reality where love matters.. Ultimately, this is the question that Robert, too, will have to answer.

All the posts and podcast episodes on Time and Reality can be found in the original version of this post, Writing about Time and Reality - 2022-2025.