Leadership and the Culture of Simulation.

Series Two of Reality, Leadership and The Spectacle of the Real

Part One

The Problem of Leadership

Modern conceptions of leadership in organizations are THE vehicle for the culture of Simulation in our time. There is no more exaggerated and misunderstood topic. When I began to study the world of leadership in the mid-1980s, little did I know that it was preparing me to see this culture of Simulation that I wrote about earlier.

The problem isn’t simply that our conception of leadership is the triumph of the marketing of heroic and superlative figures. It is also the entry point for how organizations end up living in a dream world of unreality. The following account of a project shows how simulation is a way to hide from reality.

Too Little Too Late

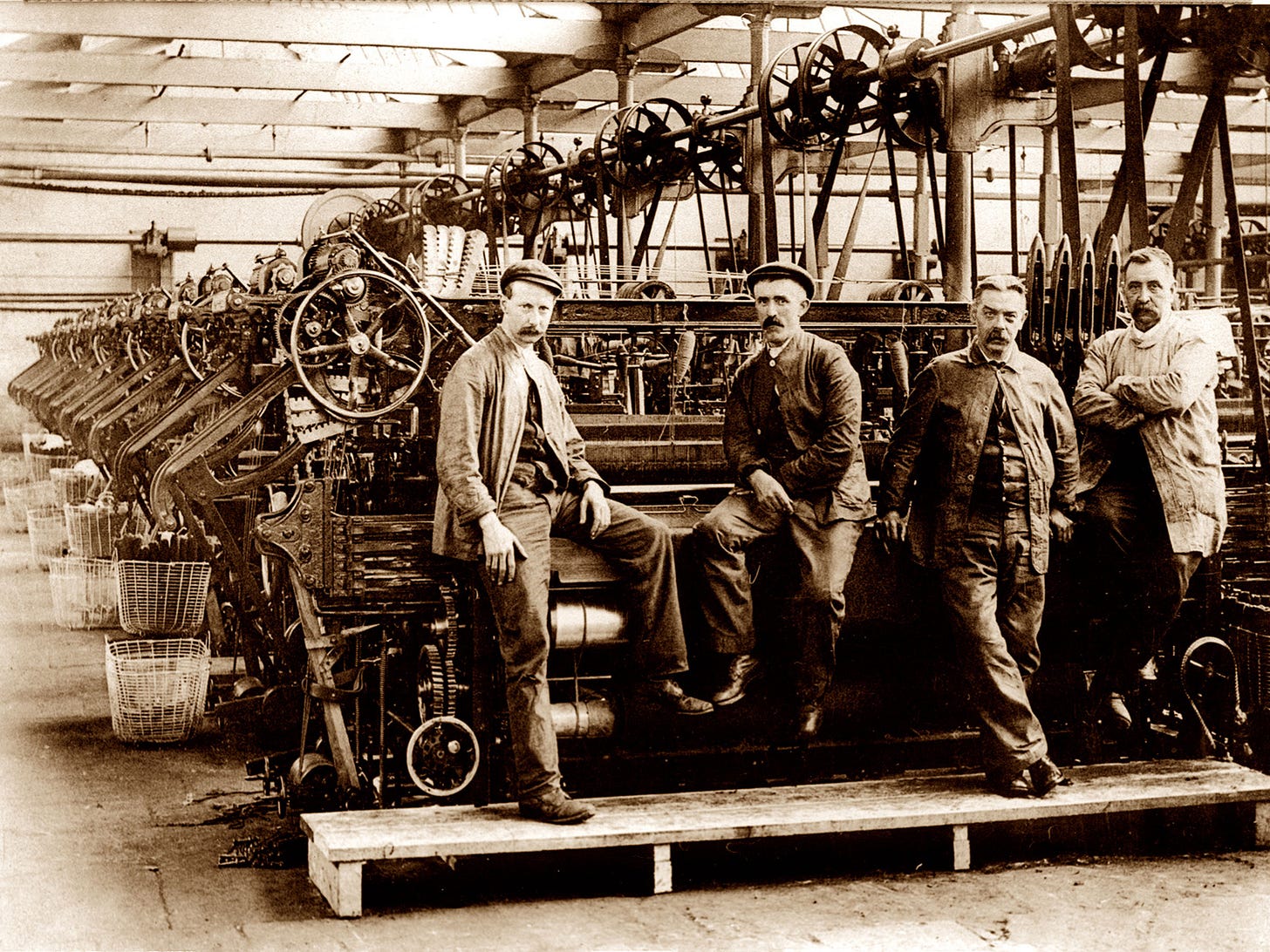

In 2000, I was asked to join a group of consultants as a process facilitator to address a problem that a hosiery mill was having. This mill had been in operation since the early 1940s. It was family-owned and operated. The founder, still alive, came to the office every day. His son was the current president, his nephew was the operations manager, and his son-in-law, the sales and marketing manager.

The company had been losing money since the early 1990s. What explains a company losing money that doesn’t address this fact.

Are they oblivious?

Are they overly confident that things will magically turn around?

Is it simply that fact that no one knew what to do so they kept doing what they had always done.

My assessment is that each reason operated simultaneously which brought this company to the point of closure.

The operations manager finally put his foot down and forced management, the family, to address the elephant in the room. He had the most direct experience of watching the system fail. He forced the family to stop paying the founder a full-time salary. Then, he forced them to address the manufacturing process.

Our Process

Our team was brought in to conduct a review and provide recommendations for change. On the team were a data specialist, a consultant specializing in change processes, another consultant trained in a continuous improvement process for manufacturers created by Eliyahu Goldratt called Theory of Constraints, and me who was the facilitator of the communication between the team and the company.

The mill’s manufacturing process for making socks consisted of 17 steps or stations. At the time of our project, it took six weeks to make and ship a pair of men’s socks. You heard that right. Six weeks! The system had not changed in sixty years. They hired and trained for each station. That person would spend eight hours each day creating product inventory for that particular station. In other words, each station had a backlog of inventory. If you work in manufacturing, you already see the problems in this system.

Applying the Theory of Constraints Model

It was clear that change needed to happen. In order to know what to do you have to ask the right questions. Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints is a change process that focuses on inventory control.

“The rate of turnover or usage of inventory is an excellent measure of the performance and rate of change of manufacturing companies.”*

Seeing this situation, I wondered how long it had been since their inventory turned over. Imagine not turning your inventory over for a decade instead of once a month. As a result, using the Goldratt system, we addressed the highest leveraged constraint of the company’s operation. Following Goldratt, we asked the following questions.*

What to change? (Where is the constraint?)

What to change to? (What should we do with the constraint?)

How to cause the change? (How do we implement change?)

The first change we made was the reconfiguring of the manufacturing process. Instead of a string of 17 disconnected steps, the consultants drafted a single integrated system with the same 17 steps.

The second change was to get rid of all the unused inventory taking up space reminding everyone about how the former system worked.

The third change was to cross-train everyone on the manufacturing floor to be able to function in every station.

And, the fourth change was to only make socks for actual orders.

It all seemed so simple. As outsiders, the simplicity of the new system made sense. Once these changes were made the process of making socks went from six weeks down to six days.

Simulation as Unconscious Cultural Practices

Yet when you have created a simulation-like environment that is immune to reality, this is what happens. You refuse to believe what everyone else can easily see. It is sort of like the old folk tale of the Emperor’s New Clothes. It is about the power of cognitive dissonance and confirmation bias to avoid facing reality. The current obsession of politicians and social media companies to root out disinformation is exactly this pattern of behavior. They are not interested in clarifying reality. No. They want to continue to live in their simulated reality, no matter how close it brings society to collapse. This is the mindset that had grown in this company.

During the 1990s, the place of values in business had a renaissance. Much of it was the product of Jim Collins and Jerry Porras’s book, Built To Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies.*** The one thing that stuck with me all these years is the importance of having a core ideology.

Core Ideology = Core Values + Purpose

Core Values = The organization’s essential and enduring tenets – a small set of general guiding principles; not to be confused with specific cultural or operating practices; not to be compromised for financial or short-term expediency.

Purpose = The organization’s fundamental reasons for existence beyond just making money – a perpetual guiding star on the horizon; not to be confused with specific goals or business strategies.

The problem that Collins and Porras identify is the one that the hosiery mill had, and many of my clients have had. Cultural practices are the result of the activities associated with “the persistent, residual culture of values.” This becomes the culture of the organization. It can be healthy or illusory. When values lose their value, cultural practices become hardened and entrenched as “the way we have always done things.” This is the mindset of the Simulation. It is a denial of reality.

Collins and Porras recommend that companies Preserve the Core and Stimulate Progress. I like to think that the values and purpose of an organization are the foundation for everything else. Let values lose their vitality, and the foundation fails. This is what was happening at the hosiery mill. Whatever values the founder had at the company’s inception had long ago been replaced with operating practices that were leading the company down the road to closure.

Prior to our intervention, I interviewed the management team. I had thirty minutes with each one of them. I wanted to understand how they perceived the situation and their role in the process. Twenty-five minutes into my time with the sales and marketing director we were still talking about him trying to sell a piece of farmland that he owned. The rest of the team apart from the nephew who ran the manufacturing process were equally detached from reality.

At that time, the thought crossed my mind, how can this kind of thinking be happening? Are they so programmed by habit and not thinking to be unable to change at all? It is one of those patterns of behavior that I will address in another essay in this series.

Each Constraint, A Link in a Chain

It is important to understand that every organization operates as a system. The larger the company the easier it is to lose touch with reality and begin to think that everything is fine. The effect of our change proposal was to shorten the manufacturing timeframe from six weeks to six days. Now, if we were there to transform the whole operation, we would have moved to the next constraint. But we didn’t.

Once the manufacturing process was fixed, the problems at the company left the building and went into the marketplace. The company was dependent upon an outdated sales and order approach that basically required constant sales conversion.

The goal of our project was to fix the manufacturing process. Our failure was to not address the larger issue of what is the goal of their company. We were already using the Goldratt Theory of Constraints system. We should have moved to the largest constraint that they had.

William Dettmer in his book, Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints: A Systems Approach To Continuous Improvement, describes Goldratt’s perspective of seeing systems as chains.

“Goldratt likens systems to chains or networks of chains. … (the) goal is to transmit force from one end to the other. If you accept the idea that all systems are constrained in some way, how many constraints does this chain have?” **

The next constraint was their perception of the business. They saw themselves solely as a sock manufacturer. Their goal was to make socks. Their core ideology was the next weak link in the chain. The problem is that their perception had fashioned a simulation mindset to ignore the changes that were happening in business and specifically with manufacturers.

What they did not realize was that the information age had radically altered their business purpose. They needed a change of perception about who they were as a business. When you live in a Simulation, you can only see yourself as the Simulation defines you. If they lived in the Real-world, they would have understood that their clients, principally a large West Coast department store chain, not only needed socks to sell but also they needed management of the sock inventory at each store. They should have seen that they needed to reinvent themselves in order to save the company.

Unfortunately, the changes that were made with this project were too little too late. Eighteen months after the completion of the changes to the manufacturing process, the company closed.

Impact is Reality

This project coming at an early stage in my consulting career helped me to see patterns of behavior that are the real problems that leaders don’t want to face. In a general sense, there are people who run their businesses but do not know how to lead their businesses. Thinking that leadership of the business is more a creating a perception of leadership than leading. The problem is not understanding leading.

The inability to see that you are trapped in a simulated reality provides the wrong feedback. It keeps confirming that you keep doing the things you’ve always done. You keep reading the right books, hiring the right consultants, believing in the right ideas, and supporting the right people, and yet, things are not improving. They are actually getting worse.

This is why I came to focus on creating impact. Impact is a change that makes a difference that matters. As a speaker, my goal is not to give a great speech. My goal is to move someone in the room to change their life. I want to see someone “take personal initiative to create an impact that makes a difference that matters.” As a writer, I’m not primarily interested in how many people open the email. I am interested if what I wrote changed someone’s perception. As a consultant, I wanted to solve problems, but I found leaders didn’t want to solve the highest leveraged problem. They wanted to do something that made everyone feel good. Therefore, sustain the illusion of the Simulation.

For the hosiery mill, how should they have identified what impact looks like? It is a tough question. It is a tough one because most companies are not externally focused. They are internally focused on the measures that are the easiest to produce.

What is the impact that you want from your life? From your work? For your family?

It is dependent upon what your values are and how those values define your purpose. See how focusing on the impact of values and the impact of your purpose, the impact of your relationships, and the impact of your workforce, you force out of the dull-headedness of the Simulation in order to discover a genuine brightness and energy for what you are going to do every day.

This is the beginning of a new series on Leadership and The Culture of Simulation. If you have not read the previous series, Reality and the Culture of Simulation here are links to the five essays, and to the original one that I wrote in 2013, The Spectacle of the Real.

Part Two

Executing a Vision for Impact as a Shared Experience in Leadership

Observing Patterns of Behavior

You can learn a lot by watching and listening. It is more important than being prepared to speak when someone takes a breath. It is really the only way you can know what the actual needs of a group are. I have had the privilege of working for organizational leaders who by watching them helped me clarify and validate the patterns of behavior that led to the creation of my Circle of Impact model of leadership.

The model is intended to not only help people discover reality but to do so together. For only as a team of shared purpose based upon mutual respect and trust can an organization today weather the perfect storm of collapse that we are facing.

Later today, I go to celebrate one of those leaders who is retiring. He is my model of what a leader of impact is like.

Five Leadership Behaviors

The following is an excerpt from my short book, Seeing Below The Surface of Things: The Brokenness of the Modern Organization. These behaviors help leaders create a culture of Simulation that makes it difficult to see what reality is.

There is the behavior of hubris. In effect, we are better than our competitors, and will always be so. This type of arrogance blinds an organization to its weaknesses and fragility. Sometimes the hubris is very open, and other times quiet and hidden. In both ways, there is a belief that necessary change only comes from the person in control.

A second type of behavior is cluelessness. Don’t laugh. It is more widespread than hubris. It is marked by a lack of awareness. The source of cluelessness is rarely clear. I only know that many leaders lack self-awareness. They are unaware of their own contributions to the problems of their organizations. …

A third type of behavior is the parallel mindsets of idealism and defeatism. A blind belief that the organization will always succeed or will always fail creates vulnerability … Denial of reality is a huge obstacle to overcome when a key to an organization’s future is determined by how well they can fix the problems they face.

A fourth behavior is an obsessive attention to detail. The result is the familiar practice of leaders’ micromanaging every facet of the organization’s function. Perspective is lost through this behavior. …

A fifth behavior is the helper / facilitator. This behavior is similar to the micromanager. Instead of focusing on detail, it is focusing on helping staff do their job. An attention to performance in a positive sense can become problematic when the attention becomes a distraction. The hidden motivation for this behavior is, on the one hand, an inability to trust the person to be responsible for their job, and on the other, the need of the leader for constant validation that their contribution is valuable.

Hubris, cluelessness, idealism, defeatism, obsessive attention to detail, and the helper/facilitator are signals that you or the leader of your organization are not fully rooted in reality. What would a reconfiguration of these traits look like where the organization has a firm grasp on reality? The list could be:

Humility instead of Hubris

Self-awareness instead Cluelessness

Positive Resilience instead idealism or defeatism

Clear priorities instead obsessive attention to detail

Leadership Facilitator instead of helper/facilitator

In our world, we labor under the illusion of leadership greatness. Wars, pandemics, economic collapse, and social unrest are the hallmarks of the culture of leadership simulation. The same illusions of grandeur that propelled the Gang of Five to highjack the presentation are the same reason that many leaders cannot accept responsibility for the crises that come under their leadership.

What then does leadership rooted in reality look like? Here’s the story of the man who I will honor at his retirement later today.

Leading with Vision

Tom Campbell is the retiring president of the Black Mountain Home for Children, Youth and Families in Black Mountain, NC. I met Tom during the selection process for the next president of the home seventeen years ago. Our family volunteered at the home. We have a long-term financial commitment to the home. And I was serving the board as a consultant in their presidential search when Tom was hired.

Tom stood out as a person with vision. At that point in time, the home may have had 20 children under its care. Tonight, they will bed down around 90 children living in family homes on the campus. Each home has two sets of live-in parents who rotate throughout the month. At sixteen, the youth move into a transitional living home, preparing for the time when they turn eighteen and are now considered on their own.

During these seventeen years, the program has grown, the campus has grown, the staff has grown, and the impact within the community of organizations that care for children in need across our state and nation has grown. Every aspect of that vision is specific. Every aspect is tied in some way to the impact that it will have upon a child.

Executing the Vision

A vision is only as good as its execution. Tom has been relentless in building partnerships with people, churches, and organizations that serve to advance the home and the wider childcare community. His vision is practical. He sees what needs to happen and finds ways to make it so.

Everything operates within a concept called Continuum of Care*. This platform of values is the measure applied to every decision. The reality is that none of these children come to the home with an investment portfolio or a college fund. When they turn 18 years of age, they are on their own. But the Continuum of Care means that the home had to provide a way for these young, emerging adults to find a way to be able to go to college. As a result, an apartment village was created for the youth where they can live while continuing their education.

Tom’s Leadership Qualities

After working in a variety of capacities with Tom and the home over the past two decades, the pattern of behavior that I saw in him was not only visionary with excellence in execution but those qualities listed above.

Humility as seen in graciousness.

Self-awareness in understanding that it is all about the children.

Positive Resilience in addressing the physical, financial, programmatic, social, and regulatory challenges that the home daily faces.

Clear priorities based on what is the impact on the children.

Facilitator of other’s leadership as the team excels in their individual contribution to the home being a standard for children’s homes nationally.

The Measure of Leadership is Impact

The Culture of Simulation that afflicts the philosophy and practice of leadership today has no measures that are externally measureable. Sales numbers don’t measure external impact but internal operational efficiency. When I began in this field 38 years, the conventional understanding was that leadership is a role and a title in an organization. I saw it differently.

Instead, I saw that all leadership begins with personal initiative to create impact that makes a difference that matters. The measure of impact is that of change. A change that makes a difference that matters. In measuring leadership, what changes because of a decision, a vision, or the execution of the vision? What difference are they making? This is the only measure that matters in the context of The Culture of Simulation. It is because it is tangible, externally measurable, and replicable in every person, organization, and community. This is the impact that the members of the Black Mountain Home community seek through our participation and contributions. This is the reality that Tom has led us in creating.

Here is the outcome of the execution of the vision that he described to us seventeen years ago. This vision will continue to unfold as the Black Mountain Home has always been about leadership as a shared responsibility. And will continue to be so long into the future.

* Black Mountain Home for Children, Youth, and Families CONTINUUM OF CARE:

We serve children from birth to college age and beyond, including:

Community-based foster care with an emphasis on children 0-6 years old, including many with special medical needs.

Campus-based residential care for school age children living in family-style homes on our beautiful 90 acre campus.

Transitional living and life skills coaching for teens preparing for independent living.

Independent Living for youth who have earned a high school diploma or GED and are pursuing a additional education, vocational training, or participating in our Apprenticeship Program.

Lifelong Living Program for youth who need continued support in adulthood due to intellectual and developmental disabilities.

SERVICE AREA:

Our primary service area is Western North Carolina; however, our home is open to any child in NC in need of care.

CAMPUS LOCATIONS:

Main Campus located in Black Mountain, NC, including an on site home, Eller House, for specialized foster care.

Whitewater Cove campus located in Pisgah Forest, NC which can meet the needs of up to six children in addition.

Note: Jimmy Harmon who became the President of the Black Moutain Home was a guest on The Eddy Network Podcast. Find our conversation here.

Part Three

Leadership based on the Culture of Simulation is ultimately unsustainable.

Understanding The Culture of Simulation

The Culture of Simulation is the media context of the modern world. Watch YouTube and TikTok videos and you see simulated lives. We know they are simulated because they are both unreal and seductive. They want us to believe that lies and infidelity are not real. That cheating is normal and should be not only ignored but encouraged. Why? Because the purpose of the simulation is to convince us that our own pleasure and significance are more important than any person or social value. Not only that, but they want us to believe that there is no consequence to adopting the Culture of Simulation. This is the culture of leadership that has invaded many institutions in our society.

It is one thing to adopt this culture in our relationships with people. It is another when institutions do this. When institutions do this, they are not interested in the person, but rather in the collective hive mind. It is where everyone thinks the same way. It is a pattern of behavior that you can identify by the similarity of the words and the thoughts that are expressed. People who are not part of that hive mind are treated as a danger to society. It just goes to show the fragility of the Culture of Simulation that afflicts people and institutions today.

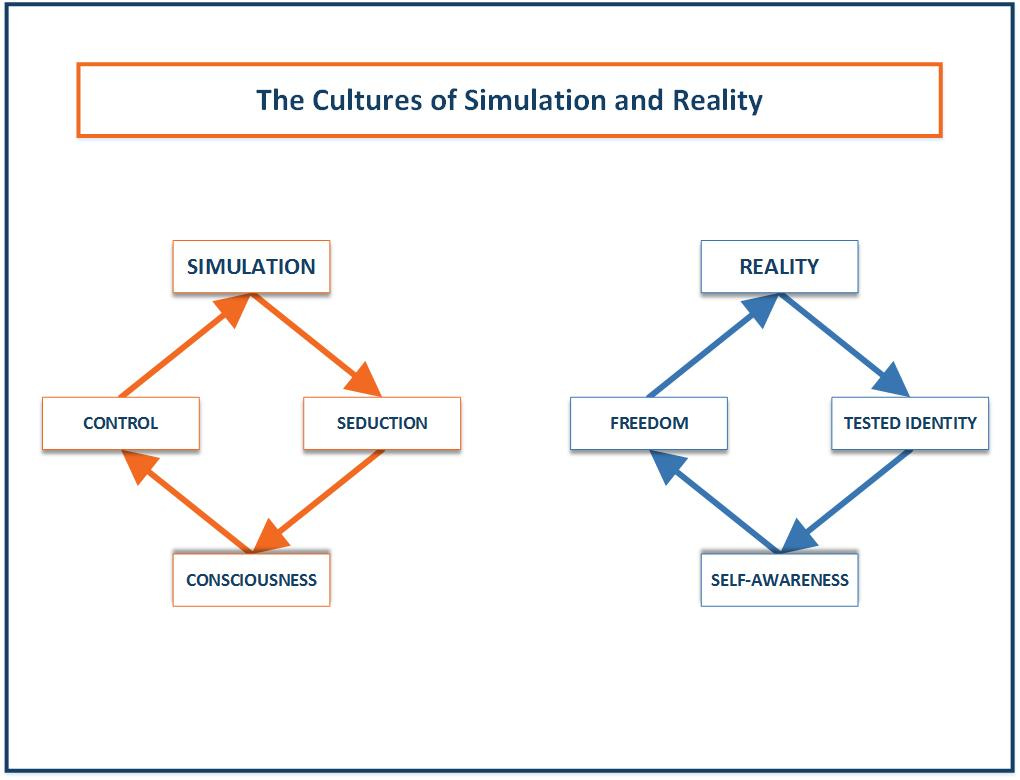

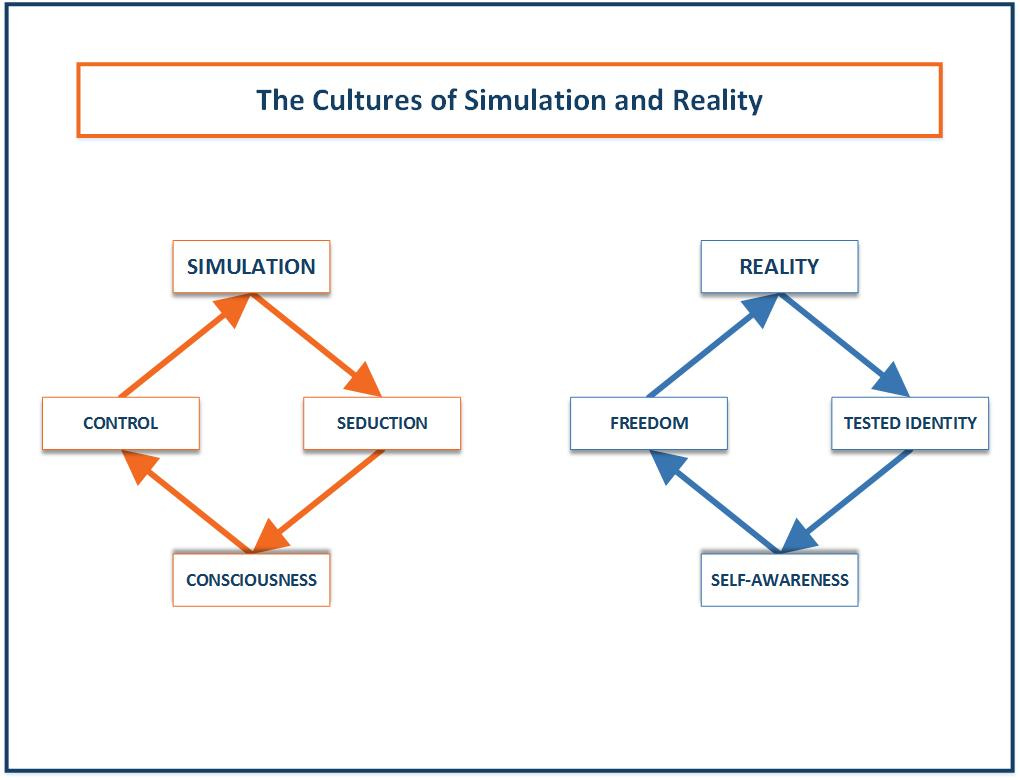

The Culture of Simulation is not benign. It exploits the will of individuals by neutralizing independence of choice. It is a form of mass hypnosis where the seductive power of suggestion programs how people are to respond. You can see it in every communication vehicle. Its purpose is to convince people that compliance is a form of independence. In reality, this culture of seduction has produced a cult-like religious consciousness. It makes it easier to control people.

Leadership and the Concept of the Person

The issue here is fundamental to the nature of leadership. If leaders use seduction as a vehicle for leading, then, whether intentionally or not, they believe that people do not have the capacity to make the right choices. This is how the Culture of Simulation corrupts society and its institutions.

As Harry Frankfurt describes in his essay Freedom of the Will and The Concept of the Person.

“It is my view that one essential difference between persons and other creatures is to be found in the structure of a person’s will. … It seems to be peculiarly characteristic of humans, however, that they are able to form what I shall call “second-order desires”… Because wanting and choosing and being moved to do this or that, men may also want to have (or not to have) certain desires and motives. They are capable of wanting to be different, in their preferences and their purposes, from what they are. Many animals appear to have the capacity for what I shall call “first-order desires” … which are simply desires to do or not to do one thing or another. No animal other than man, however, appears to have the capacity for reflective self-evaluation that is manifested in the formation of second-order desires.”

The Culture of Simulation shows me that human will is not fixed or set at birth, but capable of being nurtured to goodness or evil. This malleability makes it possible to create great works of art, invent life-changing devices, discover new worlds, and build authoritarian regimes to exploit humanity and the planet. It is this capacity for reflective self-evaluation that is both our strength and our weakness. It is not just the freedom to choose but the freedom to choose badly with consequences that are harmful to multitudes of people that we must acknowledge.

My First Notion That Something Was A Miss

Growing up, we had dinner as a family every night. My father was a corporate HR director. He would talk about his day at work. For a period of time, he always had something negative to say about his boss. In retrospect, I am convinced that this is why I did not choose to study business and work in business after college. Ironically, it was the distinctions in the nature of leadership that my father was unknowingly teaching me that ultimately led me into the field of leadership.

When I did begin to study it, I rejected the conception that I found in much of the literature. This concept was that leadership was a role and a title in an organization. The difference can be seen from this quote from Peter Drucker’s early book, Concept of the Corporation.

“No institution can possibly survive if it needs geniuses or supermen to manage it. It must be organized in such a way as to be able to get along under a leadership composed of average human beings. No institution can endure if it is under one-man rule. … these twin dangers, that of depending on the “indispensable “ leader, and the danger of depending on one-man rule, follows first a demand for a constitution under which there is legitimate rule and legitimate and quasi-automatic succession to the rule. … the institution must be able to arouse the loyalty of its members. To produce leaders an institution must have an esprit de corps which induces its members to put the welfare of the institution above their own and to model themselves upon an institutional idea of conduct.”

I believe what we now see is the reverse of Drucker’s perspective. Instead, we see the leadership elite treating their position in society as a carte blanche to do whatever they believe is right.

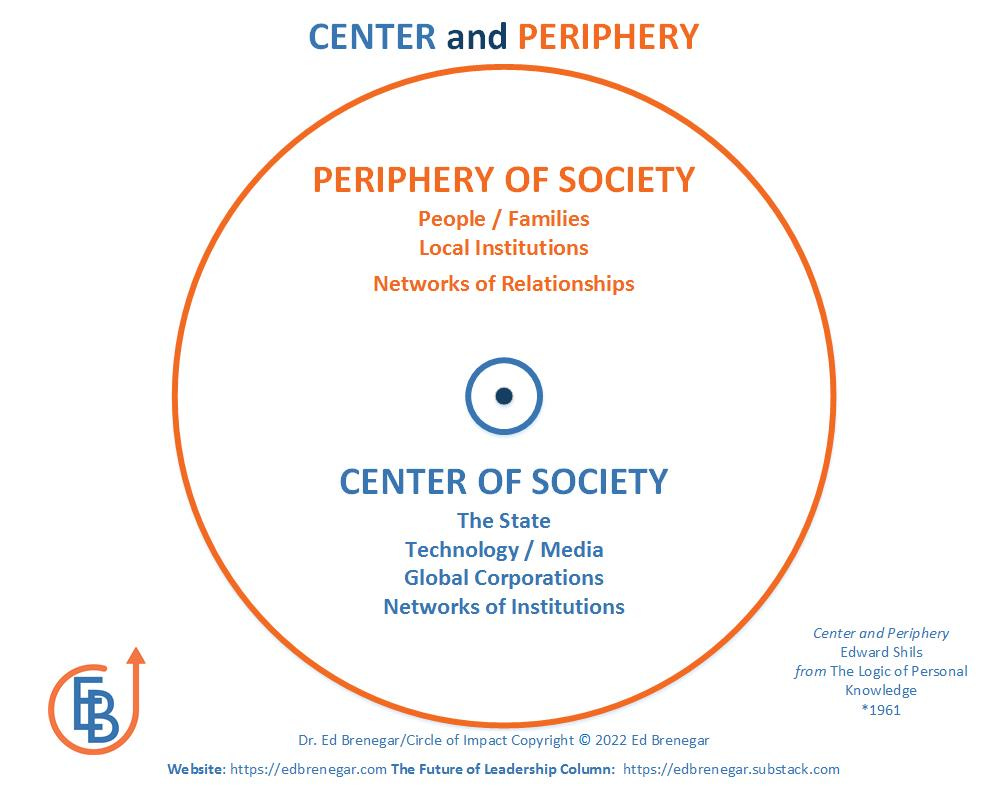

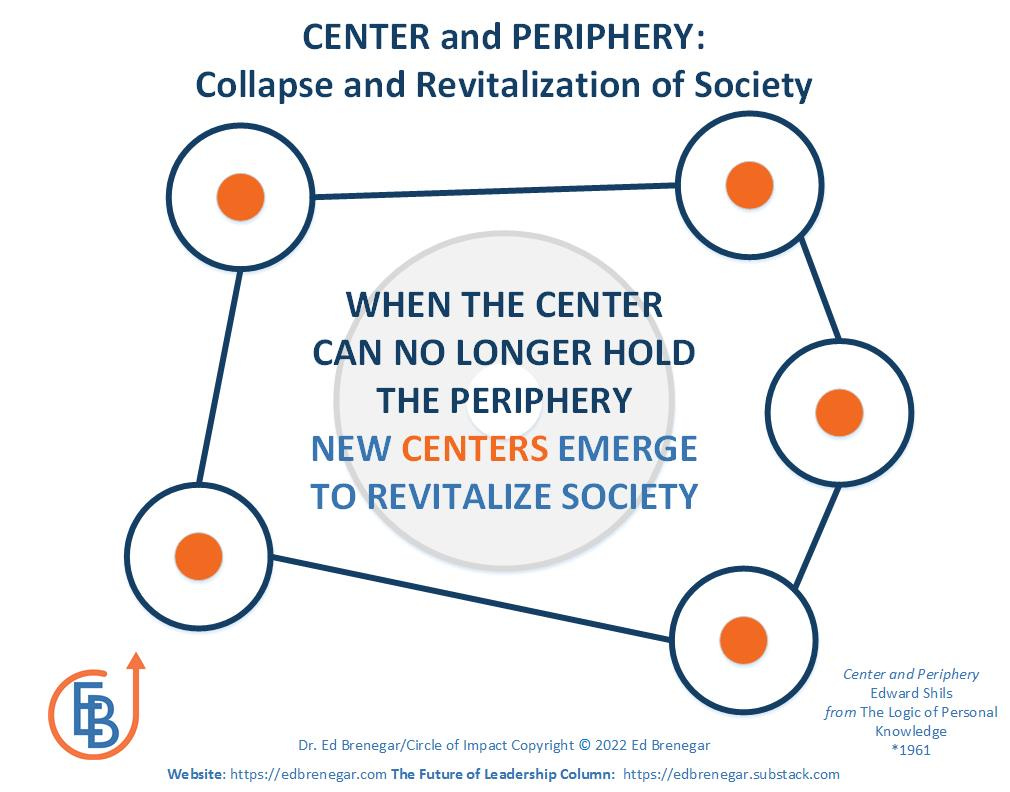

As I wrote in my essay, As The Center Does Not Hold, the Periphery Grows about how society is made up of a center and a periphery.

It is “one of integration and wholeness. The center is like a magnet drawing the periphery into a more connected relationship. In modern society, the Center consists principally of the institutions of the State collaborating with large technology and media companies, global corporations, and other society institutions. At the Center resides the power to dictate how society is ordered and functions.

The Periphery consists of people, families, local institutions, and the personal relationships that we have with people. The power that resides here is personal, not institutional. As a result, the periphery is subject to the power of the center.”

When the Center no longer represents the Periphery, or has chosen to exploit it for its own reasons the following happens.

“If the Center abandons the belief system of society in favor of more subsidiary or contrary beliefs, the Periphery will begin to abandon respect for the Center. … When the Center cannot hold the Periphery, it either dissolves or becomes authoritarian. … When the Center no longer supports the Periphery, the Periphery must turn to its own resources. As a result, multiple smaller Centers form. These new Centers learn to exist more independently of the traditional Center.”

Drucker’s perspective on leadership informed how I began to form my own model of leadership. In particular, I saw that genuine leadership first is the product of personal initiative to create impact. And it builds an institutional culture marked by respect, trust, and mutual accountability between the Center and the Periphery.

Where leaders do the opposite they must foster a culture of simulation in order to disguise what is taking place.

In 2020, I wrote two short books, Seeing Below the Surface of Things and Where Did Trust Go? focused on the brokenness and corruption in organizations. I principally saw the problem as the separation of authority from accountability. Today, we tend to look at the ballot box and the investment markets as to how leaders are held accountable. The problem is that both means of accountability are subject to manipulation. It points to the inadequacy of how we measure leadership and the functioning of society’s institutions. If you are not happy with how the world is functioning today, you now have a way to look at why it is.

What Does Leadership Look Like?

My first reaction to theories of leadership was that it didn’t describe the leaders who I had known over the first three decades of my life. The most influential were in positions of authority, but it was not their institutional authority that produced their leadership impact. Instead, it was the character of their performance in the role that their title defined.

All of this came back to me as I read David Gelles's New York Times article based on his book on Jack Welch, former CEO of General Electric. The promoters of Welch-style leadership point to the financial success of GE under his twenty-year tenure as the validation of his genius. From Gelles’ article,

“David Zaslav, the C.E.O. of Warner Bros. Discovery and a Welch discipline remembered him as a godlike figure. “Jack set the path. He saw the whole world. He was about the whole world … What he created at G.E. became the way companies now operate.”

Was this the concept of leadership that I was reacting to in the mid-1980s? In part, yes, and in other ways no. I say this because our family and later myself were beneficiaries of Welch’s leadership as GE stockholders. However, the short-sightedness of Welch and his style of leadership also left his successors an unsustainable company. From Gelles’ article again.

“Almost immediately after Mr. Welch retired in September 2001 with $417 million serverance package, G.E. went into a tailspin from which it would never recover. His pupils, though, went on to run dozens of other major companies, including Home Depot, Albertson’s, Chrysler, and Boeing. Most of them failed. And in the decades since Mr. Welch assumed power the economy at large has come to resemble his skewed priorities. Wages stagnated and jobs move overseas. C.E.O. pay went stratospheric and buybacks and dividends boomed. Factories closed and companies found ways to pay fewer taxes.”

Of course, few would think of Welch’s leadership as short-sighted. Gelles in his article presents the two sides to Jack Welch’s legacy: In sum, financial success built on an unsustainable platform. Welch is an easy target for criticism. Two decades after his retirement and two years after his death, we can look at his record as less exceptional than it appeared during his time as CEO. This is the nature of the Culture of Simulation. It functions at the moment. Historical reflection tends not to be kind to those who base their leadership style on the Culture of Simulation.

I doubt if Jack Welch ever used the term “simulation” ever. Yet, Welch was not alone in exploiting the world of the 1980s and 1990s. The Culture of Simulation commodifies into different enterprises like politics, the mainstreaming of sexual pornography, the spectacle of professional sports, and the use of social media to build a compliance consciousness in society. This hyper-reality culture has been the vehicle for wealth generation, power acquisition, and the garnering of celebrity status.

The question before us now is two-fold.

Where does this lead us?

What are we to do?

I’ll pick up on these questions in the next column in this series.

References

* Harry Frankfurt, Freedom of the Will and The Concept of the Person

** Peter Drucker, Concept of the Corporation, Transaction Publishers, 1946.

*** Jack Welch – New York Times articles

David Leonhardt, The Jack Welch Effect

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/05/briefing/jack-welch-david-gelles.html

David Gelles, The Man Who Broke Capitalism: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America―and How to Undo His Legacy

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/21/business/jack-welch-ge-ceo-behavior.html

Kurt Anderson, How Jack Welch Revolutionized the American Economy

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/02/books/review/the-man-who-broke-capitalism-david-gelles.html

Part Four

Where does this lead us? What are we to do?

The Culture of Simulation is designed to obscure reality, create confusion, and to concentrate power with a few. All the crises that we face today are all products of this culture of simulation. If you feel isolated, disempowered, and lost in the world, you are beginning to understand the effect that this culture has.

It doesn’t matter what is said about this culture. It is like the mist rising off wet grass. It disappears into the atmosphere of the morning. Words and images are the currency of simulation. Do you automatically believe what you are told? Or do you pause and reflect, is that true? Is that real?

Rights: Lefteris PItarakis

As we live in the context of The Culture of Simulation, we need to ask one another.

Where does this lead us? What are we to do?

First, we need to understand that this culture has a structure to it. Its framework of organization is ideas and methodologies applied through the centralized institutions of business, government, and the media. We receive it as a perception of the world that we are expected to believe without thought. It is as I describe in The Spectacle of the Real. A framework design to capture our attention, suspend our critical faculties, and never let go.

On a recent trip, I had a conversation with a nurse. She remarked that in her city there are two hospital systems. She works at one of them. I asked her about how her hospital handled the coronavirus pandemic. She said that, unlike the other hospital in her city, her hospital did not mandate every staff person to be vaccinated. She had registered a religious exemption that was respectfully accepted.

Later I asked, “How is the social climate at the hospital?” She said the pandemic had been very hard on everyone. The restrictions and protocols that they had to follow did not always allow them to do what they thought was best for their patients. Then she said, on my floor, we understand this, and we have been very supportive of one another.

This framework of simulation is a top-down directed management approach. Forced compliance becomes the culture of the organization. As a result, a greater disconnect between the executive, management, and work levels of the organization happens. In other words, the greater the authoritarian character of management grows, the weaker the organization becomes. Talent and character gravitate towards environments of freedom, not compulsion. This is the framework of simulation as it has developed.

The institutions that adopt a Culture of Simulation model represent “the global force of centralized institutions of governance and finance” from my sTwo Global Forces perspective. Becoming too immersed in The Culture of Simulation, our perception is altered. This is how we are seduced to believe in something that has no direct bearing on our lives. The social and ideological pressure to conform seduces us to believe that there are no options, no alternative belief systems, only compliance, and conformity. Experience it long enough, and a false consciousness takes over one’s personality. At this point, control by the cult of simulation has been accomplished.

The Antidote to the Cult of Simulation

This mass emotional manipulation does not happen only on a global scale. It has takes place in groups of all sizes. Here is a situation that I found myself in where the a group tried to take over the conference agenda.

Enter The Gang of Five

In the late 1990s, I was asked to present a two-hour workshop on community building at an all-day community leadership conference. I was the second presenter of the day. The first was the economic development director of the local Chamber of Commerce. I arrived as he was beginning to speak. What I saw bothered me.

Within the first few minutes of his presentation, members of this group begin to interrupt him. They would ask him questions and make critical statements about the Chamber’s strategy for economic growth. As it turned out, five people, who came to call The Gang of Five, took over the presentation. The young man was not able to present his entire speech. At the end of the hour, he apologized saying he had another commitment, and he left.

For members of a community leadership program to act with such incivility was shocking and disappointing. As for me, the next speaker, I had two choices. Ignore what had happened, and do my planned presentation. Or, I could lead the group of 45 civic leaders through a debriefing process to discover what had happened. In conversation with the organization’s director, we decide to take the latter approach.

Restoring Order and Respect

The first twenty minutes of our debriefing was a heated criticism of the Gang of Five. Seventeen of the forty-five participations spoke during this time. The Gang of Five tried to explain why they felt in necessary to do what they had done. No one was buying their rationale.

At this point, I realized that there were another twenty or so people who had not expressed their opinions. So, I silenced those who had spoken and asked the rest to offer their thoughts. One person said, “If I had known that this is what was going to happen, I would have gone to the office where I have more important work to do.”

After an hour of conversation, I led them through the community-building material that I had prepared. The crisis of that morning had become a perfect context for addressing the conflicting issues that every community has. Instead of the participants leaving at the end of the day with some new ideas. They left as a group that was forced by the actions of a few to work through what it meant for their group to function with trust and healthy communication.

Ironically, the following week, one of the Gang of Five reached out to me asking that I come to help his team. In the end, I spent almost a decade doing various projects with him and the two organizations that he led during that time.

How Reality Presents Itself in the Midst of Simulation

The Culture of Simulation exists wherever there is the manipulation of the perception of what is true. The Gang of Five were adamant that they were right about the Chamber of Commerce’s economic development strategy. They thought that their passionate criticism of the speaker would win the rest of the group over to their side. Even if there were others in the group that shared their opinion, they discovered that the issue was not the most important to them.

Values, when shared, as they were with this group, provide a way to measure whether something is true or not. If there are no shared values or independent thought, only the mechanism of the institution, then it is much easier to be seduced into believing that whatever the institution says is true.

This story also illustrates how a leader has a choice about how their leadership is to be experienced by people. In my role as a workshop leader, I invited the group into a shared discussion about what had happened. We debriefed the experience. In many organizations, the leadership would issue a statement after the fact without any interaction or discussion. When people are not included in the analysis of a negative experience they shared, it is in effect saying, you have nothing to say or contribute. This is how leaders use the Culture of Simulation to create a false culture of inclusion.

The Truth is … Nothing is Hidden

There is an increasing recognition over the past forty or fifty years that business productivity and innovation have been in decline. It is only now beginning to be addressed. If you are a well-paid executive, why risk it? As a result, a Culture of Simulation has grown to hide this reality. We live in an age where everything has exchange value, and real value is only now beginning to be recognized. Nothing is hidden. Everything can be seen. It simply requires the willingness to observe with an open and critical eye. Just as the Wizard in The Wizard of Oz could not hide, so too, none of us can hide behind the veil of Simulation.

What then are we to do?

1. Don’t lie. Be Honest.

If nothing is hidden, it means every lie is out in the open. Why do we lie? The reasons are many. Generally speaking, we lie because we are unsure, we are afraid of being wrong, or we fear making a mistake that we don’t want people to know about. This is just the tip of the iceberg. We lie because it is expedient. We have an initial benefit from lying. We lie to gain leverage over an adversary. We lie to win.

We lose when we lie because we have to remember the original lie, and construct the sequence of lies to back it up. Our time is just a more sophisticated form of the sort that Alexandr Solzhenitsyn described when he was arrested by the Soviet government in 1974.

“There was a time when we dared not rustle a whisper. But now we write and read samizdat and, congregating in the smoking rooms of research institutes, heartily complain to each other of all they are muddling up, of all they are dragging us into! There’s that unnecessary bravado around our ventures into space, against the backdrop of ruin and poverty at home; and the buttressing of distant savage regimes; and the kindling of civil wars; and the ill-thought-out cultivation of Mao Zedong (at our expense to boot)—in the end we’ll be the ones sent out against him, and we’ll have to go, what other option will there be? And they put whomever they want on trial, and brand the healthy as mentally ill—and it is always “they,” while we are—helpless.

We are approaching the brink; already a universal spiritual demise is upon us; a physical one is about to flare up and engulf us and our children, while we continue to smile sheepishly and babble:

‘But what can we do to stop it? We haven’t the strength.’

We have so hopelessly ceded our humanity that for the modest handouts of today we are ready to surrender up all principles, our soul, all the labors of our ancestors, all the prospects of our descendants—anything to avoid disrupting our meager existence. We have lost our strength, our pride, our passion. We do not even fear a common nuclear death, do not fear a third world war (perhaps we’ll hide away in some crevice), but fear only to take a civic stance! We hope only not to stray from the herd, not to set out on our own, and risk suddenly having to make do without the white bread, the hot water heater, a Moscow residency permit.

We have internalized well the lessons drummed into us by the state; we are forever content and comfortable with its premise: we cannot escape the environment, the social conditions; they shape us, “being determines consciousness.” What have we to do with this? We can do nothing.

2. Learn to Work with your Hands

The Culture of Simulation lives in the image on the screen. It is precisely what we were presented with when The Matrix appeared two decades ago. Most of us couldn’t imagine then that our world would resemble it so completely so soon. The problem is that we can know nothing for certain. If we cannot know anything for certain, we cannot know ourselves for certain either.

Accept when we work with our hands, we know something for certain. The bread dough rose. The engine starts. The chair holds up. Each of these is a moment of reality. They cannot be a function of simulation. If you prepare a party for friends, like I did last night, you know immediately whether they like the food that you prepared. Reality is the validation of skill, talent, and expertise.

Matthew Crawford writes about this. He is a guy who earned a Ph.D. in political theory, became the head of a Washington think tank, and then realized that there was an unreality to his work. He wrote an excellent book called Shop Class as Soul Craft: An inquiry into the value of work. In a New York Times article, he wrote,

“Many of us do work that feels more surreal than real. Working in an office, you often find it difficult to see any tangible result from your efforts. What exactly have you accomplished at the end of any given day? Where the chain of cause and effect is opaque and responsibility diffuse, the experience of individual agency can be elusive. “Dilbert,” “The Office” and similar portrayals of cubicle life attest to the dark absurdism with which many Americans have come to view their white-collar jobs.

Is there a more “real” alternative …

When we praise people who do work that is straightforwardly useful, the praise often betrays an assumption that they had no other options. We idealize them as the salt of the earth and emphasize the sacrifice for others their work may entail. Such sacrifice does indeed occur — the hazards faced by a lineman restoring power during a storm come to mind. But what if such work answers as well to a basic human need of the one who does it? I take this to be the suggestion of Marge Piercy’s poem “To Be of Use,” which concludes with the lines “the pitcher longs for water to carry/and a person for work that is real.” Beneath our gratitude for the lineman may rest envy.”

It does not matter what you decide to do with your hands, just that you do it. I do not have hands that lend themselves to precise technical work. I admire people who can fabricate metal into custom automobiles or create beautiful tables and chairs. I marvel at the professional baseball player whose hand-to-eye coordination grants him the skill to hit over .300 and have over 40 home runs. I am amazed at the gardeners who turn the dry ground into gardens of Eden.

What I do is sit here and type. And I can cook and fashion cocktails that bring enjoyment to my friends and guests. Do something with your hands that balances the perception of the world that is forced upon us by the Culture of Simulation.

Do not be Seduced.

Do not casually accept the perceptions presented to you.

Don’t fall prey to the social pressures that turn us from human beings into sub-human automatons. It is a choice that you have and I have to make.

If you want to dig into this let me know, I’m ready to work this through with you.

Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, Live Not By Lies, https://www.solzhenitsyncenter.org/live-not-by-lies

Matthew Crawford, The Case For Working With Your Hands, NYT magazine.

Part Five

What are legitimate measures of leadership?

Leadership and Structural Alignment

The reality is that most businesses are broken. They are out of alignment. This is not a new topic for me. I have been talking and writing about this for over twenty years. This essay extends what I wrote before.*

Leadership culture is a chief reason for this brokenness. By this, I mean that modern leadership cultures of business, politics, sports, and entertainment are seduced by the Culture of Simulation. They define leadership as something other than how one performs in their role.

I have found throughout my consulting career that whoever is this “leader” will be strong in one of the four functions. The selection of that person to fill the role of the leader will be based on the perception that the governance board has about the needs of the organization. The organization will then focus on the function that “the leader” is most proficient in. In large organizations over the past century, that person has primarily been a strong financial leader.

David Leonhardt’s article on David Gelles's book on former General Electric CEO Jack Welch describes this development.

“For decades after World War II, big American companies bent over backward to distribute their profits widely. In General Electric’s 1953 annual report, the company proudly talked about how much it was paying its workers, how its suppliers were benefiting and even how much it paid the government in taxes.

That changed with the ascendance of men like Jack Welch, who took over as chief executive of G.E. in 1981 and ran the company for the next two decades. Under Welch, G.E. unleashed a wave of mass layoffs and factory closures that other companies followed. The trend helped destabilize the American middle class. Profits began flowing not back to workers in the form of higher wages, but to big investors in the form of stock buybacks. And G.E. began doing everything it could to pay as little in taxes as possible. …

Welch transformed G.E. from an industrial company with a loyal employee base into a corporation that made much of its money from its finance division and had a much more transactional relationship with its workers. That served him well during his run as C.E.O., and G.E. did become the most valuable company in the world for a time.

But in the long run, that approach doomed G.E. to failure. The company underinvested in research and development, got hooked on buying other companies to fuel its growth, and its finance division was badly exposed when the financial crisis hit. Things began to unravel almost as soon as Welch retired, and G.E. announced last year it would break itself up.”

The impact of these trends was a fragmenting of the structures of organizations. This diagram shows the transition from a unified structure where the social and organizational structures operated in tandem. Then, possibly fifty to sixty years ago, things began to change. As the executive, managerial, and worker levels became increasingly segregated and isolated from one another. The social structure of “the persistent, residual culture of values” defined the different segments, not the whole company.

With one client of mine, the social culture defined the company, even though the executive leadership followed Welch’s finance orientation. Another client suffered the diminishment of the company’s morale as their executives were also principally focused on the financial state of the company. In many communities, small businesses have been driven out of business because of the predatory character of much larger businesses. The problem is not the financial function itself. It is the over-valuing of finance. Or as Bill George, the former C.E.O. of Medtronic remarked about the impact of Jack Welch,

When product development, customer service, and governance take a back seat to finance, you have a similar misalignment as with structure is emphasized over values and purpose creation and the fostering of an environment for relationships of respect, trust, and mutual accountability.

What is Leadership?

It is not my purpose to sound like some old curmudgeon complaining about the world of leadership. I’m not a complainer. I am only speaking about what I see. What I see is a lot of people who know how to run their organizations, not know how to lead them. This is why it is important to talk about what constitutes legitimate and illegitimate measures of leadership?

We need to begin with an understanding of what leadership is and what it isn’t. The conventional thought throughout my almost 70 years of life is that leaders occupy a role and a title within an organizational structure. In this sense, the only measure of leadership is the internal efficiency of the organization. Is the Profit/Loss report a legitimate measure of leadership. Or, is it, as I believe it is, a measure of managerial ability.

Mohamed Al Zarooni writes.

“Manager and leader are two completely different roles, although we often use the terms interchangeably. Managers are facilitators of their team members’ success. They ensure that their people have everything they need to be productive and successful; that they’re well trained, happy and have minimal roadblocks in their path; that they’re being groomed for the next level; that they are recognized for great performance and coached through their challenges.

Conversely, a leader can be anyone on the team who has a particular talent, who is creatively thinking out of the box and has a great idea, who has experience in a certain aspect of the business or project that can prove useful to the manager and the team. A leader leads based on strengths, not titles.”

He points to Daniel Goleman’s HBR study of middle-managers in 2000 which identified the following types of leaders.

The pacesetting leader

The authoritative leader

The affiliative leader

The coaching leader

The coercive leader

The democratic leader

The problem here is that this is not a holistic understanding of leadership.

Two questions

How do we measure each as a function of organizational leadership?

What is missing?

Look again at the diagram above. The transaction version treats leadership as a role within the structure. It is a limited role. Are there only six types of leaders? This is the wrong way to see leadership.

In the transformational scheme, the organization is a whole entity. It isn’t fragmented into these parts. How often have you had conversations about the silos at work? This is because leadership has been designed to serve the structure of the organization. And it serves best those who benefit the most. I believe there is another way.

Leadership as a Function of Human Performance

I see that “all leadership begins with personal initiative to create impact that makes a difference that matters.” This means that everyone in an organization from the CEO all the way down to the maintenance staff can function in a leadership capacity. If everyone can have a leadership impact, then everyone can be measured for their leadership.

As much as I want to celebrate Mohamed Al Zarooni and Daniel Goleman’s perspectives, it does not really change anything. It doesn’t provide a ground for a legitimate measure of leadership.

Let’s do a little exercise. Ask these questions about the place where you work.

What has changed over the past two years? How are we in transition?

What is the impact that we are having? What is the difference that matters that we create every day?

Who are we impacting? Who is missing from this list?

What opportunities for impact do we have right?

What problems have we created? What obstacles do we face?

These are the Five Questions that Everyone Must Ask. If you and your team were to answer them on a weekly schedule, you will find that your orientation to impact grows. And more importantly, you will know what to do and what you can stop doing.

Impact and The Culture of Simulation

From my observations, most of the measures that we use to define leadership are not the ends of leadership, but rather the means to it. Those means should lead to some change that makes a difference that matters.

What then should be the impact of every worker and who should their leadership be impact.

What is the qualitative difference?

What should be the impact of every middle manager? Who should they be impacting?

What should be the impact of executive in the C-suite? Who should they be impacting?

An organization’s definition of impact reveals the company’s values and purpose. To be absolutely clear, each person in a company should be able to state not only what the values are, but what the impact of those values are to be. This is how a persistent, residual culture of values ultimately defines the impact of the company.

The Culture of Simulation is insidious. What is the impact of the simulation? The means to that impact is seduction into a belief system that fosters, not the freedom of the individual to take personal initiative to create impact, but rather to submit to the controlling interests of those in power.

Through the Culture of Simulation, every CEO, every National President or Prime Minister, every Governor of a State, and every Mayor of a major city is telling us without wanting to that they are responsible for the way the world is.

The impact that you experience in your work and life is the product of their leadership. If you believe that leadership is a role and a title in an organizational structure, then you must believe that the top leaders of every global institution are responsible for the crises that afflict us.

When they do not accept responsibility, when they point their finger toward someone else or some group and blame them for the problems that we face, they are telling us that they have failed as leaders.

As a leader in authority and with responsibility, casting blame on someone else demonstrates is weakness. It erodes the ground for leadership that unifies society to address its crises. The reason the Culture of Simulation exists is to hide the real impact of their leadership which is their greed and lust for power and wealth.

This distinguishes between the people who only know how to run their business and and not lead their business.

To lead is to elevate the capacity of everyone to be a person of impact.

To lead is to accept responsibility.

To lead is act to resolve the problems that we face.

Impact – The Only Legitimate Measure of Leadership

Impact is change. It is a change that makes a difference that matters. You can only know what matters by being clear about your values and purpose for impact.

What is your company’s purpose for impact?

What do you want to change?

The crises that we face on a global scale are not accidents but is the impact of the leaders of the Culture of Simulation.

So, what should you do?

First, embrace reality by asking what is the impact that we are experiencing.

Second, embrace your people, and your network of relationships.

Respect and Trust them.

Train them to be impact leaders.

Equip them to solve problems, communicate better, and innovate how they do their work.

Support and celebrate their personal initiatives.

Create a way to be mutually accountable by being clear about our shared values for impact.

Third, do not dream for a better world instead create impact in the areas that are within your reach right now.

What then is a legitimate measure of leadership? Impact.

It is a change that makes a difference that matters.

Every other measure is just preparation or delay for creating impact.

Note:

* The idea of the brokenness of modern organizations I first developed in my book, Circle of Impact: Taking Personal Initiative To Ignite Change. See Chapter 6 Organizations in Transition.

Almost three years later, I returned to the question of organizational brokenness after a conversation with leaders about government corruption.

My thoughts are captured in two short books, Seeing Below The Surface of Things: The Brokenness of the Modern Organization and Where Did Trust Go? Restoring Authority and Accountability in Organizations.