Social Capital and Mimetic Violence

By creating networks of relationships rich in social capital, we can learn to address our own tendencies towards jealousy and envy as a society.

In my previous post, We Learn Iteratively and Emergently, I wrote about how I learn and the process of relearning in new contexts. The process involves taking one idea, like social capital, and holding it up like a picture in front of the landscape of another idea to see how they interact. This results in a network or web of ideas interconnected together.

In this post, I’m seeking to understand social capital in the social context of an idea of René Girard’s concept of “mimetic desire.” In the world today, I observe that in many ways we are far from the idea of social capital, and much closer to the reality of mimetic conflict. I want to restate how social capital has been understood and then describe Girard’s thoughts.

Social Capital

In my post, The Science of Networks of Relationships, I place the idea of social capital in the context of network theory using ideas like structural holes, the strength of weak ties, and the diffusion of innovations as ways to understand how social capital functions. This view is one view, but not the only one that describes social capital.

James Coleman was the first to describe what is known as social capital. He viewed social capital as similar in content to physical capital and human capital. In this sense, the idea of social capital is a conversation that takes place between sociologists and economists. Coleman writes.

“If we begin with a theory of rational action, in which each actor has control over certain resources and interests in certain resources and events, then social capital constitutes a particular kind of resource available to an actor.

Social capital is defined by its function. It is not a single entity but a variety of different entities, with two elements in common: they all consist of some aspect of social structures, and they facilitate certain actions of actors-whether persons or corporate actors-within the structure. Like other forms of capital, social capital is productive, making possible the achievement of certain ends that in its absence would not be possible”

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu took a more Continental view of social capital. Tristan Claridge describes.

“Bourdieu saw social capital as a property of the individual, rather than the collective, derived primarily from one’s social position and status. Social capital enables a person to exert power on the group or individual who mobilises the resources. … For Bourdieu social capital is irreducibly attached to class and other forms of stratification which in turn are associated with various forms of benefit or advancement. … The key difference between Bourdieu’s conception of social capital and virtually all other approaches is the treatment of power. For Bourdieu, social capital is linked to the reproduction of class, status, and power relations, so it is based on the notion of power over as opposed to power to.”

Here I find social capital being distinguished between classic Marxist and classic Free-Market Capitalist thought. Bourdieu sees social capital functioning in the context of social class, while Coleman and others want to describe it in the economic terms of individuals free to associate and collaborate across the structural holes of social networks.

Mimetic Theory

René Girard began his academic teaching career teaching a course on literature. As he prepared, he realized that most treatments of literature look at what is distinctive of each work. He asked the question, “What links them together?” He discovered that the link was the idea of imitation. Human beings imitate one another as a way of knowing who they are. This idea on imitation led to a theory call mimetic desire. Here Girard describes this unique and complex idea.

“If you survey the literature on imitation, you will quickly discover that acquisition and appropriation are never included among the modes of behavior that are likely to be imitated. If acquisition and appropriation were included, imitation as a social phenomenon would turn out to be more problematic than it appears, and above all conflictual. If the appropriative gesture of an individual named A is rooted in the imitation of an individual named B, it means that A and B must reach together for one and the same object. They become rivals for that object. If the tendency to imitate appropriation is present on both sides, imitative rivalry must tend to become reciprocal; it must be subject to the back and forth reinforcement that communication theorists call a positive feedback. In other words, the individual who first acts as a model will experience an increase in his own appropriative urge when he finds himself thwarted by his imitator. And reciprocally. Each becomes the imitator of his own imitator and the model of his own model. Each tries to push aside the obstacle that the other places in his path. Violence is generated by this process; or rather violence is the process itself when two or more partners try to prevent one another from appropriating the object they all desire through physical or other means. Under the influence of the judicial viewpoint and of our own psychological impulses, we always look for some original violence or at least for well defined acts of violence that would be separate from nonviolent behavior. We want to distinguish the culprit from the innocent and, as a result, we substitute discontinuities and differences for the continuities and reciprocities of the mimetic escalation.”

René Girard believes that these mimetic conflicts become ritualized into a religious form. The ritual requires a sacrifice to appease the mimetic community. Someone then must be singled out to be sacrificed. This person or group becomes the scapegoat. The death or exile of the scapegoat returns peace to the community.

To better understand this complex set of ideas related to mimetic violence and the Scapegoat of René Girard, I recommend listening to David Cayley’s excellent series of interviews and commentary with René Girard. (See note at end of this post for a complete listing of the series with links.)

Social Capital in the Context of Mimetic Rivalry

Social capital theory believes that people want to do good and to connect with others to create good things for their community. Mimetic theory says that we are all imitators and when this imitation becomes competitive it produces conflict and violence. I believe both of these ideas represent reality in human society. People will do the right thing until it appears it will grant their competitor or antagonist an advantage over them.

If we combine Bourdieu’s version of social capital theory with Girardian Mimetic theory, I believe it explains why the emerging division in the world is between the Global institutions and the Local networks of relationships. The great conflicts today are all generated by those in the elite strata of society. The protests today are responses to the elite’s actions. They are ways of seeing how the mimetic rivalry of the elite spreads out to touch everyone in the world.

These elites are often referred to as the One-Percent. They all know each other. They went to the same schools. Live in the same communities. They hold the same beliefs about the world and the future. In many respects, they have found themselves all achieving the same thing at the same time. In social capital theory, they represent a close network of strong ties. They cannot settle for sharing their wealth and power. They individually believe that they are the ones who should determine the course of human history. Their wealth, position in society, and their vision for the future grant them this belief in themselves. These are not new beliefs, but old ones. As a result, the highest educated, the most politically connected, and those who own and control the largest, most valuable global corporations in the world including all forms of the media are trapped in a mimetic conflict.

I am convinced that in their pursuit of control, they will destroy the very institutions that have provided them their wealth and privilege. This is not really a political crisis, though politics is a stage for their violence, it is a spiritual crisis, a crisis of the human soul. When you cannot resolve the inner conflict with your imitative other, you are unable to resolve the inner conflict with yourself.

As I understand it, mimetic conflict is a narcissistic weakness that makes the social capital difficult to create. If we cannot share, collaborate, or live in peace, we do not know who we are or what we have to offer the world.

Two Global Forces of Conflict

In our society today, we can identify mimetic rivalry at every turn. We especially see it in the political sphere where social ideology is the playing field of this rivalry. Activists of the Left and the Right want the same thing. They want to control the ideological battleground that ultimately leads to control of political institutions and the wealth that governments generate for their supporters. This is one of those mimetic centers of conflict.

The second center of conflict is between the political/economic ideologies of Socialism and Capitalism. My perspective is that they represent two sides of the same coin. The distinction is mimetic. We have one form today. State-sponsored capitalism has a Western look and an Eastern look. Both use the structure of the state to guide economic growth. As a result, there is a mimetic conflict between the East and the West.

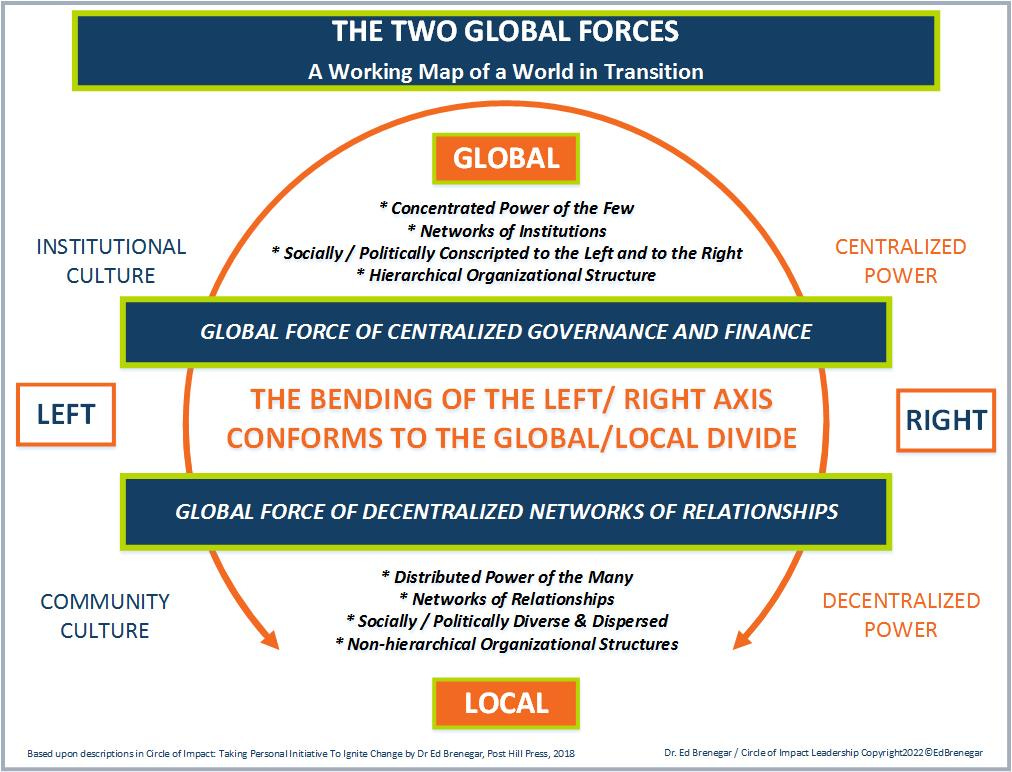

This perspective is part of my Two Global Forces framework that I first wrote about in my book, Circle of Impact: Taking Personal Initiative To Ignite Change. I wrote a series called Two Global Forces in Conflict, here, here, and here. The transition that I believe we are witnessing today is not between Left and Right who want the same thing, yet are in mimetic conflict over who wins control, but between the Global and the Local.

You can see this distinction mapped out in this diagram. As the divide between Global and Local grew more pronounced in my awareness, the more I realized that there are people of the Left and the Right in Local communities who have far more in common than they do with their party members at the national and Global level.

In my estimation, we are moving towards greater and greater mimetic violence. The social capital of networks of relationships are our hope for surviving this violence. I believe it is important to always took away from that which demands your constant attention. If you look, you will find examples of social capital within your local community. Invest yourself there in direct service to people and institutions. When we do that, we can recognize that mimetic violence is not a given for society, but an option to be addressed and resisted.

David Cayley with Rene Girard

Main page

http://www.davidcayley.com/podcasts/category/Ren%C3%A9+Girard

The Scapegoat

Segment 1:

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/the-scapegoat-the-ideas-of-ren%C3%A9-girard-part-1-1.3474195

Segment 2:

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/the-scapegoat-the-ideas-of-ren%C3%A9-girard-part-2-1.3474463

Segment 3:

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/the-scapegoat-the-ideas-of-ren%C3%A9-girard-part-3-1.3483382

Segment 4:

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/the-scapegoat-the-ideas-of-ren%C3%A9-girard-part-4-1.3483817

Segment 5:

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/the-scapegoat-the-ideas-of-ren%C3%A9-girard-part-5-1.3494516

Transcript:

http://www.davidcayley.com/s/Scapegoat.PDF

Violence and The Sacred

Segment 1:

https://www.davidcayley.com/podcasts/2015/3/14/on-violence-and-religion

Segment 2:

https://www.davidcayley.com/podcasts/2015/3/14/on-violence-and-religion-part-two