If you have done well in your career, become successful, have gained notice for your expertise publicly, and moved through the circles of the rich, famous, and powerful, you may believe that this grants you a certain status as an expert.

Out of these experiences we derive our personal philosophies of life. They take the form of stories that we use to advise others. Consequently, many of us will write books, develop speaking careers, and coach others who want to be experts like us.

As one of these people, being recognized as an expert in my field has not been as important as the weight of responsibility. I value what I’ve learned. And in a very counter-cultural move, I resist the commodification of my advice. I tell people that I chase relationships rather than numbers.

For me, it is not a matter of what people think of me but of what I think of myself. My integrity is the expertise that daily claims my attention. Part of that burden is realizing that what I don’t know is far more weighty and humbling than whatever I have learned over the years.

The first rule of expertise, therefore, is never to take yourself too seriously.

The second is to develop yourself as a contributor rather than a critic.

The Critic as Expert

Social media platforms offer a rich diversity of advice. Those who master the craft of social media are called “influencers” because they influence our consumer buying habits. They are the true experts of the virtual world.

Consumer choice is more than the products we purchase. Influencers affect choices about lifestyle and socio-political ideology. Their influence drives a desire for acceptance and connection.

As influence has become the currency of digital culture, traditional leadership has faded in relevancy as it has become marginalized. The disintermediation of institutional power has been replaced with influence which is more difficult to measure. Numbers of followers measure attraction which is a weaker form of influence.

With the rise of digital culture, institutional authority was severed from accountability. (To understand this better, see my short book, Where Did Trust Go? Restoring Authority and Accountability in Organizations). This paved the way for the professionalization of expert opinion. How do we measure expertise in a world where there is no real, tangible connection between the expert and the person influenced by. them?

I’ve watched these trends closely for 40 years. Even before the digital age emerged, confidence in leaders was declining, and it continues today. It is a function of both the leader himself or herself and the transitions that we are witnessing in the world.

I identified this as The Spectacle of the Real phenomenon. The dilemma that it creates is as I describe,

“We are drawn to the image on the screen of these "experts" having something to say that is meaningful, hoping that at some point some sense of the moment will be revealed, bringing reality into view.”

The full quote captures the context of expert opinion, criticism, and influence.

“Fueled by a 24/7 news cycle, actual news - a statement of "facts" that an event, an accident, a death, an agreement, a visit or something has taken place, described in the traditional journalistic parlance of "who, what, when and where" - is transformed into a spectacle of opinion and virtual reality driven by the images of faces speaking words of crisis, fear, and self-righteous anger. Televised analysis - more important than the "facts" of the story- drives the news through the ambiguity of the visual image and is its source of validation.

Imagine a gathering with family and friends, catching up on the news of each other's lives, and the conversation is like the panels of "experts" who fill televised news each day. No one intentionally chooses their backyard barbeque guests to mirror the political divisions of the nation. That would be boring, tedious, and just inhospitable and unwelcoming.

These televised events aren't conversations seeking truth, but, rather, people talking at and past one another in a game of leveraging images for social and political influence. We are drawn to the image on the screen of these "experts" having something to say that is meaningful, hoping that at some point some sense of the moment will be revealed, bringing reality into view.”

All of us are looking for some assurance or some ground of truth so that we may know who we are and what our life’s meaning is. The problem is that without a direct relationship with the advisor or therapist, we may never truly know anything for certain, except that everything is uncertain.

The debate about conspiracy theories, misinformation, disinformation, and malformation is precisely one about the inability to know anything for certain. This is why the debate is particularly political. While everyone has an opinion about this politician or that one, or this policy or another, none of us really knows what is taking place outside of our view. This is why social influencers are so important in political campaigns.

The problem is that much of the criticism or advice we are given is a projection of the influencer's inner life. I know this is a rather obvious statement. After all, human creativity begins within us, forms, and then is expressed outwardly. This is an authentic representation of the person.

However, in the arenas of social and personal conflict, our espoused beliefs are often in contradiction with our feelings. We look to experts for reassurance. When those experts are principally critics, their statements deflect attention away from what is true of the critic onto some convenient personality that is the focus of critique.

We all pass judgment on people and situations, criticizing them for the very thing that is true of us. These contradictory expressions are made with great passion hiding our true selves. Whether to save face or not be ostracized by society, we say the opposite of what we truly believe. We do so, by seeking validation and connection with some perceived social grouping that gives us a sense of standing in the world.

The quote above from The Spectacle of the Real describes this pattern of behavior by the media. The passionate hatred for one’s political opponent reminds me of the story told during one of my sermon classes in seminary. The story goes that in the sermon text for the Sunday service, the minister puts in bold type, “Speak forcefully. Weak analogy.”

The Problems of Following Advice

Three problems emerge from our uncritical following the advice of experts.

The first problem is that it is impossible to diligently and faithfully follow the advice of all those people.

The underlying mindset of the advice machine is that every practice and discipline is replaceable with another comparable practice or discipline. Advice is a commodity measured by social media numbers.

Advice viewed from this perspective is not holistic. Advice treated reductionistically fails to encompass the whole of the human experience. Advice that demands a total, singular focus will end up feeling inadequate because it doesn’t cover all the needs that we have for advice.

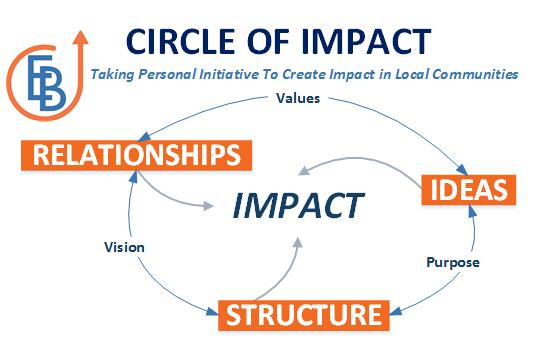

Instead of advice or inspiration, we need tools that allow us to adapt to the various contexts we encounter. Without realizing it at the time, my Circle of Impact model of leadership developed as a universal tool that could be applied in any situation. The advice embedded in the model is simply “think for yourself.”

The second problem is that we don’t know how to think about context.

When we only see in parts, not wholes, we lose touch with the context of our lives.

When I meet someone, like on my podcast, I typically ask them, “Who are you, and what do you do?” It is a question of being and doing. When I say, “Tell us something about yourself,” I want to know something that the person feels is important for me to know about them. They are describing to me the context that they live in.

Context is a challenging concept to grasp. It is more than where I am physically present. It is more than my familial, genetic, academic, national, and career history. It is more than what captures my attention at the present moment. It is more than my connection to friends and coworkers. It is more than my perceptions of life and reality.

This is the hardest part of self-improvement because it is always changing. If our awareness is limited to the specifics of our lives, we can miss things that are also important. We can place our trust in people or organizations whose advice may sound good but is advice poorly suited to the context of our lives. The only way we really know is to broaden our understanding of context.

How do we do this? We become curious about other people and situations. We begin to see that much of the advice we receive feeds a sort of low-grade narcissism where we are constantly focused on our own self-improvement. This is why I believe we need to ask the context question by asking what difference will this bit of advice make in the context of my relationships and work.

The third problem is the mechanistic mindset.

I used above the phrase, “the advice machine”. As a machine, it convinces us that all facets of our lives are interchangeable. When advice tells us that we can be anything we want to be, we love to hear that optimism. But it is bad advice. We can’t be ANYTHING. We can only be what we are. We can learn new skills, develop latent talent, and change the context in which we work. We are still the same person.

I’ve known people who have followed this advice. They are following a vision or a dream. They are sacrificing everything to follow that dream. Then, sometime in their 40s, reality sets in, and they realize that for all the success that they have found, they are not fulfilled. Happiness for them is fleeting.

One of the most powerful pieces of advice concerns the pursuit of a dream that would make them happy. Even in achieving their dream, they realized that something was missing. As a result, they start over, wiser, and more humble, realizing that there is more to life than the pursuit of our goals.

We can see that advice of the minimalist type and of the maximalist kind follow an essentialist perspective. This bit of advice is the essential path to success. Both are difficult paths to follow because they are meant for a specific purpose that may not encompass the whole of life.

My Advice for People Seeking Advice

My advice is more of a set of suggestions. Do them or not. You decide.

Be curious.

Read broadly.

Think critically. Not every opinion leader has something valuable for you. There is no obligation to listen, do, or believe in any advice you are given. Think for yourself.

Be open to what appears before you.

Be willing to make mistakes. And apologize when necessary.

Learn something from every encounter with a book, speaker, podcast or encounter with a person. Act on what you learn as soon as possible.

Keep a journal. Write down something every day, even if it is one word.

Share your thoughts in conversation with people you know and are just meeting.

Ask in every situation, “What is the impact that I want to come from this encounter?”

Lastly, give thanks for the experiences that you have.

My Advice for Experts

Be humble. Don’t take yourself too seriously.

Be gracious.

Believe in people. Do not entertain cynicism.

Change your mind often.

Learn new skills.

Travel to places where no one knows you.

Admit your failings.

Listen more. Talk less.

Write daily.

Say thanks every day.